Tuesday, October 12, 1976

THE FRONT. Written by Walter Bernstein. Music by Dave Grusin. Produced and directed by Martin Ritt. Running time: 95 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: occasional coarse language.

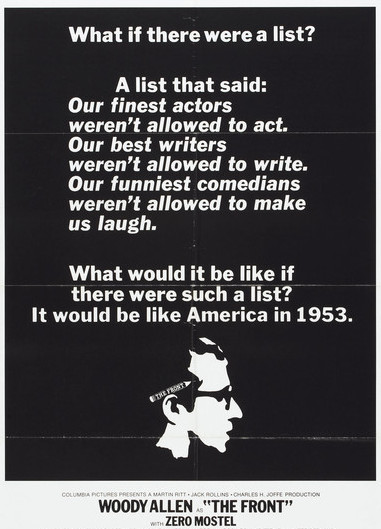

THE ADS ARE BLACK, creating a mood reminiscent of The Exorcist or Judgment at Nuremberg. The message, in white block letters, is sombre and serious.

"What if there were a list?

"A list that said:

“Our finest actors weren't allowed to act. Our best writers weren't allowed to write. Our funniest comedians weren't allowed to make us laugh.

"What would it be like if there were such a list?

“It would be like America in 1953."

The Front is being sold as a sincere, significant drama on the horrors of blacklisting. Many of the people involved in the project, including producer-director Martin Ritt and actors Zero Mostel and Herschel Bernardi, were blacklisted in the early 1950s.

It's impossible not to sympathize with their suffering.

Unfortunately, it's also impossible to have much sympathy for their movie. Like a good friend who drinks too much and vomits all over the living room rug, it is an embarrassment.

Its heart may be in the right place, but its guts are malfunctioning.

Consider that ad line. It implies that the injustices of the blacklist were reserved for the finest actors, best writers and funniest comedians. That, of course, is patent nonsense.

The list-makers were interested, not in vocational excellence, but political purity. It was a period during which an anti-Communist right wing, led by an ambitious Wisconsin senator named Joseph McCarthy and the federal House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), set the standards.

A fearful citizenry set about making lists to isolate themselves from anyone who might already be a carrier of the deadly contagion.

The movie studios and the television networks, under pressure from their patriotic fans and sponsors, bent over backwards to co-operate with the Red-baiters. They were among the most vigourous (and visible) of the list-makers.

Ritt's film, more than 20 years after the fact, looks at one result of TV's blacklist, the use of fronts. Howard Prince (Woody Allen) is a cashier in a bar until an old friend, left-leaning television writer Alfred Miller (Michael Murphy), loses his job.

For 10 percent of the selling price, Prince agrees to put his name on Miller's scripts, thus becoming the blacklisted writer's "front."

Prince's major market is Grand Central, a dramatic anthology series produced by Phil Sussman (Herschel Bernardi) and hosted by Hecky Brown (Zero Mostel). In the process of establishing himself, Prince falls for script editor Florence Barrett (Andrea Marcovicci), a Connecticut girl who admits that "in my family the biggest sin was to raise your voice."

Prince's reply to this: "In my family the biggest sin was to buy retail."

Okay. The obvious question is, who turned Woody Allen loose on this project? If Ritt is serious about his subject, then Allen's self-indulgent schlepp humour — his is not a dramatic performance — is completely out of place.

Everybody else plays it straight. Actor Murphy’s writer character suffers from ulcers and angst attacks. Mostel’s Hecky Brown — obviously supposed to be one of "our funniest comedians" — sweats, sighs and goes into a suicidal depression. As their producer, Bernardi is constantly conscience-stricken.

If Ritt was serious, why didn't he hire an actor — a Dustin Hoffman or a Richard Dreyfuss, say — instead of a stand-up comic? Perhaps he was trying for a kind of absurdist humour.

If so, he misses. Allen is not so much absurd as inane.

Whatever the intent, the project got out of control and went disastrously wrong. Despite the vintage cars on the street, Robert Drumheller's set decoration doesn't even look 1950s.

Like Allen's performance, the film's style is numbingly unimpressive.

Here’s the irony. The Front is a film that claims that the finest, the best, and the funniest were blacklisted. In the 1950s, they might have been guilty of unfashionable political idealism. Today [1976], the charge is false advertising.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1976. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: History repeats itself, Karl Marx observed in his 1852 essay The 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon, “first as tragedy, then as farce.” How appropriate that a quote from the author of The Communist Manifesto (1848) should be the best description of the life and legacy of America’s post-war witchfinder general “Tailgunner Joe” McCarthy. Like the current U.S. president, the senator from Wisconsin was a notorious vulgarian who rose to prominence on a platform of fear and ultra-nationalism (ideas that were already abroad in the land). Like D. John Trump, J. Raymond McCarthy exploited the the nation’s fear that it was under siege from enemies within. He is remembered for his crusade to drain the swamp of Communist infiltrators in the State Department, and the promotion of blacklists in every walk of life.

As a senator, McCarthy was not a member of HUAC (a standing committee of the House of Representatives from 1945 to 1975). He was its most powerful ally, though, working in parallel with it in the pursuit of subversives, the vilification of celebrities and the ruination of lives. By 1953, cartoonists and comedians were mocking him and, on March 9, 1954, America’s most respected television journalist, Edward R. Murrow, called McCarthy to account in the single most famous edition of his current affairs series, See It Now. It was the beginning of the end for the unrepentant demagogue.

In 2005, actor-activist George Clooney released Good Night, and Good Luck, a drama based on that moment in broadcast history. The son of a newsman, Clooney wrote, directed and performed in the feature film, an Oscar nominee in nine categories including best picture, actor — David Strathairn as Murrow — and director.

The Front, coming nearly a generation after McCarthy’s death, was an attempt to recall the shame of the blacklists in the year of the U.S. bicentennial. In 1976, filmgoers preferred the story of a never-say-die loser (Rocky) or newsmen pursuing political malfeasance (All the President’s Men), pictures that put a positive spin on their American dream. Martin Ritt’s movie remains something of an oddment, an attempt to wrap the farce and the tragedy in the same cinematic package.