Saturday, May 28, 1977.

GAMES OF THE XXI OLYMPIAD, MONTREAL 1976. Music by André Gagnon, Art Phillips, Vic Vogel. Directed by Jean Beaudin, Marcel Carrière and Georges Dufaux under the overall direction of Jean-Claude Labrecque. Running time: 119 minutes.

THEY BLEW IT. The National Film Board, commissioned to produce the official commemorative film of the 1976 Summer Olympics, deployed a crew of 168 and shot nearly 60 miles (or 200 hours) of film.

The result celebrates not so much the Olympic ideal as the Film Board's own eccentricity.

There's no denying that director Jean-Claude Lebrecque and his three associates (Jean Beaudin, Marcel Carrière and Georges Dufaux) had the courage of their convictions. For this project, though, their convictions were all wrong.

Their film, Games of the XXI Olympiad, Montreal 1976, makes two disastrous assumptions. One is that the saturation news coverage accorded that event last summer left everyone in the world familiar with their subject.

The other assumption is that “cinéma direct,” the Board's favourite short-subject film style, is just as effective in feature length. Unfortunately, their feature ends up looking like a series of shorts that have been spliced together.

The whole is considerably less than the sum of its parts.

What Labrecque’s team has attempted to do is show us the Olympics through the eyes of the athletes. Seven months before the games opened, the filmmakers chose a number of contenders and assigned camera crews to dog their every step.

In each case, they hoped to capture an event from the competitor's point of view. Some would win, others lose. The mosaic was supposed to provide us with a close-up, human experience, one that would reveal, according to an NFB brochure, “what the television cameras never showed.”

It was an interesting, if unoriginal, idea. The trouble is that it is the sort of idea best suited to documentaries about high school track meets, or intelligently scripted fictional features, such as director Don Shebib’s recent [1976] Second Wind.

The Olympics are rather more than that. Though they may aspire to athletic asceticism, we all know that the modern games are a quadrennial cockpit of political and commercial competition. The distinctive nature of each meet is provided by the location and prevailing conditions in the world community.

Labrecque would probably disagree. He is less interested in capturing the scent of today than the timeless smell of sweat socks. His approach lavishes more attention on pre-event tensions and post-event gasping for breath than on the competitions themselves.

Narration is kept to an absolute minimum. The result is one of the least informative “documentaries” that I’ve ever seen.

Having ignored the Games when they were played, I arrived at the preview screening knowing next to nothing about the 21st Summer Olympics. The only name I recognized was that of gymnast Nadia Comăneci, the amazing Romanian kid who made it on to all of the newsmagazine covers.

Two hours later, I still knew next to nothing. Labrecque's fatiguing film made me really aware of only one other name, that of the showboat American track star, Bruce Jenner. The rest is still a matter of either indifference or confusion.

To take just one example: who was that blonde that associate director Dufaux’s cameramen kept picking out during the Jenner events? Although she was important enough to be photographed, like so many faces in the film she is never identified.

Well, it turns out that she was Jenner’s wife, Chrystie. My colleague Clancy Loranger, who covered the Games in Montreal last summer, recognized her right away. The veteran sports writer had to tell me something the filmmakers assumed we all already knew.

If you know, you'll know. Wednesday [May 25, 1977] in his column, Clancy caught the spirit of the thing nicely when he wrote “just among us sports buffs, I rated it about three goose bumps.”

For those who were there, either in person or through the daily coverage, Labrecque’s close-up diary will bring it all back. For those who weren’t, Games of the XXI Olympiad, Montreal 1976 is about as interesting as your brother-in-law’s home movies of his summer vacation.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1977. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Sports writer Clancy Loranger was already a Vancouver newspaper legend when I arrived at The Province in 1969. His 47-year career started in 1939, and he’d been a full-time columnist since 1965. On his retirement in 1986, the City named a street in his honour: Clancy Loranger Way, which just happened to be the road one took to the Nat Bailey (baseball) Stadium. Inducted into the B.C. Sports Hall of Fame in 2003, the genial Loranger died in 2010 at the age of 89.

