Monday, June 27, 1977.

ROLLERCOASTER. Written by Richard Levinson and William Link. Music by Lalo Schifrin. Directed by James Goldstone. Running time: 119 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: Parents — may frighten some children.

SOMEBODY AT UNIVERSAL PICTURES remembers 3-D. The biggest entertainment gimmick of the 1950s, three-dimensional movies were supposed to make people forget television and return to the picture palaces.

It worked briefly. After a while, though, filmgoers got tired of lions in their laps and one-size-fits-all glasses sliding down their noses.

In the rush to exploit the new depth-vision technology, film-makers made a disproportionate number of bad pictures. People stopped coming.

Universal is not about to see that happen to Sensurround. Although the studio's patented, theatre-rattling sound system is less of a novelty than 3-D, it's being treated rather more carefully.

Three years ago [1974], it was enough to destroy Los Angeles. Earthquake rocked audiences with earth tremors, bursting dams and the sight of hero Charlton Heston actually getting killed.

Last summer [1976], Sensurround went to war. Midway refought a Second World War sea battle and offered cannon duels, air attacks, bursting bombs and the sight of hero Charlton Heston getting killed yet again.

Heston seems to have missed the casting call for Rollercoaster. Indeed, the all-star-cast formula has been abandoned for this, the third and arguably the best of the Sensurround epics.

Here, director James Goldstone manages something the 3-D entrepreneurs seldom could — he's made a good movie. There are thrills aplenty in his picture, a film that would be top entertainment even without Sensurround.

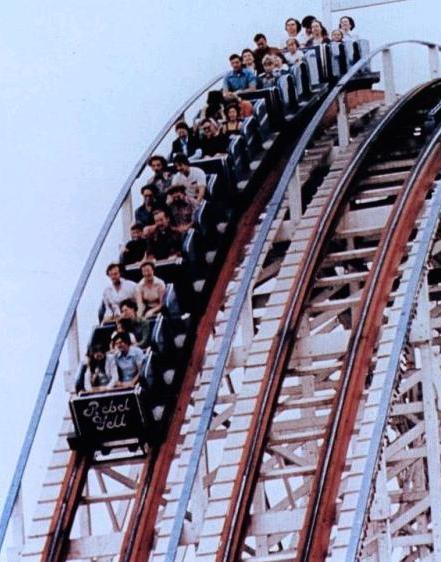

It opens with a purposeful-looking Timothy Bottoms paying particular attention to the early morning maintenance on The Rocket, the Ocean View Amusement Park's roller-coaster. When the staff inspection is done, Bottoms dons coveralls and a hardhat, climbs up the track and places a small, radio-controlled bomb on one of the coaster's highest turns.

Bottoms plays the nameless villain of the piece. A cool, ruthless extortionist, he is not at all squeamish about killing a dozen or so people to demonstrate to amusement park owners just how vulnerable their operations really are.

In return for a million dollars, he'll promise not to kill any more.

Goldstone, who failed to generate any excitement with his last film, the lacklustre Swashbuckler [1976], redeems himself here. At the heart of his success is a first-rate script. A tight, funny screenplay, it is the contribution of a pair of former TV writers, Richard Levinson and William Link, the team that created broadcast hits such as Mannix and Columbo.

In Bottoms’s blackmailer, they have created a perversely fascinating character. Intelligent and capable, he seems to have considered every possible contingency.

By contrast, Harry Calder (George Segal), the standards-and-safety inspector dispatched to the scene, looks as if he's about to come apart. Recently divorced, his career is at a standstill, and he is in shock therapy to break his cigarette habit.

Everybody abuses Harry. His boss, the dapper Simon Davenport (Henry Fonda), tries but fails.

FBI special agent Hoyt (Richard Widmark), with more suasion at his disposal, is pushing him around with somewhat greater success.

What Harry really resents, though, is the way in which the mysterious bomber insists on involving him in his plot. Like Robert Redford in last year’s [1975] Three Days of the Condor, Harry feels menaced from all sides.

Starting with a solid set of characters involved in believable relationships, Goldstone plays the Hitchcockian trick of spiking tension with humour. Throughout, his cast gives him exactly what's wanted.

Bottoms, his jaw set at an intense angle, slides effortlessly into the kind of outwardly rational psycho role that used to be an Anthony Perkins specialty.

Segal, with the most fully-developed part, gives his best performance in years. He is the 1970s version of the common man caught up in an uncommon situation.

A pair of old pros, Fonda and Widmark play well in what amount to supporting roles. The surprise is that Sensurround, after two star performances, is also playing a supporting role.

As effective as it is, rumbling to life every time the camera goes for a roller-coaster ride, the big speakers provide enhancement, rather than the reason, for the movie. Without them, Rollercoaster would still be a thrill.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1977. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Rollercoaster director James Goldstone took his film crew to at least three major U.S. amusement parks for location filming. Although it was not included on his itinerary, Vancouver’s own historic roller-coaster has managed its share of screen roles. Playland’s star attraction has appeared in many locally-filmed television shows, and had starring roles in such theatrical features as 1994’s Hideaway, playing opposite Jeff Goldblum and Christine Lahti, and Mark Wahlberg and Reese Witherspoon enjoy the ride in Fear (1996). It’s a more sinister player in 2004’s Riding the Bullet, an adaptation of a Stephen King novella, and in the supernatural shocker Final Destination 3 (2006).

A television director from the mid-1950s, James Goldstone made his lasting impact on the small screen. When he died in 1999, obituary writers, such as the Independent’s Anthony Hayward, said that “he is best remembered for the pilot episode of Star Trek.” Called Where No Man Has Gone Before, it was actually the show’s second pilot but, because it was the one that sold the idea to NBC network executives, it is legendary among Trek fans. Goldstone made his feature film debut in 1968 with a western, A Man Called Gannon. For the next decade he made genre pictures, including the indifferent Swashbuckler, a 1976 pirate film that suffered from the fact that its producers could only afford one period sailing ship.

The moderate box office success of Rollercoaster, made on a $9-million budget, resulted in Goldstone being tapped by producer Irwin Allen to helm his $20-million When Time Ran Out . . . An all-star epic, the 1980 release had the likes of Paul Newman, Jacqueline Bisset, William Holden and Ernest Borgnine reacting to an erupting volcano. Sadly, the title was prophetic. Time had indeed run out on the disaster movie cycle, the movie was a major financial disaster, and Goldstone’s 10th big screen feature was his last. He returned to television, where he specialized in such historical dramas as the Emmy-award winning Kent State (1981), Charles and Diana: A Royal Love Story (1982), Rita Hayworth: The Love Goddess (1983) and Calamity Jane (1984).

See also: As it turned out, Rollercoaster was third of only four films released in the theatre-shaking Sensurround sound system. For more on that subject, see the Afterword to my review of Earthquake.