Saturday, May 22, 1976.

THE MISSOURI BREAKS. Written by Thomas McGuane. Music by John Williams. Directed by Arthur Penn. Running time: 126 minutes. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: violence and coarse language.

"YOU'RE BEGINNING TO RAVE," rancher David Braxton (John McLiam) angrily tells hired gunman Robert E. Lee Clayton (Marlon Brando). "And you're beginning to bore me."

Braxton has had about enough of Clayton's maddening mannerisms. And, truth to tell, Marlon Brando is a bore. Let's forget him for a few minutes, and try to sort out just why The Missouri Breaks is such a godawful mess.

At first glance the project has all the ingredients for a classic western drama. The plot is archetypal. A Montana land baron, concerned about losses from his herds, hires a professional "regulator" to eliminate the rustlers.

Unbeknownst to Braxton, his pretty young daughter Jane (Kathleen Lloyd) is in love with Tom Logan (Jack Nicholson), one of the malefactors.

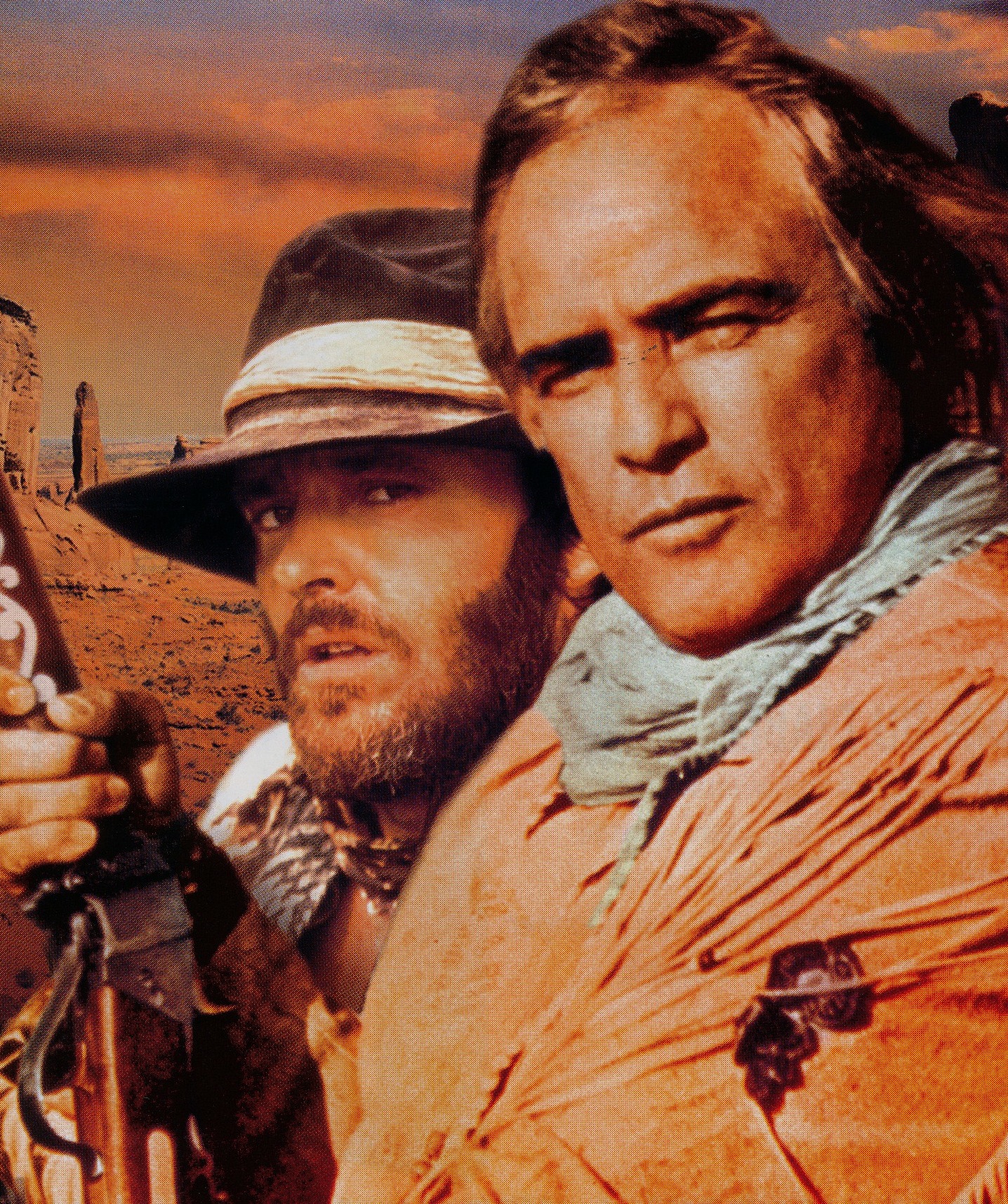

The cast should be money in the bank. Nicholson, the 1975 Oscar winner (for One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest), plays the rustler. Brando, of course, is the regulator.

