Thursday, November 6, 1975.

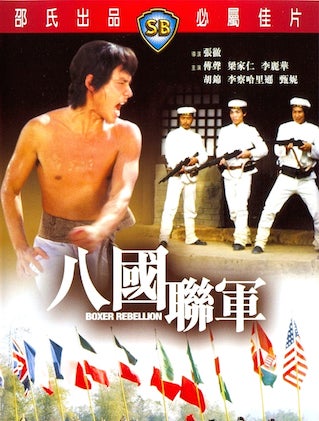

BOXER REBELLION (Ba guo lian jun). Co-written by Kuang Ni. Music by Yung-Yu Chen. Co-written and directed by Chang Cheh. Running time: 137 minutes. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning “many violent scenes.” In Mandarin with English subtitles.

THERE ARE AT LEAST three ways to view Boxer Rebellion, the epic-length historical drama currently playing Hastings Street's Shaw Theatre. One is to see it as a significant step in the evolution of Chinese film.

Another is to see it as a belated dramatic response to the non-Chinese cinema's version of Chinese history (most specifically, Nicholas Ray's multimillion-dollar 1963 feature 55 Days at Peking). On the whole, though, it is probably best viewed as rousing action entertainment.

Nearly 2½ hours long — there is an intermission — Boxer Rebellion suggests that its producer-director, Chang Cheh, is well on his way to becoming the Far Eastern Cecil B. De Mille. Like De Mille, Chang shows a marked preference for grand themes and national heroes. Like De Mille, he enjoys mounting super-productions.

Until now, Chang was best known to Western audiences for his Shao Lin trilogy, a cycle of films dealing with the Manchurian subjugation of 17th-century Canton and the men who resisted it.

Here, however, he focuses on a pivotal event in modern Chinese history, 1900's Boxer uprising.

An inglorious event all around, it was dealt with rather superficially in the American-made 55 Days at Peking (1963). The story, often seen on TV, begins with a group of European diplomats, led by the British ambassador played by David Niven, protesting the murder of Christian missionaries.

Responsible for these outrages is a fanatical group whose members are known as Boxers. Secretly encouraged by China's Dowager Empress, they eventually turn their wrath on the foreign legations in Peking.

For 55 days the siege continues. At times it seems that the only thing standing between the 3,000 innocent foreign civilians and the bloodthirsty Boxers is Niven's stiff upper lip and U.S. Marine Major Charlton Heston's jutting jaw. At the end, an Allied relief force arrives, the flags of Britain, France, Germany, Japan, Russia, Spain, Italy, Belgium, Holland, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the U.S.A. catching the same breeze.

The same flags are seen in Chang’s version, but the audience is less inclined to cheer their appearance. His film, though not much more profound, does range further than Ray's, and in doing so involves more factions, more characters and, ultimately, more tragedy.

Chang's story begins in the same opulent court, a palace that seems to have been untouched by reality for more than a millennium. Tz'u Hsi (Li Li-hua), the Empress Dowager, dislikes foreigners. If the Boxers give them trouble, so be it.

In the countryside, things are considerably less calm. Chang shows us a national bureaucracy that is serving the interests, not of its nationals, but of foreign speculators. Little wonder, then, that young men by the hundreds are attracted to any group that promises to take action.

Indeed, the Boxer leader, a charlatan named Li Chung-ching (Wang Lung-wei), promises even more. His magic will make the Boxer armies invulnerable.

His proof? Blades do not even break the skin of patriot Chang Chen-chiang (Tang Yen-tsan).

It's true. But at least three recruits, Shuai Feng-yun, Chen Chang and Tseng Hsien-han (played by Shao Lin series regulars Chi Kuan-chun, Liang Chia-jen and Alexander Fu Sheng), are more impressed with the fighter's iron-skin kung-fu technique than any of Master Li's magic.

Privately, the Boxer hero himself admits that magic is nonsense. He goes along with it only because it swells the Boxer ranks.

Shuai is dubious. He would rather that they all follow the moderate Dr. Sun Yat-Sen, but decides that he will go along as well.

