Friday, January 17, 1975

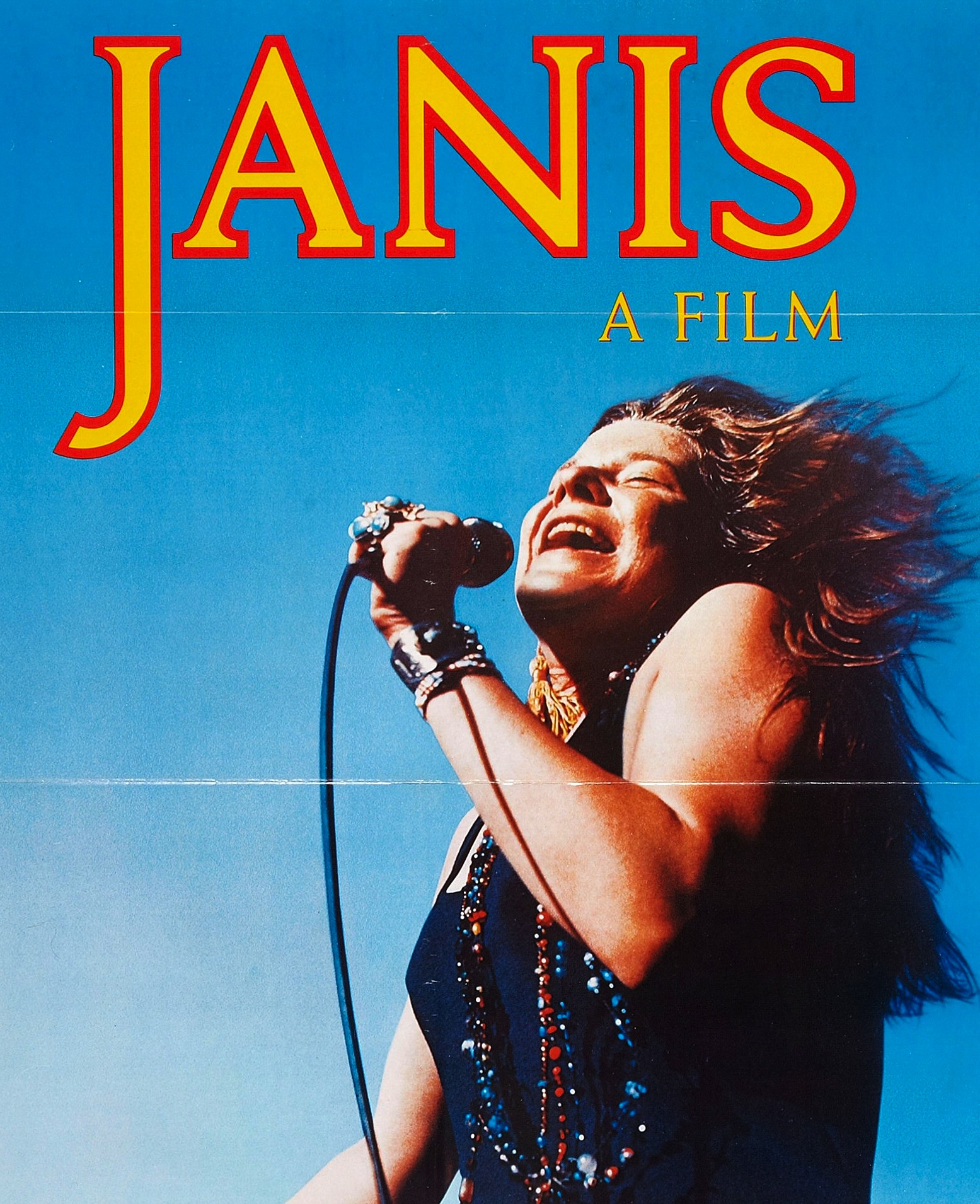

JANIS. A musical documentary featuring Janls Joplin. Music edited by Bruce Nyznik. Co-written by Seaton Findlay. Co-written, edited and directed by Howard Alk. Running time: 96 minutes. General entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: occasional coarse language.

JANIS JOPLIN WAS UNIQUE. A plump, introverted white girl, she came out of Texas by way of San Francisco to sing the blues, live the blues and, eventually, to die the blues.

