Friday, September 12, 1986.

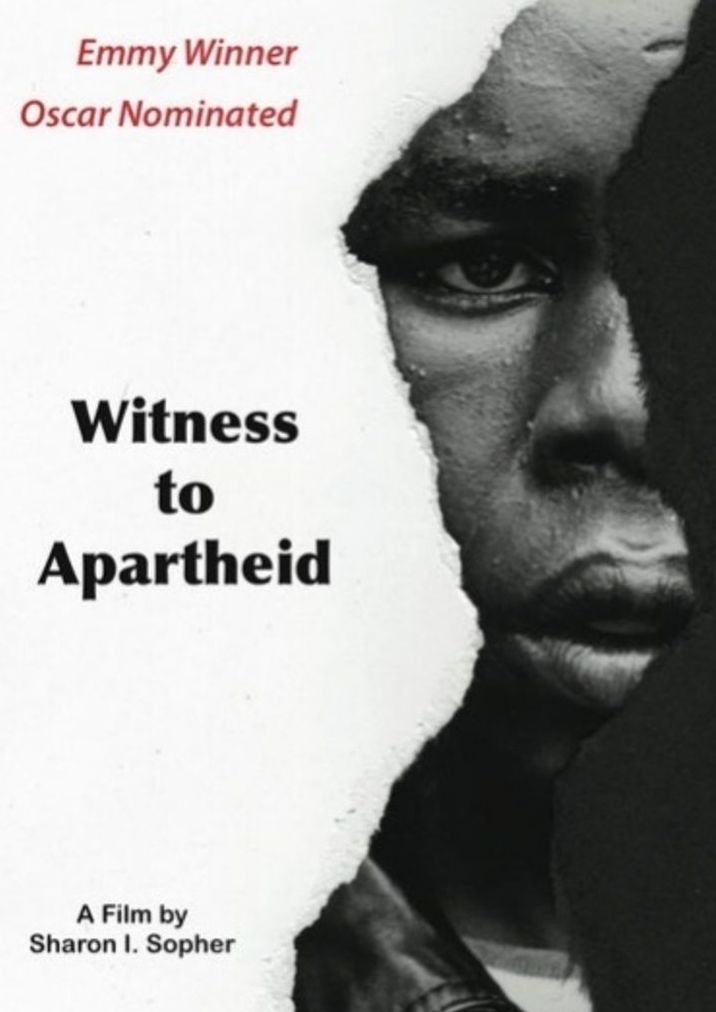

WITNESS TO APARTHEID. Co-written by Peter Kinoy. Co-written, produced and directed by Sharon I. Sopher. Running time: 56 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: some disturbing scenes.

WINNIE AND NELSON MANDELA. Written, produced and directed by Peter Davis. Running time: 57 minutes. Mature entertainment with no B.C. Classifier’s warning.

THE PAGES ARE YELLOWING. A Penguin paperback, Elliott and Summerskill’s A Dictionary of Politics was first published in 1957, a time of intense interest in both domestic and international affairs in Great Britain.

"Apartheid," reads the entry on Page 19. "Afrikaans word (literally ‘apart-hood’) meaning racial segregation as practiced by the National Party which came to power in South Africa in 1948.

“There had been racial segregation in South Africa from the mid-seventeenth century when European colonization began, but the National Party in particular introduced a series of measures affecting nearly all aspects of the life of the non-whites, who form 79 per cent of the population.

“The policy involves racial purity and and white paramountcy (baaskap) . . .”

The policies of the ruling National Party (described further on as “a right-wing, semi-Fascist group) appalled liberal Britons.

The Penguin Dictionary appeared the year after Father Trevor Huddleston’s conscience-stirring Naught for Your Comfort, an Anglican priest’s account of his 12-year ministry in the black slums of Johannesburg. It was a time when human rights were becoming a global issue.

