June 6, 1984.

FORTY YEARS AGO TODAY [June 6, 1944], Canadian, British and American forces landed in Normandy. Young men waded ashore with crusaders' zeal, a sense of purposefulness that had been instilled in them by a series of official films called Why We Fight.

The director of those films, Major Frank Capra, was not a professional propagandist. A Hollywood director, he had been drafted by American Chief of Staff General George Marshall to "explain to our boys in the Army why we are fighting and the principles for which we are fighting." [italics in the original]

Capra was not completely comfortable in the role. Although he did his job magnificently, he remained uneasy about official filmmaking until 1945.

"It was not until they showed us the stuff that we got at Dachau," Capra told Bill Moyers in a recent interview, "(the footage) that George Stevens photographed . . . (that) it actually impinged itself on the mind. The horror, horror of this whole thing was real. Then we believed."

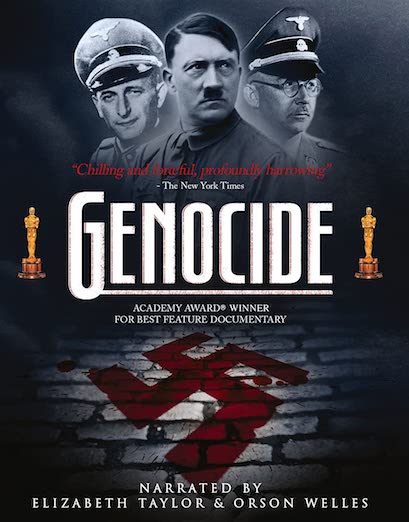

Monday evening [June 6, 1984], a capacity crowd gathered at the Ridge theatre for the benefit premiere of Genocide, a feature-length documentary recalling "the horror." An uncompromising, entirely necessary history lesson, it not only shows us why we fought, but what.

On the anniversary of D-Day, these are things worth remembering. Our war, Capra told Moyers, was not against the Germans, the Italians or the Japanese, but against "the hate (and) the haters.”

Soon to be released both theatrically and on videotape, Genocide will be the subject of a full review at that time.

Wednesday, June 20, 1984.

MOST OF THEM KNEW the word "sadism.”

Although the works of the infamous Marquis de Sade would not be generally available until the 1960s, his name was part of the language, a synonym for unthinkable cruelty.

Some, perhaps, had read Joseph Conrad. They may have thought about that title, Heart of Darkness, about the evil that Mr. Kurtz encountered within himself, about an unspeakable, unforgettable "horror.”

Nothing in language or literature, nothing in their experience or training, nothing had prepared the young men of the Allied liberating armies for the soul-shrivelling reality of the Nazi death camps. If man’s best works honour God, then these mass-murder factories reeked with the presence of Satan.

It happened. Its perpetrators called it "the final solution to the Jewish question.” Its victims remember it as "the Holocaust."

The liberating troops will never forget what they saw. Those of us who have seen the newsreel footage, or heard the normally even voice of Edward R. Murrow vibrate with anger as he described Buchenwald, need no reminders.

There is however, a new generation for whom all of this is pre-history. Like the young soldiers, they find it hard to believe in so profound a nightmare, and it is to them that the sad, twisted minds among us address their pathetic conspiracy theories, their ugly personal resentments and racial hatreds.

The innocents need to know the truth about hate. It is for them that the Simon Wiesenthal Centre has produced Genocide, a visceral yet fact-filled feature documentary chronicling the Hitlerian attempt to exterminate European Jewry.

Cinematically, British-born director Arnold Schwartzman has pulled out all the stops to make a visually riveting, technically superior motion picture. Animation, multi-screen imagery and a full symphonic score composed and conducted by Elmer Bernstein all contribute to its big-screen watchability.

Narration duties are shared by Orson Welles, who voices the historical overview, and Elizabeth Taylor, who reads from the written accounts of victims and survivors. Together, they tell a story that goes beyond mere facts and figures to count the incredible human cost.

Unsettling and unforgiving, this Academy Award-winning feature is, nonetheless, necessary. Genocide shows us mankind at its worst in the humanitarian hope that knowledge of such horrors can prevent them from ever coming again.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1984. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: The horrors of the Nazi Holocaust were real. Sadly, they were hardly unique. Genocides — defined as the deliberate and systematic destruction in whole or in part of an ethnic, racial, religious or national group — have been a part of the historical record since the Romans laid waste to Carthage in the Third Punic War (149-146 BC). The word has been used to describe the slaughter of native peoples in the Congo (under the rule of Belgium’s Leopold II), and in North America ever since the arrival of Christopher Columbus. As recently as 2019, Canada’s National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls found that this nation has and continues to engage in “race-based genocide.”

Let me repeat: The horrors of the Nazi Holocaust were real. I first became aware of them in 1959, when the CBS-TV series Playhouse 90 broadcast writer Abby Mann’s courtroom drama Judgment at Nuremberg. My personal outrage only grew when I saw director Stanley Kramer’s powerful 1961 screen adaptation, and I cried as I listened to Spencer Tracy’s Judge Dan Haywood declare that “this is what we stand for: justice, truth . . . and the value of a single human being.” Those feelings were still strong within me when I reviewed director Arnold Schwartzman’s Genocide in 1984, a time when Holocaust denial was much in the news. (In Canada, an Alberta high school teacher named James Keegstra was convicted of hate speech for telling his students that the Holocaust was a fraud.)

The horrors of the Nazi Holocaust were real. Around the turn of the century, though, I became aware of a related concern among credible scholars. In 2000, historian and political scientist Norman Finkelstein published The Holocaust Industry: Reflections on the Exploitation of Jewish Suffering. A Jew and the son of Holocaust survivors, he documented the dark side of genocide memorials, calling attention to the fact that there were individuals and organizations exploiting them for political and financial advantage. He was outraged at what he considered a corruption of Jewish culture and the authentic memory of the Holocaust. According to Finkelstein, one organization profiting from the industry is the Los Angeles-based Simon Wiesenthal Center (or, as he calls it, the “Center for Holocaust Hucksterism”). In 2000, Britain’s Guardian newspaper quoted his comment that "The Centre is renowned for its 'Dachau-meets-Disneyland' museum exhibits and the successful use of sensationalistic scare tactics for fund-raising."

Here’s where it gets complicated. New-York-born Rabbi Marvin Hier, who co-wrote and co-produced the film Genocide for a company called Moriah Films, founded the Simon Wiesenthal Centre in 1977. Moriah Films is a wholly-owned subsidiary of the SWC, an organization that includes in its mission promotion of the interests of the State of Israel. Step one is to tell the truth: the horrors of the Nazi Holocaust were real. Step two is to promote a lie, the one that conflates Judaism (a 4,000-year-old religion) with Zionism (a late 19th century political ideology). Confuse the two, and legitimate critics of Zionist Israel’s apartheid policies (such as Finkelstein) can be dismissed as “anti-semites.” The good news is that a new generation of American Jews (among them Crisis of Zionism author Peter Beinart) are refusing to buy the lie.

And, finally, the horrors of the Nazi Holocaust were real. German director Heinz Schirk had no doubt of it when he made his 1984 docudrama Die Wannseekonferenz (The Wannsee Conference), the story of the 1942 meeting that set “the final solution” in motion.