In a television interview with Dick Cavett, she recalled her Texas neighbours with bitterness. "They laughed me out of school, out of town and out of the state."

In another interview, recorded In London, she described what her small-town parents expected of her, expectations she could never meet. "They haven't forgiven me yet," she said ruefully.

Her death on the morning of Sunday, October 4, 1970, at the age of 27, is officially attributed to "an accidental overdose of heroin."

Ottawa documentarist Frank "Budge" Crawley saw Joplin perform in Toronto shortly before her death. He wanted to see her dynamic story put on film. Ironically, after her death, it was Joplin's unforgiving parents who had to give their approval to the final product.

"If you can make a film of what Janis meant to her fans, you can go ahead," Crawley recalls her mother Dorothy Joplin saying. "However, you are still doing it at your risk. We must like the film."

The resulting feature, called simply Janis, walks its fine line with considerable skill. An estimated 70 pounds of contracts, agreements and releases were necessary to secure the various interviews, performances, still photos and recordings used in the final cut.

Throughout, there is no mention of the tragic circumstances of the singer's death. Indeed, the film doesn't make clear that she is dead. One of her trademarks, the ever-present bottle of Southern Comfort, is never present on the screen.

Crawley's movie, written, edited and directed by Howard Alk and Seaton Findlay, consists of Joplin interviews and performances. Janis is seen singing 13 numbers, performances filmed in San Francisco, Toronto and Frankfurt, as well as at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival and Woodstock.

She is heard vocalizing two more: the film's opener, "Mercedes Benz," and its finale, "Me and Bobby McGee." In both cases, the impact of those recordings is enhanced by some clever photomontage work that includes a snapshot biography of the late singer.

Seen in a series of interviews, Joplin comes across as a sensitive, intelligent, vulnerable woman. Sharper than any of her questioners, her answers are often more honest and revealing than such situations require.

While a guest on the Dick Cavett television show, an interview in which she matches the professional host parry for thrust, she reveals that she is going back to her 10th anniversary high school reunion. In a Hollywood drama, the occasion would have been a triumph.

For Janis, a real person living in an almost unbearably real world, the whole idea was a mistake. A local TV crew was on hand to record the event and the reactions of her former classmates.

As a group, they seem to regard her presence as an intrusion. A collection of accountants, hardware clerks, used car dealers and housewives, they do not take joy in their successful sister's return. The resentment in the room is as thick as a Texas steak.

Janis sees and feels it. Visibly upset, she is pummelled to the verge of tears by a series of stupid questions from a TV reporter. No, she finally admits, nobody ever asked her to the senior prom. Less than a month later, she was dead.

Janis, the film, can't tell the whole story. The inferences are there, though. The lady sang the blues. She was her music, and her music is here.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1974. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Mythologized as the "the Judy Garland of Rock," Janis Joplin's drug-related death put her among the era's tragic trio that included Jimi Hendrix (died 1979) and Jim Morrison (died 1971). Following the release of the1974 documentary, there was considerable interest in Hollywood in making a big-budget biopic. Prospective producers faced the same problem as Crawley. The Joplin family retained the right to refuse its approval. One attempt, director Mark Rydell's 1979 feature The Rose, was heavily fictionalized to get around the rights problem. Bette Midler's performance as the tragic, Joplin-like Mary Rose Foster earned the singer her first best actress Oscar nomination. According to Guardian newspaper correspondent Priya Elan, a number of recent attempts to film her story have languished in "Development Hell." In his August 2010 article, Elan includes titles such as Piece of My Heart (with Renee Zellweger), The Gospel According to Janis (with Zooey Deschanel) and Janis Joplin: Get It While You Can (with Amy Adams), none of which were actually made.

Howard Alk, a Chicagoan who relocated to Ottawa in the early 1970s, arrived in Canada with a background in political documentary — he directed 1971's incendiary Black Panther feature The Murder of Fred Hampton — an interest in rock music and a sensitivity to the drug scene. It was this combination of talents that made him Crawley's choice to direct Janis. An African-American, Alk was a close friend of one of the era's great survivors, singer Bob Dylan. In 1978, he photographed and edited Dylan's directorial debut feature, the 292-minute Renaldo and Clara. Like Janis Joplin, Howard Alk was a heroin addict. Like her, his 1982 death was officially attributed to "an accidental overdose."