As the above notice makes clear, I’m not a corporate sports fan. In the introduction to my review of 1979’s Goldengirl, I say that the modern Olympics are all about politics and advertising revenues. The subsequent career of decathalon gold medalist Bruce Jenner, the athlete that I call a “showboat” in the review above, is living proof of the commercial focus. From 1976 to 2014, he traded on his fame as “world’s greatest athlete,” working as a breakfast cereal spokesmodel and TV actor. He ended his nine-year marriage to Chrystie Crownover in 1981. He then married and divorced two more women — actress and beauty queen Linda Thompson (1981-1985) and professional celebrity Kristen Kardashian (1991-2014) — before deciding that he preferred being his own woman. In April 2015, Jenner reintroduced himself to the world as Caitlyn, a trans woman. Famous again, he told his story in an eight-part 2015 TV miniseries, I Am Cait.

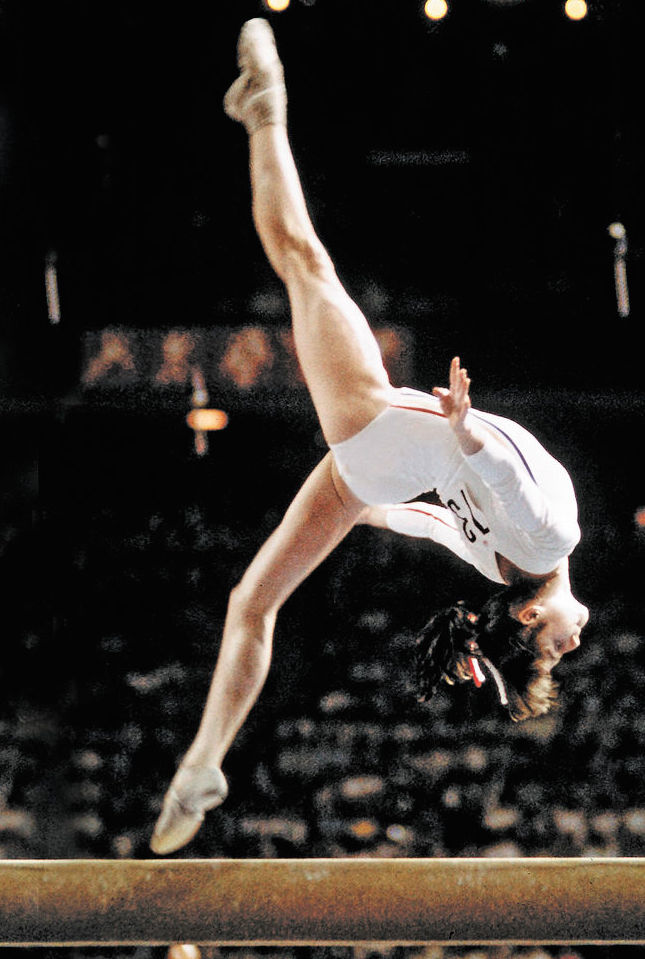

As for the politics, consider Nadia Comăneci, the darling of the Montreal Games. The 14-year-old gymnast’s seven perfect tens, along with her three gold medals, a bronze and a silver, made her the cover subject of Time, Newsweek and Sports Illustrated, all in the same week. Because she represented a Soviet bloc country, she was immediately named a “Hero of Socialist Labour.” Because she was a minor, she had no control over the decisions made for her, and was in a very real sense the property of the Romanian state, one ruled since the mid-1960s by Communist Party leader Nicolae Ceauşescu. Details of Nadia’s teen years are in some dispute. Her mother has said that she was raped by Ceauşescu’s vile son Nicu in 1979; Nadia has denied the allegation.

What’s not in dispute are her athletic achievements, including a further two gold medal wins at the 1980 Moscow Olympics. In 1981, her lifelong coaches Béla and Márta Károlyi defected to the U.S. during an exhibition tour, an action that drastically changed Nadia’s situation in her homeland. “I started to feel like a prisoner,” she said later. “In reality, I’d always been one.” She made her own escape in 1989, a few weeks before the bloody revolution that toppled the Ceauşescu régime. For a time, she lived in Montreal, doing sports promotions and occasionally modelling. In the early 1990s, she connected with U.S. Olympic gymnast Bart Conner, and they married in 1996. The couple live in Norman, Oklahoma, but they are currently in Rio de Janeiro for the 2016 Games, where Nadia Comăneci is celebrating the 40th anniversary of her ‘perfect 10’.