Monday, February 3, 1975

IN THE WARM, DIFFUSE light of late afternoon, the office towers strung out along West Georgia take on a subtle golden glow. Through the picture window at the end of the hotel corridor where he stands waiting for an elevator, "Budge" Crawley can see clear across to the North Shore."There's good light out here. Marvellous light. And the nice thing is that today we've got film that's fast enough to catch those soft tones."

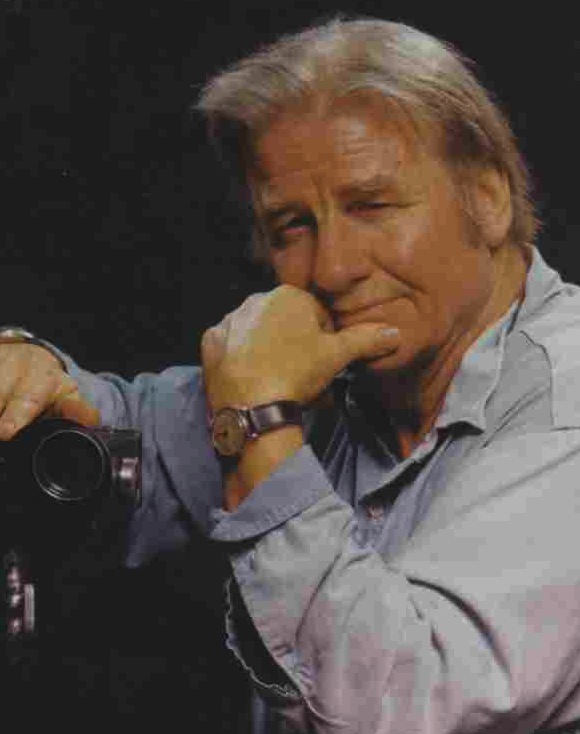

Frank Radford Crawley has been sensitive to the light for a lot of years. Born in 1911, the Queen's University-trained accountant decided to get into filmmaking in the late 1930s.

The man everyone knows as "Budge" won his first major international award in 1938. It was for a film he shot while on his honeymoon.

One of the grand old men of the Canadian film industry, Crawley is in town today [1975] promoting his latest enterprise, Janis, a feature-length musical biography of blues singer Janis Joplin. The film was premiered last fall at the San Francisco Film festival, where it collected effusive reviews and proved itself at the box office in a test release.

It seems that a Canadian has something to teach Americans about feature filmmaking. Even more surprising, it seems that Crawley, 64, is showing them how to handle one of their newest film forms, the rock-documentary, a kind of youth-oriented musical journalism that is only a few years old.

"There's a tradition of good documentary filmmaking up here," Crawley says. "I'm not saying that Americans can't do it, but here we go right back to the early days of the Film Board. We did a lot of films for John Grierson when he was film commissioner," Crawley recalls.

Grierson, the Scot who founded Canada's National Film Board in 1939, was the man who "invented the term 'documentary,'" Crawley tells me. He also gave Crawley's own Ottawa-based company a boost by subcontracting a number of early NFB projects to the young moviemaker.

From 1938 onward, Crawley Films Ltd. was in the business of making what are known as sponsored films. As a company, it took on contracts and produced documentary shorts for both educational and industrial use. One such film was The Loon's Necklace, a movie based on West Coast Indian art and legend.

Made for the Imperial Oil Company, it remains memorable. It's also historically important as the first "best picture" winner at the inaugural Canadian Film Awards ceremonies in 1948.

"The whole Canadian film industry, with a few exceptions, has been based on documentary filmmaking," Crawley says. He doesn't mention that one of the most ambitious early exceptions was Crawley's own RCMP, a series of half-hour dramas produced for CBC-TV [1959-1960], and sold internationally.

"Those of us who wanted to become filmmakers in Canada, perforce made documentaries because it was not feasible to finance or put together features," he says. Nevertheless, in 1964, several years before there was either a Canadian Film Development Corporation [renamed Telefilm Canada in 1984] or a growing national film scene, independent Crawley Films took a flyer at a feature.

