Monday, August 27, 1973

A SOLID HANDSHAKE AND the firm, familiar voice belie the fact that Walter Pidgeon, a screen actor and onetime movie idol, will soon be 76 [in September, 1973]. In a career that spans nearly five decades, the 6'3" leading man has quite literally lived the history of Hollywood film.

Pidgeon has seen it all. Breaking into show business as a concert singer, he made the transition from stage to screen in the silent era, survived the transition from silents to sound, and successfully made the change from musical star to dramatic actor.

Seen in two new pictures in the last few months (The Neptune Factor and Harry in Your Pocket), Pidgeon refuses to even think about retirement.

"It's the people who make pictures who are the ones to retire you," he told me in an interview. "As long as someone wants me to work — if I like the story — I'll say okay."

Born and raised in New Brunswick, Pidgeon has always had a following in Canada, where his native-son status is seldom forgotten. Nevertheless, following service, and a serious injury, in the Dominion's First World War army, he left for the United States.

It was there, in Boston, that he married his childhood sweetheart. It was there, too, that a chance meeting with song and dance man Fred Astaire led to his first big break as a performer. Through the 1920s, he worked in vaudeville and established a name for himself as a pop singer.

In 1926, Hollywood called, and he left the stage for the screen. When the sound revolution came, Pidgeon, with his music hall resonance, was a natural for the "talkies." In sound recording, though, he discovered there was still a good deal of Canadian in him.

"The first picture that I heard in sound, and heard myself talk, I heard this 'aboot' and 'oot.' I remember there was one line in this picture I made for Warners called Sweet Kitty Bellairs [1930], and the line was 'It's just a mouse; the house is overrun with them.

"Well, the sound man came out of the booth and said, 'Good God, what did you say?' I told him the line and he said, 'Well, it didn't sound like that.'

"And I started right them, going 'abowt, howse, mowse, owt.' It took me years to get to the point where I didn't sound affected."

Though rid of his accent, Pidgeon maintained his Canadian citizenship. It wasn't until the Second World War that he gave any thought to taking the nationality of his adopted home.

"I'd been in the States from 1913 until 1940, and that's when I took out my papers. I had written up to Ottawa to see if they wanted me, and mentioned that I'd been in the artillery in the First World War.

"I got a very nice letter back from the war minister saying that if I had a son, he ought to be about the right age. They'd take him, but they weren't using horse-drawn artillery any more.

"I figured that America would be in it sooner or later. I thought that the best thing I could do, the honourable thing, was to take out my papers. Which I did. I've been a citizen now since '40."

At the time, Pidgeon was under contract to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the most major of the major film studios. Running it at the time was Louis B. Mayer. "He's from Canada, the same town I was born in — Saint John," Pidgeon said, adding that the movie magnate still had enough Canadian in him to loan one of his top leading men to the Ottawa government for a cross-country bond drive.

Pidgeon recalled that, before last summer [1972], the last time he'd been in Vancouver was 1942, on behalf of the war loan campaign.

Pidgeon was in demand to work for other studios as well as governments. Republic borrowed him the same year to star opposite John Wayne in Dark Command. ("I had an awful time getting MGM to let me do it . . . It was a heavy. They didn't want me to play heavies, but they liked the story.")

Universal had asked for him for its 1940 Deanna Durban musical It's A Date. United Artists featured him in the 1940 crime drama The House Across the Bay, and Twentieth Century-Fox borrowed him to star in the 1941 thriller Man Hunt. During the first eight years of his contract with Metro (1937-1945), he worked in more than 30 features.

Among them were two of the most memorable films of the time, How Green Was My Valley and Mrs. Miniver, the Oscar-winning best pictures of 1941 and 1942. The films also collected best director awards, with Oscars going to John Ford and William Wyler.

Recalling his work with the two men, Pidgeon was struck by "how completely different were the ways they went at the thing."

Ford "would do a lot of what we call 'cutting the shot.' He knew just how much he wanted of a certain thing, and that was it. He'd say 'cut,' and he had it.

"Ford would say, 'I want a shot here.' Where a lot of directors would play it, and play it, and play it, Ford would say he wanted 50 feet, say 'cut,' and go on for another one."

The economical, seemingly instinctive Ford style was in marked contrast with the more cerebral approach of Mrs. Miniver director Wyler, a filmmaker who reshot scenes over and over again.

"He's famous for that, for the number of takes he would take," Pidgeon said. "As I said to him one time, 'You know Willie, you're a perfectionist, but it's impossible to reach perfection. There's always the chance to get something better.'

"He wanted a lot of different shots that he could look over and pick from, you see. He might take 15 or 20 takes, then use the second or third one. That was his way of making pictures . . . He wasn't pressed for time so he took his time . . .

"I don't want to give the impression that Ford sloughed them off. If something wasn't right, he'd do it over. But he never did a lot of takes. Never did.

