Friday, July 20, 1973

ETAT DE SIEGE (State of Siege). Written by Franco Solinas, based on a story by Solinas and Constantin Costa-Gavras. Music by Mikis Theodorakis. Directed by Constantin Costa-Gavras. Running time: 120 miinutes. Mature entertainment. In French with English subtitles.

GOOD FILMS, AND YOU can count Etat de Siege as one of the best in this year's Varsity Festival package, sometimes raise as many questions as bad ones. In this case, the question that piques me most is quite beyond the content of the film itself

Why is it, I find myself wondering, that with so many self-proclaimed "people's film makers" running around, there are so few real "people's films"? The sad fact is that as long as there has been cinema, there have been activists, and there have been social critics willing to sit around mumbling about creating "revolutionary" cinema.

Some, like former French critic Jean-Luc Godard, have actually gone out and made some movies. The irony is that, while Godard announces his dedication to social change, his films fail to resonate with the broad masses he claims to serve.

Though he has managed to attract a chorus of acolytes to sing his praises, he has never really reached "the people." As a cinematic revolutionary, he is a failure. Like so many other movie "geniuses," he violates a cardinal rule of mass arts: his films lack mass appeal.

That's why Constantin Costa-Gavras is such a rare find. Here is a director passionately committed to the cause of social justice who makes brilliant, exciting and entertaining movies. Here is a polemicist with wit, charm, style and skill.

His latest film, the French-language Etat de Siege (State of Siege), brims over with mass appeal. A fast-moving thriller, it also has a solid underpinning of political commentary and investigative reporting.

The setting this time is an unnamed Latin American democracy. Like his unnamed monarchy in 1969's Z (a country that was clearly modern Greece), and his unnamed communist state in 1970's The Confession (clearly Czechoslovakia), the country in State of Siege is clearly Uruguay.

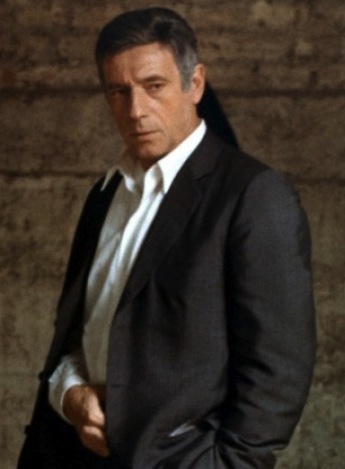

Working with Costa-Gavras yet again is Yves Montand. The wearily handsome French actor starred in both previous projects, first as the murdered liberal parliamentarian in Z, and then as The Confession's communist scapegoat. Here he is a representative of the U.S. Agency for International Development (A.I.D.) named Philip Michael Santore.

The film opens with a combined police and military dragnet locating his body. Santore, it turns out, has been killed by members of the Tupamaro urban guerilla movement. Cutting quickly to Santore's state funeral, Costa-Gavras reveals that some important people have boycotted the ceremony, including the chancellor of the university and the archbishop of Montevideo.

With swiftness and economy, the director has involved us with two questions: why would allegedly nationalist guerillas kill a man apparently rendering a service to their country? Why would important community leaders refuse to do him honour in death?

Flashing back to the day of Santore's kidnapping, Costa-Gavras introduces his Tupamoros. In a tightly-paced sequence, we meet a corps of intense, but attractive guerillas, made up of slim, purposeful men and intelligent focused women.

Mikis Theodorakis, who provided the memorable score for Z, here offers a jaunty, reed-dominated theme for the Tupamaros, a bit of background music that identifies them as heroic rather than sinister. As they commandeer cars in the city streets, the exploit has the air of a college prank. The drivers whose vehicles they take display an equanimity that comes close to affection.

They are not pranksters, though. In their early morning sweep, they manage to net the Brazilian consul and Santore, the American advisor. They announce that both men are being interrogated by a "people's tribunal," and that their release will be predicated on the release by the government of "political prisoners."

Almost immediately, the press begins digging. The question: just who is this Santore fellow? (Here Costa-Gavras shows himself to be a gifted psychologist. As long as his films continue to portray newsmen as fearless truth-seekers, he will never have to worry about negative reviews.)

Needless to say, Santore's mission emerges as something quite sinister, the reasons for his incarceration more justified than the A.I.D. organization's altruistic title would lead us to believe. As he faces his hooded interrogator, a knowledgeable prober named Lopez (Renato Salvatori), and as the newspapermen — including a hard-bitten old political commentator named Ducas (O.E. Hesse) — dig for their story, there emerges a tale of political intrigue, involvement in right-wing coups, of torture, terror and methodical murder.

Tension mounts and the scales of audience sympathy, originally weighted so heavily in favour of the family man in the flag-draped coffin, begin to shift. As they shift, Costa-Gavras strips away the veneer of selfless generosity from America's somewhat self-serving image.

There's no denying the power of Costa-Gavras's argument. No less an authority than iconic director George Stevens, currently [1973] director of the American Film Institute, has declared State of Siege too hot to handle.

Originally booked to play the AFI's premiere festival in Washington's John F. Kennedy Center for the Arts, the Franco-Italian co-production was pulled from the program by Stevens himself. Deeming it inappropriate for the place or the occasion because of its subject matter (political assassination), Stevens found himself at the centre of a controversy that turned his event into a shambles of protest, withdrawals and last minute substitutions.

Vancouverites have no need to worry. State of Siege is tonight's [July 20, 1973] 7:30 Varsity Festival feature. It deserves the quickest possible return booking.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1973. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: The career of Costa-Gavras offers some interesting insights into how the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences enforces American values and tacks with the prevailing political winds. The Greek-born director's French-language feature Z (1969) identified him as a powerful a new talent, and he was welcomed into the club with five Oscar nominations, including best director. Z's story, a tale of political corruption set in Greece circa 1963, had enough cred among Hollywood's liberals to win the best foreign language picture prize. State of Siege, by contrast, directly implicated the U.S. in serious wrongdoing in Uruguay in 1970. In doing so, Costa-Gavras crossed an invisible line, and the Academy's response was to shun him. Apparently unchastened, he continued making movies. His first English-language film, 1982's Missing, starred Jack Lemmon as a relentless American father searching for the truth about his son, "disappeared" during the 1973 Chilean coup. Walking the line between inspiration and provocation, the Costa-Gavras feature earned five nominations, including best actor (Lemmon), best actress (Sissy Spacek) and best picture. The director himself won the best adapted screenplay Oscar. As if to demonstrate that he had not in fact joined the "liberal" Academy club, his next picture, 1983's Hanna K., starred Jill Clayburgh as an Israeli-American lawyer who defends a Palestinian accused of terrorism. That movie kicked the third rail of Hollywood film-making, setting off a storm of criticism that severely limited its U.S. release. All was forgiven in 1989, though, with the release of Music Box, the story of a Chicago attorney, played by Jessica Lange, who is called upon to defend her own father, a Hungarian immigrant accused of war crimes. Lange took home the year's best actress Oscar, and her director returned to Europe once again, to continue making movies in his own way.