Thursday, July 17, 1980

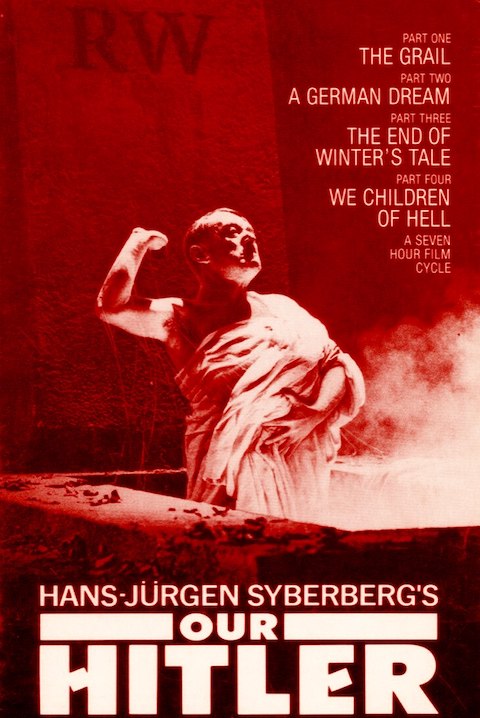

DER GRAL (Our Hitler). Written and directed by Hans-Jürgen Syberberg. In four parts: Hitler, A Film from Germany, with a running time of 90 minutes; A German Dream, 120 minutes; The End of a Winter's Tale, 90 minutes; and We Children of Hell, 100 minutes. Total running time: 400 minutes. Mature entertainment with no B.C. Classifier’s warning. In German with English subtitles.

NONE OF US KNEW quite what to expect. The feature was neither a documentary nor a conventional drama. All we really knew about Our Hitler was that it ran 400 minutes and would take all day to see.

It was enough to attract a capacity crowd to the Varsity Theatre Sunday afternoon. As it turned out, director Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s film was an audio-visual essay, a contemplation of myth, media and our fascination with fascism.

Academic rather than outrageous, his picture attempts to provoke thought and stimulate discussion. What follows are some thoughts provoked by his six-hour, 40-minute opus.

* * *

Why spend an entire day looking at a movie?Why not?

Director Peter Boganovich considered a similar question in a November 1968 interview. “A whole school of critics think they like movies,” he told Marlin Rubin. “But they don’t.

"They think it's all very nice to like films — within limits. You can't have a passion for them because, after all, it's still a bit juvenile to sit in a movie theatre for six hours. Something not quite right about it.

"However, people who read books for hours are eggheads, geniuses. It's really a kind of Victorian anti-movie theory."

* * *

Our Hitler is divided into four sections, each one a separate feature with its own title. Part One is called Hitler, A Film from Germany, and it sets forth the thesis that Syberberg will examine throughout the whole work."This show," he tells us, ''is about a man who is guilty of everything.” Most of all, he is guilty of failure. Like Milton's fallen angel Satan, Hitler promised his followers paradise, and then led them to hell.

"Only the defeat of our arms made us turn away from him," Syberberg reminds his German audience, "not reason.”

This is true, the director contends, because Hitler is a force "within us.” Both film and Hitler are defined as "projections of our inner thoughts.” For Syberberg, Hitler is a metaphor and the words “Hitler” and "film" are synonyms. His Hitler is a film from Germany.

Film references abound. A scene representing Hitler’s nativity resembles a Christmas creche except for the fact that the figures standing about are all characters out of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

A man with the letter “M” chalked on the back of his coat turns towards us. The camera pulls back to reveal a Nazi brownshirt, who proceeds to play Peter Lorre's final scene (“I can’t help myself. I haven't any control . . .") from Fritz Lang’s classic thriller, M.

Then, in what appears to be a tangential tirade, Syberberg rails against the American and Soviet film establishments for their crimes against the movies. The capitalists destroyed the works of Erich von Stroheim, he says. The communists censored Sergei Eisenstein.

* * *

Francis Ford Coppola wants to change the face of the cinema. The director of the ultimate anti-war movie, Apocalypse Now, Coppola feels that neither the audience nor the filmmaker should be bound by conventional ideas of feature length or content.A former film student, Coppola knows the story of emigré artist von Stroheim and his losing battle with the Hollywood studio system. Given total control of a film project in 1923, the autocratic Austrian went out and shot an eight-hour movie.

The studio wasn't interested. Writing von Stroheim off as a nut case, Louis B. Mayer ordered his picture cut down to a length more appropriate for commercial release. Premiered in 1924, Greed ran 112 minutes, and went into the history books as von Stroheim's "mutilated masterpiece."

Benefiting, perhaps, from the Austrian’s experience, Coppola learned his way around the film business and, when his chance came, he seized it. Coppola will go down in film history as the director who managed to make a commercially successful six-hour feature.

The Godfather, at 177 minutes, and The Godfather, Part Two, at 200 minutes, are a single work. Each is the winner of a best picture Academy Award, and together they affirm Coppola's position as a major breakthrough artist.

Not surprisingly, it is Coppola who is sponsoring Our Hitler in North America. Omni-Zoetrope, his San Francisco-based production company, is responsible for releasing the picture, and insisting that it be played at the length that it was filmed.

* * *

Our Hitler, Part Two, is called A German Dream. Here we see Hitler rise from the grave of Richard Wagner and inform us that he is the embodiment of our dreams.We meet a collection of people who lived their lives either for Hitler or through him. A pseudo-scientist explains his World Ice Theory, and the concept of the master race. Another tells us that "Hitler is not dead. He lives in the universe,” and then asserts that Hitler was rescued from the ruins of Berlin by a UFO.