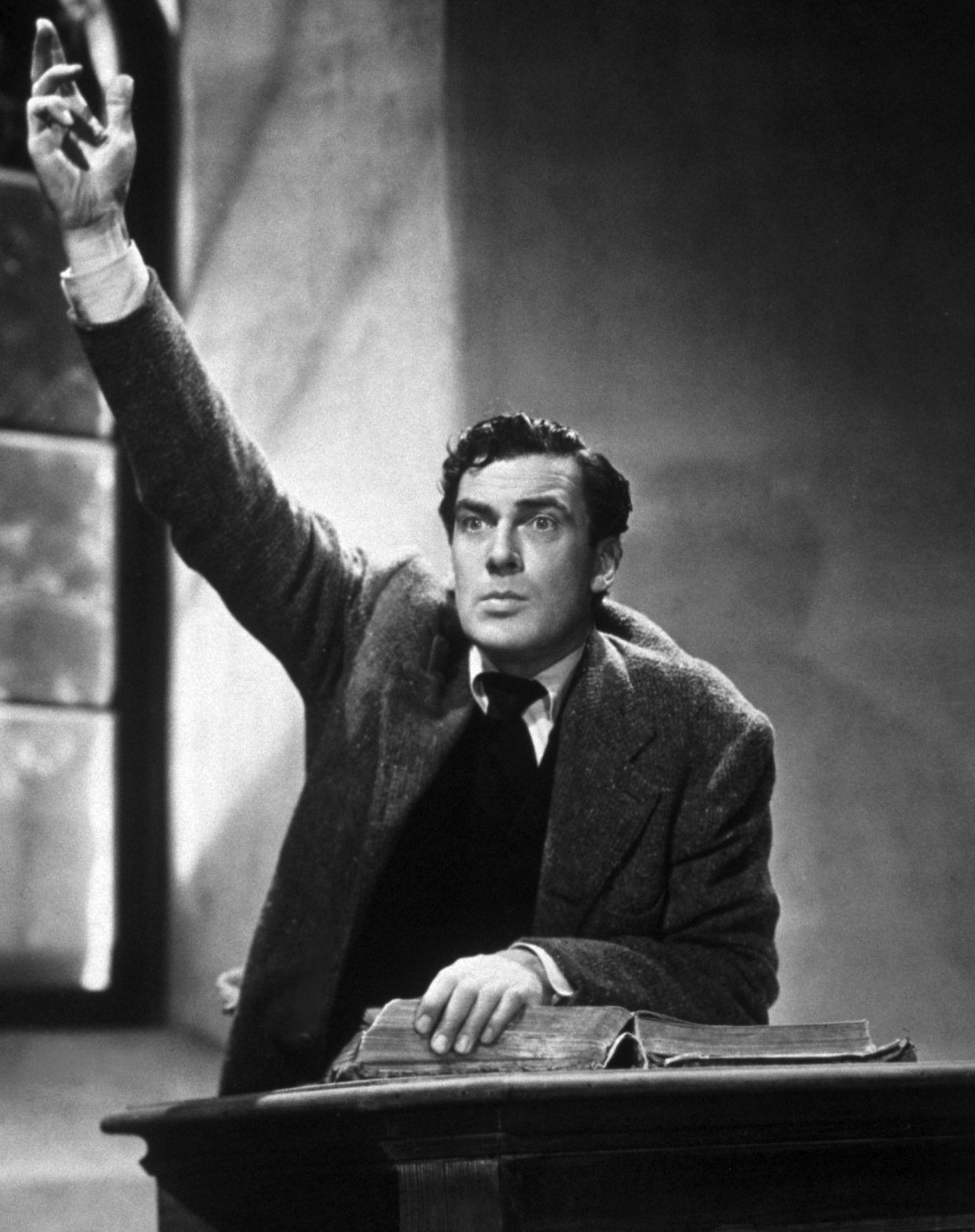

"I remember there was a scene in How Green Was My Valley where I stand up in the pulpit and bawl the congregation out. It's a long scene.

"It's when I start in and talk, and say "this is the last time I'll speak from this pulpit," and then go on to a long harangue. I talk for a few minutes in the pulpit, then I come down and talk to the deacons that are there, then call them hypocrites.

Pidgeon's eyes shone as he described the long-ago moment. "There's a wonderful line that I remember, where he says 'why do you come here? Why do you dress your hypocrisy in black, and parade it before your God on Sunday? From love? No! Fear has brought you here. Horrible, stupid, superstitious fear!'

"Then I walk on down to the back of the church, and then halfway up again, then through the aisle and out the door. It was a long scene.

"We rehearsed it after lunch. We walked it, and I had a mouthful of dialogue. And we came back. John said "do you know all the lines, Walter?'

"I said 'yeah,' and he said 'go through 'em, will ya?' And he said 'do it the way you feel it. Just whatever you feel on this thing.' And he had the cameraman there with him and watching it.