If Ray was willing to treat his Chinese hordes as stereotypes, Chang is just as willing to gloss over the differences among the "foreign devils." All are depicted as eager oppressors of the Chinese, cartoon capitalists and drooling, militaristic sadists.

Among the Chinese, though, he finds a variety of powerful emotions — among them opportunism, personal vendetta, patriotism, religious fanaticism, mass hysteria and even youthful boredom — all of which come together to create the nationalist explosion.

Ray's film ended with the lifting of the siege and with Heston’s character riding off into the sunset. Chang's story, on the other hand, is only half over.

Once installed in the capital, the Allied relief force, under German field marshal Alfred Graf Von Waldersee (Richard Harrison) effects "Operation Punishment" and heads roll. Literally.

Here, Chang comes up with a plot twist that the history books seem to have missed, but that De Mille would have gloried in. Waldersee was once in love with a well-travelled courtesan named Sai Chin Hua (Hu Chin).

The great love of patriot Shuai's life, meanwhile, is the country girl who left town to become — wait for it — the same mistress Sai.

Passion, history, adventure, romance. All of it done with the added attraction of kung-fu battles choreographed with Chang's usual flair.

Nor is Boxer Rebellion an isolated instance of epic on the Hong Kong studio production sheets. Chang now is working on a film called Marco Polo, a story that reunites Boxer stars Fu Sheng, Harrison and Chi Kuan-chun.

Next month [December, 1975], director Li Han-hsiang's The Empress Dowager, reportedly the most expensive project ever mounted by the Shaw Brothers, will be released in Vancouver.

Nationalistic epic, long a part of the American film scene, is setting down roots in Hong Kong. As long as it remains action-packed, colourful and only peripherally polemical, it should do well by the local filmgoers.

* * *

BARE-KNUCKLE HISTORY: They could have taken a name like "the Chinese Republicans” or "National Liberation Army." But, like the Black Power advocates of the 1960s, their symbol was a closed fist. And, because they were determined to fight together, they decided to call their organization The Society of Harmonious Fists.Their enemies, all foreigners living in China, were too busy fighting them to engage in scholarly translation. In English, they were called, simply, "Boxers."

The proper name is spoken in Mandarin on the soundtrack of the film Boxer Rebellion. The subtitles, however, retain the historical mistake and the translation remains "Boxers."

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1975. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: The Boxers lost the fight, but it can be argued that they eventually won their war. Their rebellion is often cited as a death blow to dynastic rule in China. In 1912, Dr. Sun Yat-Sen (referred to in the movie) became the provisional president of the new Republic of China. Sun’s Nationalist Party was opposed by a Communist Party, founded in 1921 in the wake of the 1917 Russian Revolution. The 20th century would be a tumultuous time for the world’s most populous nation, a country much abused by the 19th century’s many colonial empires.

When civil war between Communist and Nationalist forces broke out in 1927, the names “Mao Tse-tung” and “Chiang Kai-shek” were added to the style guides used in U.S. and Canadian newsrooms. That conflict was still going on when the first act of the Second World War, Japan’s invasion of China, occurred in July, 1937. When the war widened to include Europe and the United States, China was acknowledged as “a great power” ally in the fight against fascism. In 1949, four years after Japan’s surrender, Mao’s forces prevailed in the civil war and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was founded. For years thereafter, the American political class would argue the question of “who lost China?” Movies like 1963’s 55 Days at Peking would maintain the tradition of infantilizing a nation that had made the choice not to accept the U.S. as the essential superpower.

One source of the Boxers’ anger was the fact that they knew they were part of a civilization with more than 2,000 years of history and accomplishment, a civilization that was getting no respect from the newly industrialized West. Against all the odds, they were determined to make China great again. Not to put too fine a point on it, the PRC has come a long way in 69 years. Late last year, Britain’s Economist newsmagazine (a publication that’s been covering international politics since the opium wars) featured China’s President Xi Jinping on its cover, identifying him as “The world’s most powerful man.” He leads a nation poised to replace the United States as the world’s largest economy. The story continues . . .