We are shown a collection of stuffed animals and bizarre, occult memorabilia, listen to Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels and are introduced to Krause, the Fuehrer’s valet. With his endless recitation of routine details, Krause suggests that it really is possible to be in the midst of a maelstrom and totally unaware.

* * *

With Our Hitler, director Syberberg completes a cinematic trilogy begun in 1971. His first film, Ludwig - Requiem für einen jungfräulichen König (Requiem for a Virgin King), used many of the same techniques to look at the historical significance of Bavaria's "mad king” Ludwig II.Ludwig ran 140 minutes. In 1976, he made Karl May, a 187-minute biography of the German Zane Grey, a writer of Western romances that were eagerly read by Adolf Hitler.

Overall, Syberberg is more interested in exploring the mythic, cultural and psychological roots of German fascism than he is in the personalities. In 1923, he tells us, Germany was looking for a hero, and Hitler was on hand to answer the people's call.

* * *

Part Three is called The End of a Winter's Tale. Here we meet Himmler and his death's head SS. Here Syberberg confronts "the final solution to the Jewish question.”Looking more like an accountant than a mass murderer, Himmler prattles on about astrology and reincarnation. Like an actor, he is playing a role, one that he claims is dictated by the stars and the forces of history.

Syberberg suggests that the evils of the Third Reich were possible because the evildoers were able to put on costumes, uniforms and regalia to play their parts. They were actors in a larger historical drama that they wanted to believe in and responded to historical impulses that both bore the moral responsibility and provided the impetus.

Hitler makes another appearance, this time as a ventriloquist’s dummy. Directly confronted with a catalogue of his crimes — “you ruined the UFA film organization. It was 20 years before they made decent films again” — he gloatingly adds to the list, describing the “achievements” of his "successors” in the world today.

* * *

This, then, is to be taken as a cautionary tale. The past is significant for what it tells us about the present, the future and ourselves.Germany was a nation that had suffered defeat and humiliation in war, inflation and depression in peace. Despite its pride in its cultural and technological achievements, it felt hemmed in and powerless, as if it were caught in the grip of larger world forces. The world at large was an unfriendly place.

Are there any nations in the world today that fit that description? Hitler, Syberberg reminds us, was democratically elected by the German people, who responded to his promise of a better tomorrow. Hitler is a choice we all make.

* * *

The fourth and final part is called We Children of Hell. It consists of a lecture illustrated by newsreel film footage. Here we are told that Hitler's mission was inspired by the example of the British Empire ("a nation of 52 million runs a fifth of the world") and that he learned the power of a “chosen people" philosophy from the Jews."We must not glorify Hitler,” says a contemporary entrepreneur in the film’s vaudeville-style second half. “But using him for business is permitted.” Welcome to Hitlerland, Bavaria's newest tourist attraction. The chamber of horrors is in the basement.

* * *

Our Hitler is neither difficult nor particularly profound. Its major points could easily be made in a half-hour TV show without sacrificing a single commercial.In terms of technique, it is a filmed stage show. Ken Russell's movies (Mahler, Tommy, Lisztomania) are more inventive and demanding.

Why take all day with it, then? Well, like Werner Erhard and his EST experience, Syberberg doesn't think you can really get “it" unless you work for it.

Fascism, he says, is important. Take a day to think about it. This is film not as entertainment, but as guru.

Coppola agrees. The Vancouver audience is not so sure. Sunday afternoon, the Varsity Theatre was full. About 30 per cent of the starters did not return from the dinner break, though. When the curtains finally closed, at 11:10 p.m., the audience had dwindled to 45 per cent of capacity.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1980. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Are you still here? That’s probably the longest film review that I ever wrote. It was published at a time when a daily newspaper had the space for a critic to take a deep dive into subjects like experimental cinema. Had I been more of an opera buff, I might have made more of the scene in which Syberberg shows us Hitler rising from Richard Wagner’s grave. Worth mentioning in retrospect is that Der Gral was Wagnerian in both its length and visual style. Though there are no formal music credits, excerpts from Wagner’s 15-hour-long Ring Cycle are heard throughout.

Designed as a theatrical motion picture, Syberberg’s opus belongs to an era before binge-watching, the home entertainment phenomenon made possible by the introduction of such technologies as videocassettes (1975), DVDs (1997) and television streaming services (2007). Though long, I was pleased that Our Hitler had something to say. Long-form film fans in the 1960s often struggled with the works of artists like Andy Warhol. His movies went on forever — 1964’s Sleep watched John Giorno do just that for more than five hours; 1965’s Empire stared at the iconic New York building for about eight hours — to no apparent purpose.

Considerably more ambitious was Soviet director Sergei Bondarchuk’s seven-hour adaptation of War and Peace. I remember spending an afternoon and evening in New York City’s DeMille Theatre watching the two-part six-hour version released in North America in 1968. In 1973, seeing the 332-minute restoration of Abel Gance’s 1927 Napoléon in San Francisco was a major movie event. (The silent epic was trimmed to 235 minutes for its 1982 Vancouver release.)

The shift in the entertainment experience was already well along when Christine Edzard’s 357-minute adaptation of Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit played locally in 1989. The phrase “film franchise” was entering the language to describe the series productions that are now fodder for the occasional theatrical movie marathon, and the binge-watching that’s seen so many though the COVID-19 pandemic.