Friday, July 17, 1975.

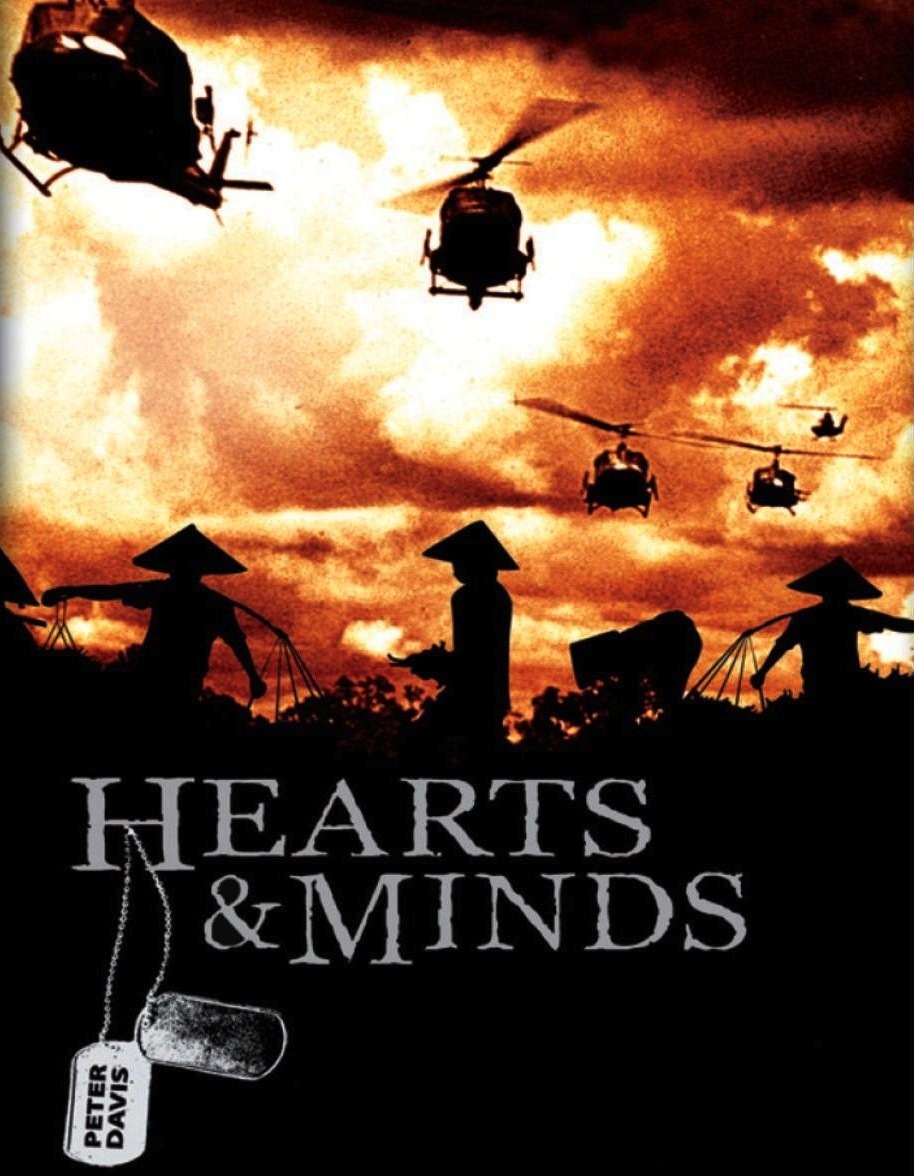

HEARTS AND MINDS. Documentary examination of the U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia. Conceived and directed by Peter Davis. Running time: 112 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: many real scenes of horror from the Vietnam war.

JOHN GRIERSON HAD NO illusions about the purpose of documentary. To the man who fathered the form and founded Canada's National Film Board, motion pictures were less an art form than a social force. Documentaries were supposed to shape public opinion.

American director Peter Davis is a proper Griersonian. He makes no pretence to objectivity. His movie, Hearts and Minds, the first English language item in this year's [1975] Varsity Festival of International Films, is designed to grab hold of its audience and convince it that Vietnam, the longest war in U.S. history, was not only the nation's biggest mistake, but its greatest shame.