The picture's name was The Luck of Ginger Coffey. Based on Brian Moore's 1960 novel about an irresponsible Irish immigrant in Montreal, it starred Robert Shaw and Mary Ure. It was good, but "I haven't got my money back yet," Crawley says.

"We were naive — not that we still aren't — in the distribution deal we made with (New York's) Walter Reade Organization," Crawley recalls. "It didn't get cinema distribution that amounted to anything."

On the other hand, he says, "it's had fabulous television distribution, although I don't think we get an honest count . . . every time I write a letter to New York and say 'we haven't had a return for a while,' I get a piece of paper with a cheque attached."

Keeping track of television rentals Is a difficult thing, Crawley says. Recently a friend came back from a trip where "he picked up the American ratings on television (performance). He said there were virtually no A-ratings.

"Ginger Coffey was rated B-2, which is a very high rating. If they get a B-2 rating, it had to have a lot of distribution, and they haven't paid us for a lot of distribution.

"What you've got to do is go down to New York and say 'come on, now. We have audit rights.' At that point, probably, they'll give you a cheque," he said.

"I suppose Canadians are known as good documentary filmmakers partly because of the NFB, and also because of the economics involved. English-speaking Canadians have been shut out of the feature-film market."

Perhaps. But that hasn't prevented Crawley from trying and, in the case of Janis, succeeding with a feature. His next project, called Everest, is "about a guy who literally skied down Mount Everest between 8,000 and 9,000 feet, then fell 1,300 feet, and almost fell into a crevasse."

Originally a Japanese project — the skier was a Japanese adventurer named Yuichiro Miura — Crawley acquired the original footage in Los Angeles, added to it, and expects to have his film in release within three months.

By now, the light on Georgia Street has changed. So has Crawley's vantage point. Sitting in the rooftop lounge, he has seen the sun disappear beneath the horizon, and the North Shore mountains begin to blend into a night sky.

The lights on the far side of the inlet seem to be heaped in piles, like glowing nuggets. "Now," says Crawley, "that reminds me of a movie . . ."

The above is a restored version of a Province interview by Michael Walsh originally published in 1975. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: On the evening of March 29, 1976, "Budge" Crawley became the first Canadian to accept an Academy Award for making a feature film. His independently produced The Man Who Skied Down Everest won the Oscar as Best Documentary Feature. With the trophy in his hands, he faced the TV cameras and joked that "this is an American award for a Canadian film about a Japanese skier who skied down a Nepalese mountain." As for the "good light" that he remarked upon in our 1975 Vancouver conversation, it became better known to the international filmmaking community in the years that followed. By 1995, B.C. was one of the four largest motion-picture and television production centres in North America.

Thursday, May 27, 1976

SEATTLE , WA.

CANADIAN FILMMAKERS HAVE a problem. Government financial participation in their productions notwithstanding, their feature films are not getting into the foreign-owned distribution system, the real key to Canada's foreign-controlled theatre network.Academy Award-winning movie producer Budge Crawley has a solution. His proposal — federal carrot-stick legislation aimed at the distribution companies — cuts to the heart of the problem with remarkable directness.

"The answer," Crawley, 65, told me in an interview, "is a tax on film rentals. Tie that to a tax-credit system that gives the distributor a dollar's credit for every real dollar returned to the producer of a Canadian film that that distributor has in international distribution," he said.

"I think it's a pretty down-to-earth idea," said Crawley, who was in Seattle to participate in the annual [1976] Motion Picture Seminar of the Northwest. A Queen's University-trained accountant who won his first film-making award in 1938, he noted that the plan "has the added bonus of encouraging quality productions, not the stuff that shouldn't be made in the first place,"

Crawley's "idea" — he credits it to W.E. Harvey Hunt, former head of distribution for Crawley Films — has the advantage of covering all the bases and answering all the questions.

Exhibitors, the theatre-owning companies that would take the brunt of the financial punishment if the government were to act on the quota and levy recommendations put forward by the Council of Canadian Film-Makers (CCFM), have nothing to fear from the Crawley plan.

