Wednesday, December 9, 1981.

SEATTLE — When Peter Bogdanovich arrived in Hollywood, movies were his life. New York-born, he had spent his first 25 years looking at them, programming them, thinking, talking and writing about them.

Today [1981], 17 years later, his life is a movie. At 42, Bogdanovich is on the road promoting They All Laughed, his tenth feature and a picture he unhesitatingly calls “autobiographical.”

The film, a romantic comedy set in contemporary New York City, stars Ben Gazzara and John Ritter as private detectives assigned to watch women suspected of marital infidelities. Gazzara is shadowing Audrey Hepburn.

“Ben is playing me at 45,” Bogdanovich says. The character he plays, John Russo, “doesn't have any idea where he's going. He just feels that he's missed something.”

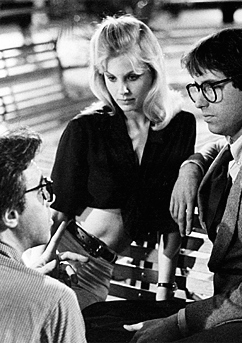

But, in the film, it is John Ritter, wearing the director's own coat and glasses, who looks just like Peter Bogdanovich. “John is me at 30. The part was written for me, really.”

But “I decided that I was too old to play it.”

As the love-struck Charles Rutledge, Ritter woos and wins wayward wife Dolores Martin, played by former Playboy magazine model Dorothy Stratten. It was here that life and art intersected with tragic results.

In terms of the Bogdanovich “autobiography,” Stratten’s character represents Cybill Shepherd, the photographer's model who turned the director's head during the making of 1971’s The Last Picture Show. They subsequently lived together and Bogdanovich made every effort to make Shepherd a star.

During the making of They All Laughed, history repeated itself. While Dolores and Charles were falling in love on camera, Peter and Dorothy were doing the same thing in real life.

Like her film character, Stratten had a jealous husband. Although the story of Dolores and Charles has a happy ending, the real world tale of Peter and Dorothy did not.

In the early afternoon of August 14, 1980, Stratten and her estranged husband Paul Snider died of gunshot wounds in their California home. Los Angeles police and coroners concluded that Snider murdered Stratten, then turned the gun on himself.

Bogdanovich completed work on the film, determined that it would be his personal tribute to the young Vancouver-born actress. Her co-stars agreed that the picture should open with a dedication “To Dorothy.”

When the film was delivered to 20th Century-Fox, the distributor proved less dedicated to it than the filmmaker. Relations between Fox and the picture’s producer, Time-Life Films, were already strained over another matter and, following some test screenings, Fox decided to shelve the dream-like comedy.

Bogdanovich wasn't about to let that happen. “I wasn't going to let (Dorothy's) only film go down the drain because of a bunch of people arguing about money.”

The director bought back the distribution rights, and is distributing They All Laughed through his own company, Moon Pictures, a new production and distribution entity.

“I don’t want (the distribution companies) telling me what to do,” he says vehemently. “They don't know how to make pictures, and they don't know how to sell them. It's the difficult picture that makes a distributor, not an easy one.”

In a sense, the director has now come full circle. In 1964, Esquire magazine film columnist Peter Bogdanovich drove to California “with the express purpose of continuing to write and, hopefully, to make a movie,” he said.

His first film work was for exploitation filmmaker Roger Corman. His first feature, 1968’s Targets, was made for Corman. Thereafter, his career resembled a holiday rocket.

Targets, a gripping, tightly-crafted thriller, was the impressive launch. The Last Picture Show (1971), with nominations for eight Oscars, including best picture and direction, was the first great explosion.

The comedies What's Up, Doc? (1972) and Paper Moon (1973) extended the dazzling display. Then, with a loud crackle, the fire seemed to fade.

His next two films, a languid period piece called Daisy Miller (1974) and the musical comedy At Long Last Love (1975), were expensive, ambitious attempts to establish his discovery, Cybill Shepherd, as a major film star.

The public did not find Shepherd as charming as her director did, and both pictures bombed at the box office. Then came Nickelodeon (1976), a costly comedy about early Hollywood. When it failed, Bogdanovich’s career seemed to be in ashes.