Davis is a filmmaker who is not afraid of big targets. In 1971, he took on the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff with his TV special, The Selling of the Pentagon, a compelling examination of how pro-military attitudes are "sold" to the American people.

Although it drew fire from high places, Davis's network, CBS, stood behind him. Exactly one month after its original broadcast, the Pentagon special was aired a second time. Included was a personal statement from the president of CBS News, voicing his approval.

Though not made for TV, the current Davis film managed to create its own small-screen uproar on this year's Academy Awards broadcast. The sparks began flying moments after Hearts and Minds was named best documentary feature of 1974.

As part of his acceptance speech, producer Bert Schneider read a telegram from the Provisional Revolutionary Government of Vietman, otherwise known as the Viet Cong. Backstage, battlefield comedian Bob Hope was outraged.

Later in the show, at Hope's insistence, his stony-faced co-host Frank Sinatra read a stiffly worded disclaimer, a performance that drew more attention to the incident than it would have received otherwise.

Vietnam remains a highly charged emotional issue. It is this still-potent charge that gives Hearts and Minds its extraordinary impact.

A master of his medium, Davis has packed his film with raw emotion, all of it used to further his purpose. From it, he shapes a picture of the war and poses the last remaining, indeed the last important, question: Why?

His film consists entirely of news footage, public statements, interviews and selected entertainment film clips (including a few moments of Bob Hope from 1962's The Road to Hong Kong). There is no narration.

There is, however, a very careful structure.

First, there is an introduction to the historical background. The decision makers — Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Nixon and Johnson — make their appearances. "I do not expect that there is going to be a Communist victory in Indochina," intones the late Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles.

We see the war become an environment, and a perennial political issue. Two former bomber pilots are introduced. Lt. George Coker, a former prisoner of war, is given a red-carpet welcome home. Lt. Jerry Holter, who apparently mustered out without fanfare, is interviewed on his front porch.

Both men saw themselves as technicians "doing a job." There was some exhilaration in flying under fire. We are shown some footage of "the job," and some victims of the war are interviewed. Against this juxtaposition of images, and conflict of emotions, the political debate continues.

Mui Duc Giang, a Vietnamese coffin builder with a low opinion of both his own government and the Americans, is seen doing his job, mass-producing child-sized caskets from rough planking. Next, we hear from General George S. Patton IV. "They're a bloody good bunch of killers," he says of his soldiers.

A candid Saigon war profiteer, Nguyen Ngoc-Linh, is interviewed. The film cuts from his discussion of profits to scenes of crippled Americans learning how to use their prosthetic limbs.

Davis shows us how the Americans became victims of their own war, and when the decision makers return to the screen, they sound like fools.

Davis lets Capt. Randy Floyd, an ex-bomber pilot with 98 missions, a man deeply troubled by his part in the slaughter, deliver the film's ultimate message. "Do you think we learned anything from all this?" his interviewer asks.

"I think we're trying not to," Floyd answers sadly.

In many ways Hearts and Minds is an example of retrospective morality. A decade too late to save the U.S. from its Indochina folly, it sets itself an even more difficult task. It tries to make its audience think about things that most of us would rather forget.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1975. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Although the corporate consolidation of the motion picture business began in the 1960s, the times themselves were turbulent enough to guarantee a certain level of freedom to the creative artists who actually made the movies. Thus, a pro-war actor-director, such as John Wayne, could find funding for a pro-Vietnam war feature (1968's The Green Berets), while anti-war director Robert Altman could make M*A*S*H (1970). Though we currently live in times every bit as turbulent, corporate Hollywood is considerably calmer. Because every major studio is part of some larger media conglomerate (and because of the astronomical costs of entertainment film production), little reaches the big theatre screen that seriously challenges the official narratives endorsed by Joe Haldeman's "people who are in positions of power."

Which leaves us with the documentary: a marginal, shoestring-budget genre that attracts investigative newsmen — director Peter Davis worked for both the New York Times and CBS News before making Hearts and Minds — who share a passion for the story behind the story. In recent years, feature filmmakers such as Platoon director Oliver Stone have embraced the non-fiction film form to tell the stories that wouldn't otherwise come to light. Events such as Vancouver's annual DOXA Documentary Film Festival have emerged to ensure that such films find an audience. Documentary has become more important than ever because real remembrance requires more than a day.