"George Destounis, who is against quota and levy, says it's the best idea he's heard." Crawley told Destounis of his plan in a conversation held shortly before the president of Famous Players, Ltd. left for the annual Cannes Film Festival.

"Everybody knows that (the American distribution companies) are taking in millions every year," he said. "What nobody really knows is how those earnings are funnelled out of the country. Believe me, it's no simple matter.

"On the other hand, it's relatively easy to check up on gross rentals. And that's the place to hit 'em." According to Crawley, it's time that the distributors, the middlemen of the movie business, opened their books to the taxman.

The Crawley plan should make the provinces happy.

For years, provincial politicians have heard their federal counterparts excusing Ottawa's lack of a firm film policy with the same tired cop-out: power over the theatres is a provincial matter. Crawley's plan does not directly involve theatres, nor any matter within provincial jurisdiction.

The federal government should also be happy.

The Crawley plan gives it an opportunity to fulfil its oft-stated policy promises unilaterally. "They don't have to go to the provinces to amend the tax act," Crawley said.

Canadian taxpayers have nothing to fear. Crawley, who has managed to make four feature films and win an Oscar without drawing one cent from the Canadian Film Development Corporation (CFDC), has little use for the federal film-funding agency,

"It's almost a theology in the revenue department that you don't tax for social purposes," Crawley said. "They don't like the idea of taking money away from American producers just to give it out to Canadian producers," he explained.

"Part of the idea is that the money doesn't go to (CFDC executive secretary) Mike Spencer. It goes into general revenues."

That way, Crawley said, the tax credit that a distributor earns for monies returned to Canadian filmmakers costs the Canadian taxpayer nothing. On the other hand, it would stimulate a good deal of interest among international distributors in the movies underwritten by the Canadian public through the CFDC, and certain other provisions of the tax act.

Filmgoers, however, won't have to worry about having Canadian films "forced down their throats." The Crawley plan "will make Canadians make decent pictures," he said. "It won't pay a distributor to take a bad picture, but it will create real competition among the majors for good Canadian films. And those films will get played all over the world."

Crawley, together with Harold Eady, president of the Association of Motion Picture Producers and Laboratories of Canada, and AMPPLA committeeman John Ross, visited federal finance minister Donald Macdonald in January. According to Crawley, Macdonald was most interested in their rentals tax/tax-credit plan.

Last week, just before Crawley left for Seattle, he was contacted by the secretary of state's office, and asked for further details. In Seattle, he moderated a panel discussion on Saturday [May 22, 1976] that brought together the government film co-ordinators of Idaho, Montana, Washington, Oregon, Alberta and B.C. to discuss the regional promotion of feature productions.

Crawley's Ottawa-based Crawley Films produced and directed The Man Who Skied Down Everest, winner of the 1975 Academy Award as Best Documentary Feature. He is currently involved in preproduction for a $1-million movie version of W.O. Mitchell's 1949 novel, Who Has Seen the Wind, to be shot this summer in Saskatchewan.

The above is a restored version of a Province interview by Michael Walsh originally published in 1976. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Who Has Seen the Wind was indeed shot on Saskatchewan locations in 1976. But, when director Allan King's feature arrived in theatres (in October 1977), "Budge" Crawley's name was nowhere to be seen in the credits. Though both the producer and director were deeply committed to the project, there were "creative differences," disputes detailed in Barbara Wade Rose's 1998 biography Budge: What Happened to Canada's King of Film (ECW Press; Toronto).

The official interest that then-federal finance minister Donald Macdonald had shown in Crawley's rentals tax / tax-credit plan was short lived. As film historian George Melnyk concludes in this 2004 study One Hundred Years of Canadian Cinema (University of Toronto Press; Toronto), "Budge Crawley believed in the private sector approach to film-making in Canada. He had staked his whole career on it and had won, but he won in the documentary mode alone. It was a pyrrhic victory. When he stepped into the non-sponsored realm of Canadian features, he became bogged down." Crawley's plan was brilliant, and dangerous to Canada's long-established systems of production and distribution. If adopted, it might have made the cinematic history recorded by Melnyk a very different story. Canada's "King of Film" died in 1987 at the age of 75.