Tuesday, October 30, 1990.

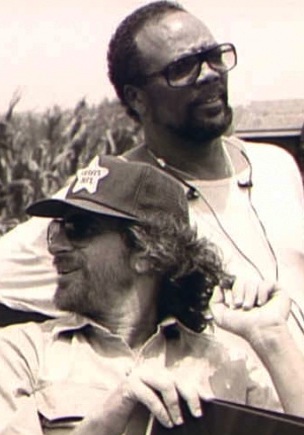

LISTEN UP: THE LIVES OF QUINCY JONES. Music by Quincy Jones. Written and directed by Ellen Weissbrod. Running time: 115 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: occasional very coarse language and violence.

THE SUBJECT IS PAIN. "I just kept screaming, 'Help! Help me!"'

In 1974, composer Quincy Jones collapsed.

"It was an aneurysm," he tells us in Listen Up, a documentary feature examining The Lives of Quincy Jones.

"The brain was so damaged and swollen, if they went in then it would have just jumped straight out of my head . . ."

At this point, I'm in pain.

Too many blurry videotaped images and too much jump-cutting has given me a nasty headache.

In principle, I'm in sympathy with producer Courtney Sale Ross and director Ellen Weissbrod. Jones is a terrific subject, his "lives" prime documentary material.

Born in Chicago, raised in Washington state, the man and his music are part of the modern American dynamic. To date [1990], Jones's honours include a 1977 Emmy Award (for the TV miniseries Roots), 75 Grammy Award nominations (with 25 wins), and seven Oscar nominations. His story has all the elements of drama, conflict, genius and celebrity that inspire biographers.

Ross, a Skidmore graduate with roots in the New York fine arts community, "didn't want Listen Up to be a traditional documentary." The creative force behind the 1984 PBS television series Strokes of Genius, she presents her Jones profile as "a collage of memories, sounds and intimate interviews . . . a rousing showcase of popular music, a living history of black America, a revealing glimpse into the psyche of an artist and a modern story of inspiration."

Back in the 1960s, we called this sort of thing "McLuhanesque." When it became obvious that attempts to use the technique were producing more confusion than comprehension, it was abandoned as a means of communicating information.

Artists, experimental filmmakers and other government-grant recipients still make such impressionistic "pieces" to maintain their avant-garde status.

What would once have been labelled psychedelic now is "kaleidoscopic." How else to describe the work's so-called associative structure?

"We wanted to show how the past is always with you in the present," says Weissbrod, "and how things in the present can segue into your past."

Perhaps if Ross and Weissbrod had used more actual film or better quality videotape, I'd be more in tune with their holistic synergy.

As it is, their trippy approach induced not an understanding of Jones, but a selection of physical symptoms that eventually included a knot of nausea in the pit of my stomach.

Listen Up: The Lives of Quincy Jones looks less like a tribute to a great artist than a self-indulgent, over-produced film school project.

* * *

LISTEN LISTINGS — Among the folk contributing their impressions of Quincy Jones during on-screen interviews are film directors for whom he composed movie scores, including Sidney Lumet (The Pawnbroker; 1964), Richard Brooks (In Cold Blood; 1967) and Steven Spielberg (The Color Purple; 1985).Also appearing are musicians Ray Charles, Miles Davis, Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Lionel Hampton, Frank Sinatra, Barbra Streisand and Sarah Vaughan. Michael Jackson spoke to the filmmakers but refused to appear on camera. We hear his voice. Or maybe it's Rich Little.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1990. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Quincy Jones, who celebrated his 83rd birthday on March 14, may have cut back on his compositional work load, but he's still able to generate headlines. Asked to present the 2016 Academy Award for best original score, he said he'd like five minutes of show time to speak "on the lack of diversity" or he wouldn't take part in the broadcast. Apparently, he changed his mind. The seven-time Oscar nominee showed up and, before presenting the award to Italy's Ennio Morricone, recalled working with Steven Speilberg on The Color Purple.

Listen Up was Ellen Weissbrod's debut as a documentary director. Her subsequent career includes much television work and the highly watchable 2010 feature A Woman Like That, an examination of the life and career of Artemisia Gentileschi, the 17th-century Italian painter who is both renowned and notorious in art history.