Thirty years ago [1956], movements for civil and political rights were organizing in both the United States and South Africa. “The fundamental difference" recalls Bishop (now Archbishop) Desmond Tutu, in documentary filmmaker Sharon Sopher's Witness to Apartheid, was that “the law in the United States was on the side of those campaigning.”

In South Africa, a movement with a Gandhian commitment to non-violence discovered that the government lacked "that minimum moral level” that gives acts of conscience and peaceful protest their power in civilized societies. For 30 years, Afrikaners have turned a blind eye to the social injustices perpetrated for their comfort by a violence-prone administration dedicated to "apart-hood."

Today [1986], headlines indicate that the situation in that troubled state can only worsen. Taking us behind the headlines are a pair of uncompromising documentaries produced by award-winning television journalists from the U.S. and Britain.

Using traditional documentary techniques — narration and archival footage — director Peter Davis's Nelson and Winnie Mandela tells the story of South Africa's best-known black activists. Davis's picture is built around an extensive, often moving interview with the “banned” Winnie Mandela that had to be filmed in secret and smuggled out of the country.

Using a more TV-news-special approach is Witness to Apartheid, director Sopher's hard-hitting look at the war that the government currently is waging upon its own people. A former NBC news producer, Sopher focuses on the plight of South Africa's black children, a generation growing up without hope in an atmosphere of permanent repression and official brutality.

"We've got a new breed of children,” says Bishop Tutu. “They believe that they're going to die, many of them, or most of them. And the frightening thing is that they actually don't care.

“In their view, the only language the white government understands is violence.”

Not for your comfort are these glimpses of a nation governed by men seemingly hell-bent for an avoidable race war. Offered for your understanding, this documentary double feature is booked for a week-long run at the Ridge Theatre.

Producer-director Peter Davis will appear in person at the 7:30 screening tonight [1973] to introduce the films and discuss his own experiences producing a clandestine movie in an authoritarian state. Proceeds from the premiere showing will go to OXFAM projects in South Africa.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1986. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: An Oscar winner for his 1975 documentary feature Hearts and Minds, Peter Davis returned to the subject of South Africa following the 1990 release of Nelson Mandela from prison. In 1993, he examined how the popular culture shaped the narrative in his feature-length In Darkest Hollywood: Cinema and Apartheid, then focused on the career of Nelson Mandela: Prisoner to President (1994). From the beginning, he made it clear that Winnie and Nelson were their nation’s power couple.

The point was not lost on Guardian foreign correspondent David Beresford, whose reporting was central to that newspaper’s April 2 obituary for Winnie Madikizela-Mandela. It noted that “there was somehow an inevitability about Winnie and Nelson meeting, setting in motion one of history’s great and yet tragic love stories.” Inevitable, because they both shared an intense dedication to the black African freedom struggle. Tragic, because their historical circumstances tore them apart.

Nineteen eighty-six was 24th year of Nelson's 27 years in prison. During his confinement he was a symbol of the cause, regarded as a secular saint. Three years after his release, apartheid ended, and he received the 1993 Nobel Peace Prize for his part in brokering the deal. A year later, he was elected the first president of the new South Africa.

By 1986, Winnie was the battered veteran of the ground fighting. As the only well-known African National Congress member not locked away, she faced years of banishment and physical abuse. There were allegations of personal impropriety and sex scandals. And yet she persisted. Following Nelson’s release there was a triumphant reunion, then more scandal. Their differences became irreconcilable, and they divorced in 1996. When he died in 2013 at the age of 95, he was revered as “Father of the Nation.”

Winnie, whose story is considerably more complex, continued to serve her party and country in various ways. When she died this month at the age of 81, there were those who considered her the “Mother of the Nation” and “Queen of Africa” (the image that director Darrell Roodt presented in his 2011 Canada-South Africa co-production Winnie Mandela, shot in Cape Town, Johannesburg and Montreal). Others focused on the darker moments in her life. Although history’s verdict on Nelson is unlikely to change, its assessment of Winnie remains a work in progress.