Friday, February 4, 1977.

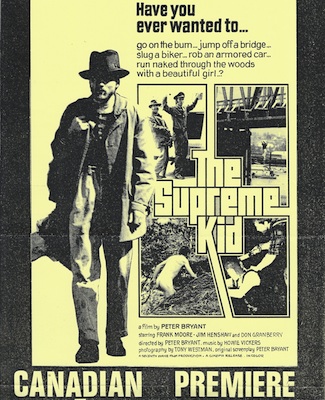

THE SUPREME KID. Music by Howie Vickers. Written, produced and directed by Peter Bryant. Running time: 90 minutes. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: occasional sex, frequent coarse language.

THE KID’S GOT PROBLEMS. He’s a drifter, a “king of the road” with no apparent skills, education or ambition. His name is Ruben (Frank Moore).

Last night, he went out and got high with an old wino. He spent the night in jail, where he was severely beaten for giving lip to a cop.

Today, he is badly bruised, hung over, angry and bitter. “I’d like to throw a bomb in a crowd,” he says, dimly articulating his general rage.

The Supreme Kid has problems. Billed as a comedy, director Peter Bryant’s first feature film is like a person who laughs without smiling. His tone is one of quiet desperation, his attitude one of despair.

Ruben and Wes (Jim Henshaw) are on the bum. Aside from the fact that they’re travelling together, we’re told nothing about them. From nowhere, they are going nowhere and that, in a nutshell, is the essential problem with their picture.

We pick them up fleeing from a farmhouse where Ruben has been bedding the farmer’s fat wife (Claudine Melgrave). They light, briefly, in a boarding house run by an old man named Moses (Tom Snelgrove).

There, they meet Wilbur (Don Granbery), a socially backward would-be thief. Ungainly, unattractive and unimaginative, Wilbur lives in a comic strip world where he daydreams about “the main chance.”

“Someday," he says, “I’m going for the big heist.”

Listening to Wilbur is like sitting in on a conversation in a skid-road beer parlour. Indeed, what Bryant is doing is making a movie about beer parlour people, presenting them without gloss, glamour or sentimentality.

The trouble is that neither Bryant’s people nor the things that happen to them are particularly interesting. The film’s incidents, like successive rounds at a beer bust, become less and less entertaining as they follow one upon the other.

The “big heist” happens more or less by accident. While Wilbur sits at home dreaming, Ruben and Wes casually rob an armoured truck, bury the loot and head up country to let things cool down.

Along the way the boys encounter Edward Schorr (Bill Reiter, a familiar voice from the CBC radio series Dr. Bundolo’s Pandemonium Medicine Show), the self-proclaimed “padre of the highway.”

They give aid to Luther Midruff (Terry David Mulligan, currently the host of CBC radio’s Great Canadian Gold Rush), an unmechanical motorist with a breakdown. They picnic with a motorcycle gang led by Jack the Biker (experimental film-maker Byron Black) and romp nude with an unnamed girl hitchhiker (Helen Shaver).

What Bryant fails to do is provide any sense of connectedness. There is no logical progression from here to there, from scene to scene or from event to event. The reels could be shown in virtually any order and the effect would remain the same.

The Supreme Kid, despite bright, original music from Howie Vickers, is a downer. It is a series of incidents without any strong narrative drive. Truth to tell, life among the down-and-outs is not much fun.

* * *

PETER BRYANT HAS HAD problems. The Supreme Kid is his first feature film (and, incidentally, the first feature to be directed by an alumnus of the Simon Fraser University Film Workshop). Started in February, 1974, it has just now [1977] made it into the theatres.Its current Vancouver engagement is its Canadian commercial premiere.

Shot in June and completed in December, 1974, it was scheduled for release in early 1975. Then the negative was damaged, and that held things up for some six months.

The hiatus gave most of his performers time to do other things. Helen Shaver want east and was featured opposite Cliff Robertson in Shoot (1976), a suspense thriller that arrived in Vancouver one week before The Supreme Kid.

Shaver will soon be seen in a supporting role in Alan King’s Who Has Seen the Wind [1977] and will star opposite Robert Vaughn and Christopher Lee in the science-fiction film Alien Encounter [1977].

During the long wait, Jim Henshaw starred in the features Monkeys in the Attic (1974) and Lions for Breakfast (1975), the former an experimental item as yet unseen in Vancouver. Don Granbery was seen terrorizing Brenda Vaccaro in the Bill Fruet film, Death Weekend (1976).

Also making an impact is Frank Moore, winner last October of an acting Etrog at the Canadian Film Awards for his performance in Joyce Weiland’s 1976 feature, The Far Shore. In November, he co-starred with Marilyn Chambers in David Cronenberg’s latest horrorama, Rabid.

Before its Vancouver premier, The Supreme Kid played a number of international film festivals. It was particularly well received in Eastern Europe. A total lack of political propagandizing, coupled with its gloomy view of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, seems to have struck a responsive chord among Czechoslovakian audiences.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1977. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Tony Westman remembers The Supreme Kid. A graduate of SFU’s original Film Workshop, he was Peter Bryant’s cinematographer on what was their first feature film. “Oh those good old days of great aspirations,” he wrote to me Saturday morning (January 28) in an email. Tony Westman was a key player in the creation of what came to be called “Hollywood North,” an aspirational moment that is being celebrated tonight (January 30) at the Pacific Cinémathèque. The fourth program in the third Image Before Us series curated by Harry Killas, it pairs the debut features of Larry Kent (1963’s The Bitter Ash) and Peter Bryant. Introducing the movies and providing historical context will be my old Province newspaper colleague David Spaner, author of the 2003 book, Dreaming in the Rain: How Vancouver Became Hollywood North by Northwest. Working to preserve the memory of “those good old days,” Killas and Spaner deserve our respect and appreciation. Nor can we forget former Province writer Mike Gasher, who was inspired by the achievements of Westman’s generation to write 2002’s Hollywood North: The Feature Film Industry in British Columbia. And, in 2001, the Vancouver Sun’s movie critic Katherine Monk published Weird Sex and Snowshoes: And Other Canadian Film Phenomena. Their books have taken their place on a growing list of B.C. film histories, all of them in debt to the pioneering work of the great Colin Browne (1979’s Motion Picture Production in British Columbia, 1898-1940) and B.C. provincial archivist Dennis J. Duffy (Camera West: British Columbia on Film, 1941-1965; published 1986).