Director Arthur Penn, with 1967's Bonnie and Clyde to his credit, has an enviable track record. At one time or another he has worked with virtually every top star in Hollywood, a collection that includes Paul Newman (in 1958's The Left Handed Gun), Robert Redford and Brando (The Chase; 1966), Dustin Hoffman (Little Big Man, 1970) and Gene Hackman (Night Moves, 1975).

With United Artists putting up front money for a prestige project, what could possibly go wrong?

The script, that's what. Poor old Penn has gotten badly out of touch these last few years. He accepted a script from novelist and novice director Thomas McGuane. Right at that moment he should have heard the warning bells ringing.

McGuane was responsible for two of 1975's worst movies: Rancho Deluxe and 92 in the Shade. The films were alike in their total lack of narrative drive, their preoccupation with innocent-looking (but sexually predatory) females, and the presence of unhinged patriarchs.

McGuane made his own disastrous debut as a director with 92 in the Shade, a film that gave us Peter Fonda and Warren Oates exchanging sweaty non-sequiturs in one of the most enervating clashes of non-wills ever filmed.

Rancho Deluxe, directed by Frank Perry and set in the contemporary West, paired Jeff Bridges and Sam Waterston. It was practically a modern-dress run through for The Missouri Breaks.

McGuane has been finding a lot of work lately, so someone must like his stuff. To give him his due, he has a bizarre sense of humour that occasionally sets up a good one-liner. A storyteller, he ain't.

And the Western, as any Louis L'Amour fan knows, is a storyteller's medium. To date, director Penn has been more interested in meaning and mood than storylines. He needs a solid script to keep him on track. Lacking one, he makes a Missouri Breaks.

The new film suggests that Penn hasn't seen a Western since the last time he made one. He is out of touch with what's been going on, with the result that Missouri Breaks recaps the entire dirt Western trend of the past five years.

Throughout, there are visual and thematic echoes of other recent movies, among them Robert Altman's McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971), Robert Benton's Bad Company (1972), Stan Dragoti's Dirty Little Billy (1972), James Frawley's Kid Blue (1973) and even Penn's own Little Big Man.

Each, at the time of its release, had a freshness of outlook and points to make. By comparison, Missouri Breaks has little that's new in its outlook, and no point at all.

So what about all that high-priced help?

Nicholson, his character's virtue laid siege to by newcomer Lloyd (a pretty lady miscast in a role that calls for the wanton self-awareness of a Lee Purcell), is a listless imitation of Dennis Hopper's inept outlaw, Kid Blue. His befuddlement, however, fits in well with the cheap-shot humour in McGuane's script.

Brando, on the other hand, plays a squirrel. As Lee Clayton, he goes on his murderous rampage affecting as many changes of costume and accent as there are players in the cast. New York Times film critic Vincent Canby observed that "he mugs in a soft, genteel way, using odd pauses and glances off-screen, that force our attention to him with no relation to the meaning of the scene."

Glances off-screen, eh? In a recent interview, the lovely Miss Lloyd blows Brando's cover. America's "finest actor" has grown too big to trouble himself with learning lines.

He uses cue cards.

Mumbles Marlon isn't acting, he's reading!

Arthur Penn used to be an innovator. His pictures have been trend-setters. Even his underrated Night Moves turned out to be one of 1975's best films.

Unfortunately, with The Missouri Breaks, he's more interested in exploitation. Artistically, it's in the same class as the current Grizzly, schlock director William Girdler's Jaws clone that features "18 feet of towering fury" and not one inch of originality.

* * *

CUT AND RUN — This week The Missouri Breaks opened in 900 theatres in the U.S. and Canada. This, according to United Artists senior vice-president James R. Velde, "was the biggest simultaneous opening scheduled" in that company's history.When movies open in that many places all at once, one suspects that something is wrong. Maybe the producers are hoping to break big, take the money and run before bad reviews and word-of-mouth from filmgoers have a chance to take their toll on the box office.

Sometimes such suspicions are unfounded. Sometimes, as in the case of an all-out disaster like The Missouri Breaks, they make a lot of sense.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1976. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Early in the film, the Logan gang crosses the border into Canada. They steal horses from the local Northwest Mounted Police detachment, while the upright peace officers are attending chapel services. The incident, like much of the film's action, seems off the wall. I find myself wondering if the whole thing wasn't a private joke between screenwriter Thomas McGuane and his then-wife, Canadian actress Margot Kidder (who he met during the making of his 1975 feature 92 in the Shade). As noted above, The Missouri Breaks was among the first features to adopt the screen saturation-release strategy pioneered nine months earlier by Jaws. In fairly short order, the relative success of the approach led to movies routinely being released in more than 1,000 theatres simultaneously.