At this point, Corman, his old mentor, re-entered the picture to underwrite Saint Jack, a small personal project that Bogdanovich had developed. Based on Paul Theroux's novel about expatriates in 1960s Singapore, it was shot on the cheap in the Philippines.

In it, Bogdanovich says, the story deliberately mirrored the events of his life. Its three movements showed its hero, pimp and brothel entrepreneur Jack Flowers (Ben Gazzara), realizing his life's ambition, adjusting his ambitions to an an unsavoury reality, then adjusting again when his world collapses in upon him.

Saint Jack described “exactly how I felt about Hollywood,” he told me. He had planned to conclude the film with a "four-page scene” in which Jack and an untrustworthy CIA agent (played by Bogdanovich himself) “talk about the meaning of it all.”

After rehearsing it with actor Gaziara, he realized that it “just didn't play.” They discussed it, and Gazzara suggested condensing the wordy exchange to its essence.

“Ben said ‘why don’t I just say fuck it? It’s your fuck-Hollywood movie, and you'll never work after this anyway'.” Gazzara was only partially right.

Bogdanovich may never work for anyone else’s company again. The critical response to Saint Jack was generally positive and the deal to make They All Laughed followed.

His Moon Pictures, characterized by the trade paper Variety as “a Corman-type shop,” currently has the rights to 21 properties, with its boss planning to direct perhaps two in 1982.

With a number of published works of film history to his credit, Bogdanovich used to be criticized for producing pictures recalling the styles of another generation's film masters.

Today, his ideas come not from archives, but from within himself.

“Hemingway said ‘write about what you know,” he says with conviction. “I don't know what the hell else to write about.”

The above is a restored version of a Province interview by Michael Walsh originally published in 1981. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: The independently-distributed They All Laughed had its Canadian premiere at Vancouver’s independently-owned Ridge Theatre. I had followed Peter Bogdanovich’s directorial career with considerable interest, and I gladly accepted the invitation to interview him. Our meeting was complicated by the fact that I had to travel to Seattle to take it. And that, as they say, is another story.

It is a story that, to the best of my knowledge, didn't see print until years later. It’s based on my recollections of two conversations that occurred 35 years ago, and contains at least one purported fact that I can't corroborate with a simple Internet search. The first conversation was with an editor from our news desk, who spoke to me the day before I drove down to Seattle. He told me that there was a rumour going around that Peter Bogdanovich couldn’t cross the border into Canada because there was a warrant out for his arrest. According to the news editor, the charges involved sex with a minor, specifically the late Dorothy Stratten’s 13-year-old sister Louise. Ask him about it, the editor said.

I refused, politely reminding him that I did not work in his department, and that I didn’t do gossip. (OK, maybe I wasn’t polite. I never really liked that guy.) Even so, he’d put the thought in my head, and I was a reporter, after all. The next day, I had an open and congenial conversation with Bogdanovich which became the above interview. When we were done, I closed my notebook and put my pen in my jacket pocket, signalling that I really didn’t expect him to answer my next question. Then, in the least confrontational way that I could, I told him what I’d been told the day before. There was an awkward silence, then he calmly offered his non-answer answer. Ignoring the question of warrants, he said that he was working on book about Dorothy, her life and her death. And we were done. Published in 1984, The Killing of the Unicorn: Dorothy Stratten 1960-1980 includes an acknowledgement to Stratten’s mother, brother and sister for the “encouragement, loyalty and love (that) made it possible to survive the catastrophe that changed all of our lives.”

In April 1985, the 16-year-old Louise sued her step-father Burl Eldridge and magazine publisher Hugh Hefner for slander, saying they had told reporters that Bogdanovich had seduced her when she was 13 and had had sex with her mother after Dorothy’s murder. She later dropped the lawsuit. In late 1988, the 20-year-old Louise married Peter Bogdanovich, then 49, in a private ceremony in suburban Vancouver. They divorced in 2001, but not before collaborating on the screenplay for the director’s She’s Funny That Way, an independent feature comedy released in 2015. Peter Bogdanovich turns 77 today (July 30).

See also: To date, the Reeling Back review archive contains only one Peter Bogdanovich feature, 1973’s Paper Moon, the period comedy for which Tatum O’Neal won her Academy Award.