Monday, May 5, 1975

MANDINGO. Written by Norman Wexler. Based on the 1957 novel by Kyle Onstott. Music by Maurice Jarre, Hi Tide Harris and Muddy Waters. Directed by Richard Fleischer. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: sex and brutality.

THERE IS A REAL temptation to call Mandingo an accident, to say that the feeling of parody is unintentional, and to suggest that the actors really didn’t know that they were playing it for laughs. It’s a temptation that should be resisted.

Director Richard Fleischer has been in the business too long — 29 years [as of 1975] — and made too many movies — 36 — not to know satire when it bites him. With Mel Brooks successfully doing it to the Western (Blazing Saddles) and the horror film (Young Frankenstein), Fleischer probably decided that it was time to do a take-out on The Big Bold Novel.

When you think about it, there really was no other way. Mandingo, the novel — a stage version was tried some 14 years ago [1961] — is trash.

Published in 1957, it was the first work of fiction for Kyle Onstott, only identified to readers as “the author of many semi-technical and technical works.” I remember a friend in high school offering me a copy.

“Never mind The Carpetbaggers,” he said conspiratorially. “Read this.” I took it, but I couldn’t really get into it. After a few pages of hearing its hero boast how “when I whups, I whups! Takes the meat right off your bones,” (to which the slave so addressed replies, “Nah, suh, please suh, Massa suh, I be spry. I ain’t gwine sloth no mo’.”), I just gave up on it.

Onstott didn't. Mandingo sold five million copies and its author found time to grind out several sequels. All, apparently, are set in the ante-bellum South somewhere in the neighbourhood of Falconhurst, described on the cover of the most recent paperback edition as a "human breeding farm."

Now, that sounds terrible. It would look pretty bad on screen as well, except for one thing. Four years ago the American film industry discovered that there was a big black audience. Since then the various adventures of Shaft, Slaughter, Super Fly, Cleopatra Jones, Black Belt Jones and Nigger Charlie have taught us that ain't nobody gwine — er, that is to say, there isn't anybody who hasn't felt the effects of the new black presence in the movies.

Today [1975], a movie like Mandingo has a lot in common with The Ten Commandments in that it shows us Southern American slavery with the kind of big screen overstatement that De Mille used to describe the plight of the Jews in ancient Egypt. And it’s every bit as funny.

James Mason, a veteran English actor, plays Warren Maxwell, the patriarch of Falconhurst, with considerable gusto. His major problem is his son and heir, Hammond (Perry King, last seen in The Lords of Flatbush), a shy young man who should be looking for a wife.

Although he knows his way around the plantation's "wenches," — "Master's duty to pleasure the wenches first time,” papa tells him, explaining their Southern droit de seigneur — young Ham is self-conscious about his game leg. Nonetheless he accepts a match with his "kissin' cousin," Blanche (Susan George, an English actress who looks about as 19th century as Canada’s Anik satellite).

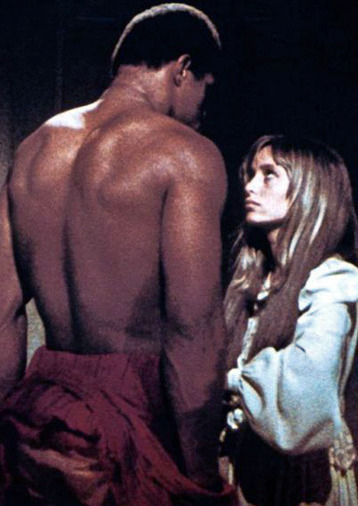

For various indelicate reasons, Ham decides that he prefers his regular "bed wench," Ellen (Brenda Sykes), to his wife. Blanche, in turn, complicates matters by going to Mede (Ken Norton), a regal Mandingo slave, to demand solace.

Mandingo was written to entertain closet racists, and titillate those fascinated by the idea of miscegenation. But didn't the movies grow past that stage the day that Raquel Welch went into a clinch with Jim Brown (in 1968's 100 Rifles)?

As a result, Fleischer plays it for the inherent comedy. Pulp situations are grotesquely inflated, and Norman Wexler's script bristles with barbed assaults on the filmgoer's disbelief.

In one exchange, for example, Blanche takes exception to Ham’s charge that she was less than pure on their wedding night. "I was too a virgin," she whines,

"You was oncet,” he says, discounting her claim, "but not last night."

Oncet upon a time, Mandingo might have caused outrage. Not anymore. Poor taste aside, it's a movie for the people who saw the fun in director Russ Meyer’s Beyond the Valley of the Dolls. It's just bad enough to be good.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1975. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: “Bad enough to be good”? Forty-six years later, I’m taken aback by my glib acceptance of a truly awful movie. My contemporary (and fellow Russ Meyer fan) Roger Ebert came closer to the truth, writing that “Mandingo is racist trash, obscene in its manipulation of human beings and feelings, and excruciating to sit through. . .” He was based in Chicago, where the population was about 30 percent black, and had a more immediate appreciation for the film’s context. Ebert displayed more empathy for the feelings of his fellow Americans than I did.

By contrast, I live in Vancouver, where our visible minorities are Asian: Chinese, Japanese, East Indian, Filipino and Korean. It’s taken me a lifetime to recognize that, like most Canadians, I view the world through the prism of white privilege. We live in a world where we are all racialists because racism is baked into the system. Once we acknowledge that — dare I use the expression “call a spade a spade”? — we can take on the task of trying to be responsible human beings. That said, the above review should be viewed in the context of its specific time and place.

Mandingo arrived in town at the high point of the black exploitation (blaxploitation) movie era. It was among more than a dozen pictures released in 1975, pictures that included comedies (Black Shampoo), westerns (Boss Nigger), horror (Dr. Black, Mr. Hyde) and a cartoon feature (Coonskin). Drum, the sequel to Mandingo, found its way into theatres a year later. The positive spin on this trend was that Hollywood had discovered the economic power of the black audience, and its visibility would someday result in the ultimate realization of Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream of racial equality. A year earlier (1974), we'd seen the outrageously hilarious Blazing Saddles and Young Frankenstein, movies that gloried in challenging the boundaries of the acceptable. At a distance, it was possible for me to see the problematic Mandingo as satire, albeit one in seriously bad taste. The world we live in today suggests that I had rather too much faith in the power of popular culture to bring about positive change.

Kyle Onstott never saw what the movies would make of his psycho-sexual fever dreams. In June, 1966, shortly after the publication of the fourth Falconhurst novel, the lifelong bachelor died at the age of 79.