"When we got through, he said to the cameraman, 'can you shoot that?' The cameraman said 'yes, I can shoot it, but it'll take two hours to light it.'

"John said, 'go ahead and light it.' So he lit the thing, turned the camera on and started in. I got through it, and he said, 'cut. Let's have tea.'

"I said, 'John, er, ah, is it, er, aren't you going to do it again?'

"He said, 'Oh, good God. Didn't It feel right?'

"I said 'yeah, It felt great.'

He turned to Artie Mlller — that's the cameraman [an Oscar winner for his work on How Green Was My Valley] — 'He says it's perfect for him. So why do it over?'

"A lot of directors would have thought on a scene like that, 'I want to protect myself. I'll do another one, just in case.' But not Ford. He saw it and liked it.

A thorough professional, Pidgeon slipped in and out of more parts in those few years than many contemporary actors do in a career. For Ford, he played Merddyn Gruffydd, a Welsh clergyman in a period drama. For Wyler, he was Clem Miniver, a dutiful English husband during the Battle of Britain (a performance that earned Pidgeon his first best actor Oscar nomination).

Less heroically, he played the part of Civil War guerilla leader Will Cantrell (also known as Quantrill) for director Raoul Walsh (in Dark Command) and the obsessive Capt. Thorndyke, the English big game hunter who fails in his attempt to gun down Adolf Hitler in Fritz Lang's Man Hunt.

"An actor should be able to do most any role," Pidgeon insists. "I was never one of those guys that got terribly involved in a role. I learned the role, and then I never thought that this wasn't like the one I did the last time.

"I always remember something John McCormick, the great Irish tenor, said to me years ago. He was talking about singing, and he said, 'I don't sing.' He said, 'I'm the sound box. I sing in here. My heart sings.'

"I think there's something inside you, your emotion, that does the acting for you. You get one type of role in one picture, and that feeling you have inside does it for you. The next role may be an entirely different role, but you have feeling inside for that, too.

"You don't think how you're doing it, or think how you're playing it. It plays itself. Unless it's a badly written something — a screwy role that just isn't believable."

Older actors often get to play elder statesmen. In recent years, Pidgeon has been in the United States Senate twice. In Otto Preminger's Advise and Consent (1962), he played fictional Majority leader Robert Munson. More recently, in John Guillermin's Skyjacked (1972), he was Senator Arne Linder, a presidential confidant.

Though he publicly declared for Nixon in 1970, Pidgeon now prefers to avoid political discussions. He allows that the 1962 Preminger film, with its emphasis on Senate investigations and legislative-executive conflict was "ahead of its time," but he prefers not to talk about such highly-charged subjects as Watergate.

Lately, he's been working outside of the U.S. Where once all filming was done within Hollywood studio walls, location work is now standard, and Pidgeon's most recent roles were played in Canada.

Last year, he was in Halifax and Toronto, along with Yvette Mimieux, Ben Gazzara and Ernest Borgnine, to shoot director Daniel Petrie's The Neptune Factor. Despite the American stars, Pidgeon is quick to point out that the behind-the-camera crew was all Canadian.

"That was the one thing that worried me about the picture. When I read the script, I liked the script, but I realized there was going to be an awful lot of technical work in it, and I didn't know just how well they could do it up here.

"I want to tell you, the technical men they had in Toronto, who did all the work on that, down in Halifax and down in the Bahamas, were as fine as you'll get anyplace. And they were all Canadian. The whole bunch of them."

The experience made a deep impression on Pidgeon. He's now of the opinion that most of Canada's expatriate actors would jump at the chance to work in their homeland. "They would come, if they got a good story."

He offers as an example his co-star in Harry in Your Pocket, Quebec City-born Michael Sarrazin. "He'd come back in a minute and do a picture, if it had a good script. Anybody, any Canadian would.

"I'm going on my own feeling, and I'm an American citizen, but I still have that thing in my background. Canada is home.

"I like the whole setup, and I like working up here. I'd come back in a minute, if I liked the script. If I don't, I won't.

"I'm not going to do something I don't like. I'm too old for that now."

The above is a restored version of a Province interview by Michael Walsh originally published in 1973. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: There were so many things that we didn't get to discuss. I would like to have heard Walter Pidgeon's memories of playing Dr. Morbius (in the classic 1956 science-fiction film Forbidden Planet), in which he starred opposite fellow Canadian Leslie Nielsen, or of his role as Admiral Harriman Nelson, in the 1961 feature Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea. I would like to have heard his thoughts on the pop-culture coincidence that brought him to what some historians claim is the final resting place of his most notorious character. (It is believed that William Quantrill, the Confederate mass murderer Pidgeon played in Dark Command, survived the Civil War and escaped to Canada, where he lived until 1907 on Vancouver Island.) Harry in Your Pocket was his 112th theatrical feature. Pidgeon appeared in another three films, and many television productions, before his death two days after his 87th birthday in 1984. Despite his hope for more work in his homeland, none of those projects were shot in Canada.