Saturday, April 10, 1976.

THE BAD NEWS BEARS. Written by Bill Lancaster. Music by Jerry Fielding. Directed by Michael Ritchie. Running time: 102 minutes. General entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning to parents: coarse language throughout.

TIME OUT. CONSIDER FOR A moment these inspirational words from American sportswriter Grantland Rice:

When the One Great Scorer comes to write against your name —

He marks — not that you won or lost — but how you played the game.

Time in. The Bad News Bears is a movie about sportsmanship, 1970s style. It examines not the quaint, poetic ethos of Rice, but the more pragmatic philosophy espoused by the likes of Vince Lombardi, a philosophy summed up in the single word: Win!

Like Robert Aldrich's 1974 football epic The Longest Yard, The Bad News Bears is a comedy about an unwilling coach drafted into the job of making winners out of a misfit team. Like Aldrich's film it is sharp, biting and terrifically funny.

Here, though, the game is baseball. Unlike The Longest Yard, which was violent, adult-oriented and Mature-rated, the Bears story is fine family fare that's General-rated (with a coarse language warning). Its setting is the world of the suburban Little League.

The unwilling coach is Morris Buttermaker (Walter Matthau), a one-time minor-league pitcher who now makes beer money as a swimming pool cleaner. A seedy, lovably boozy version of Matthau's Odd Couple character, Buttermaker takes on the Little League job for the extra income.

The team is the idea of an image-conscious politician, an unctuous city councilman named Bob Whitewood (Ben Piazza). He has fought a court case to win underprivileged kids the right to play in the tony North Valley Sandlot League, and is determined to see a few of them do so.

Assigned the name "Bears," the new team is fiercely resented by the upper-crust parents who regard the Little League as an extension of their own country club society. Roy Turner (Vic Morrow), coach of the championship Yankees, is especially scornful.

The Bears, a group that includes a compulsive eater, a pugnacious squirt, a brainy bookworm, a very slow learner, a black and a pair of Chicanos who speak no English, make a disastrous debut. The game is called off at the end of the first half inning.

The score is 26-0 in favour of the Yankees. Everybody says the Bears should quit.

Everybody, that is, except coach Buttermaker. His pride hurts worse than his hangover. In the best tradition of the movies, he decides to mould his ungainly lot into a winning team. He's got a few tricks up his unwashed, slightly frayed sleeve.

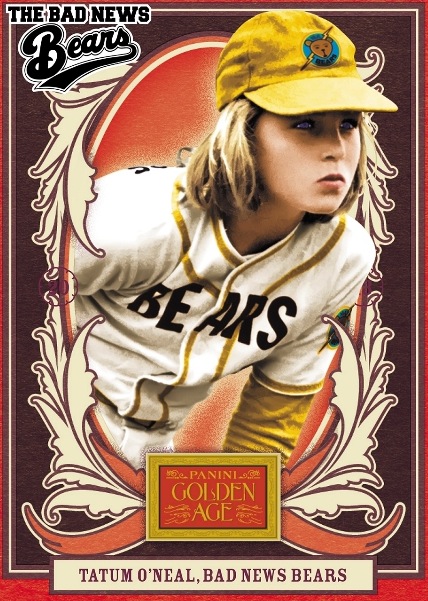

His first trick is 12-year-old Amanda Whurlitzer (Tatum O'Neal), a little girl he taught to pitch a few years earlier during a romantic involvement with her mother.

His second trick is Kelly Leak (Jackie Earle Haley), a local juvenile delinquent whose skills on the infield and in the batter's box are phenomenal. Revitalized, the team is sure to make the playoffs.

Time out. So far as I know, there is no critical cult devoted to the works of director Michael Ritchie. It's time that someone started one. With the release of The Bad News Bears, Ritchie has five theatrical films to his credit, all of them excellent.

In his movies Ritchie, 36, has defined for himself a definite subject area and honed a distinctive approach. His subject is contemporary competitive institutions. His approach is slyly satirical.

A former TV director, he broke into theatrical movie-making in 1969 with Downhill Racer, a ski film that starred Gene Hackman and Robert Redford.

Redford worked with him again in 1972, playing the part of a successfully packaged political contender in The Candidate. Hackman returned to co-star with Lee Marvin in Ritchie's Prime Cut, a slice-of-life look at organized crime. Last year [1975], the director turned his attention to beauty contests with the film Smile.

A brilliant craftsman, his well-thought-out films are full of insight and genuine social commentary. According to the director, though, what he really wants to do is make people laugh.

In 1972, Ritchie was in Vancouver promoting The Candidate. "You know what I'd really like to see?" he said. "A headline on your story that said 'The Candidate — a laugh riot.' " (He didn't see it. When the review appeared, the headline read "An instant classic".)

This time out Michael Ritchie deserves to get his wish. How about it, Mr. Headline Writer? I'll say it in the story so that you can quote it in the head: Bad News Bears — a laugh riot.

Time in. It's the Bears vs. the Yankees for the league championship. It's the culmination of a season that has given lip service to Rice while heeding the gospel according to Lombardi. The kids are becoming more than a little numbed by the adults and their fierce need to see their children win.

In a tough — remember that coarse language warning?— pep talk, coach Buttermaker puts down his beer can long enough to lay it on the line.

"You've been laughed at and crapped on all season. Now you've got a chance to rub it in their faces. I mean, don't you want to beat those bastards?"

This is the moment of truth, something that Ritchie has been underscoring all along with his use of composer Jerry Fielding's adaptations of Bizet's Les Toreadors theme during the game sequences. He builds to it so effectively that his final inning has audience members on the edge of their seats and cheering.

When you see that in a movie house, amid the laughter and even a few tears, you know you're looking at a home-run hit. The Bad News Bears is good news entertainment.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1976. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: It was tough to be a kid in the 1970s, just one of the many things that director Michael Ritchie showed us in The Bad News Bears. His picture's most enduring character, Amanda Whurlitzer, embodied the street-smart toughness and social isolation of what has come to be known as Generation X. As it turned out, actress Tatum O'Neal became something of case study in the roller coaster ride Gen-Xers have experienced. The daughter of screen actor Ryan O'Neal, she made her performing debut starring with him in director Peter Bogdanovich's Paper Moon (1973). At the age of 10, she became the youngest winner of an Academy Award in a competitive category — the six-year-old Shirley Temple's 1935 Oscar was an "honorary award" — a distinction O'Neal retains to this day. Her second picture, The Bad News Bears, was the last big hit of her career. In her 2004 autobiography, A Paper Life, she describes her father's drug problems and alleges that his drug dealer molested her when she was 12. Her personal life — including teenaged dates with singer Michael Jackson, an eight-year marriage to tennis star John McEnroe and a recent four months spent "dating" Rosie O'Donnell — has been the stuff of tabloid headlines for years. It's been reported that she's struggled with her own drug habit since the age of 14, which may account for the lack of acting opportunities available to her after the box office failure of her third feature, Bogdanovich's 1976 comedy about silent-era filmmaking, Nickleodeon. Among her 17 subsequent features are the Canadian tax-shelter drama, Circle of Two (1981), for which she visited Toronto to co-star with Richard Burton, and the made-in-Vancouver Certain Fury (1985), a remake of 1958's The Defiant Ones, that features O'Neal on the run with Irene Cara. She reunited with Bogdanovich in mid-2013 to play a cameo role in his troubled screwball comedy She's Funny that Way, a picture finally given a limited release in 2015 before going to video on demand. Tatum O'Neal celebrates her 52nd birthday today (November 5).