Friday, April 8, 1994.

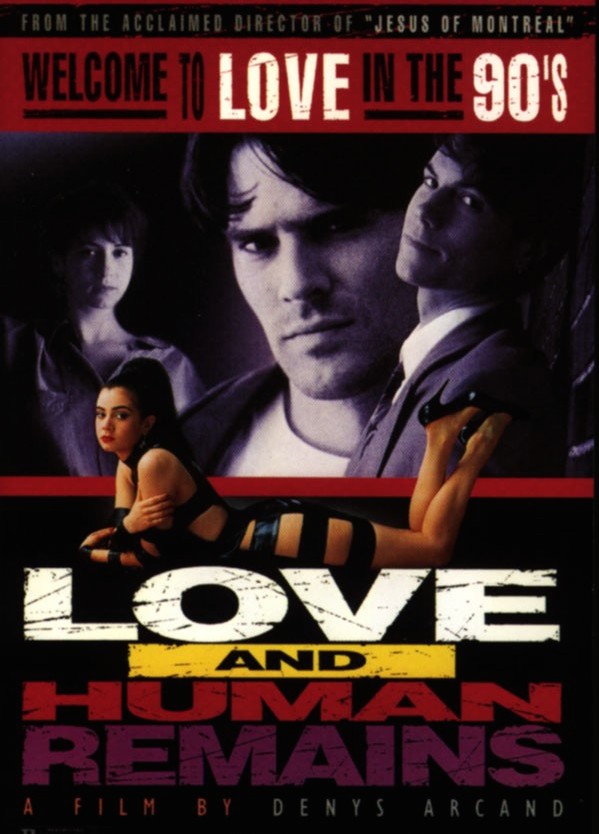

LOVE AND HUMAN REMAINS. Written by Brad Fraser, based on his 1989 stage play Unidentified Human Remains and the True Nature of Love. Music by John McCarthy. Directed by Denys Arcand. Running time: 99 minutes. Rated 14 Years Limited Admission with the B.C. Classifier’s warning "some violence and nudity, suggestive scenes, very coarse language.”

WHAT'S IN A NAME?

If Denys Arcand's subversively serious new relationships comedy had been made in the slick 1970s, its name would have reflected that sensation-weary era's smirking salaciousness. They'd have called it Who Is Killing the Single Women of Ottawa?

In the shocking 1960s, they'd have gone for the gut with something direct and unambiguous: Sex and the Serial Killer.

Based on Brad Fraser's 1989 stage play, Unidentified Human Remains and the True Nature of Love, Arcand's compelling Canadian picture focuses on the generation that came of age in the dead-end 1980s. His film version is called Love and Human Remains, a title in keeping with the dazed-and-confused bite of 1990s reality.

On offer is the story of six characters in search of love or, at least, some form of meaningful connection. Complicating matters is David McMillan's observation that "I never met anyone born after 1965 who wasn't incomplete somehow."

"Why's that?" asks David's roommate, Candy Nesbit (Ruth Marshall).

"Microwave ovens, I think."

A friend rather than a lover, David (Thomas Gibson) shares his feelings and household expenses with Candy. A former television child star, David is gay.

He appears to be at ease with his life as a waiter in a classy Ottawa restaurant.

Candy, by contrast, is anxious about her lack of a loving relationship. Or at least her need for "someone who'll hang around for my orgasm."

Anxiety turns to nervousness when two different people come on to her. One is Robert (Rick Roberts), a hunky bartender who's a bit too enthusiastic about getting her into bed.

The other is Jerri (Joanne Vannicola), a sweet-faced elementary school teacher eager to instruct Candy in same-sex ed. David, meanwhile, is being courted by his co-worker, Kane (Matthew Ferguson), a 17-year-old busboy exploring his attraction to older men.

David is also close to Benita (Mia Kirshner), a clairvoyant call girl who specializes in bondage and domination fantasies. His best buddy is Bernie (Cameron Bancroft), an apparently bisexual civil servant.

As if that weren't enough plot for one movie, there are strong hints that one of our principals is a homicidal maniac responsible for the deaths of several Ottawa-area women.

In his first English-language feature, Arcand again demonstrates his world-class directorial touch. With two previous foreign-language picture Academy Award nominations — for The Decline of the American Empire (1986) and Jesus of Montreal — to his credit, he knows that serious cinema buffs are paying attention.

And so they should. A past master at layering literate entertainment upon sharp social commentary, Arcand uses his finely-tuned Québécois sense of the absurd to reflect on the dilemma of young adulthood in not-so-big cities.

"You ever feel like you're nothing like everyone else in the world?" sexually confused Candy asks her "professional faggot" David.

"Only all the time," he says.

Their mutual confusion notwithstanding, theirs is a world full of dangers and unexpected magic, possibilities and unwanted unpleasantness, from which they can't hide.

Like Holland's Paul (Basic Instinct) Verhoeven, Arcand sees the world as it is. His talent is for shaping immediate reality into penetrating parables that give now a name.

Today, it is a story called Love and Human Remains.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1994. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Grown men wiped tears from their eyes as the cast of Kill Me Now took their bows Tuesday night (October 16) at Vancouver’s Firehall Arts Centre. Under the direction of Touchstone Theatre’s Roy Surette, playwright Brad Fraser’s tale of love, life and disability gets its West Coast premiere in a production that is both darkly comedic and intensely human.

In outline form, it sounds grim. Widower Jake (Bob Frazer) is the primary caregiver for his physically disabled son Joey (Adam Grant Warren), a teenager suddenly confronting the reality of sexual desire. A college instructor, Jake is involved in a long-term affair with Robyn (Corina Akeson), a former student who is married with children of her own. Jake gets some help from his spinster sister Twyla (Luisa Jojic) and Joey’s friend from his special-needs school, mentally-challenged Rowdy (Braiden Houle). Then everything changes for everyone when Jake suffers a sudden, severe disability of his own.

In performance, it’s a compelling, positively energizing encounter with reality. Credit a uniformly fine cast, five splendid performers who all breathe life into their individual roles. Together, they make it clear that although nobody’s perfect and life’s not fair, adults deal with it. And yes, I’ll admit that the truth of it had me in tears, too.

* * *

Denys Arcand’s 1993 feature Love and Human Remains introduced movie audiences to the work of Brad Fraser. Critics, ever given to labels, were already used to calling the Edmonton-born playwright “the bad boy of Canadian Theatre.” His profile in The Canadian Encyclopedia tells us that he was “physically and sexually abused as a child [and] troubled as a teenager,” but that “at 16 he saw a play at Edmonton's Victoria Composite High School and was immediately drawn to theatre.” The next year he wrote his first play.According to Fraser’s Wikipedia entry, “his plays typically feature a harsh yet comical view of contemporary life in Canada, including frank depictions of sexuality, drug use and violence.” A 1991 New York stage production (and Arcand’s film adaptation) of his Unidentified Human Remains and the True Nature of Love earned him international prominence. In 2002, Fraser made his own feature directorial debut with Leaving Metropolis, adapting his 1994 play Poor Superman to the screen. Set in Winnipeg, it told the story of a gay artist in a complicated relationship with a straight restaurateur.

An advocate for gay rights, Fraser was the host of Jawbreaker, a cable-TV talk show that ran for 27 episodes in 2002 on the specialty channel PrideVision (now known as OUTtv). He also wrote eight episodes of Queer as Folk, a shot-in-Toronto TV series that he also worked on as a co-producer and executive story editor. Now 59, Brad Fraser no longer qualifies as a “bad boy.” But, as the current production of his Kill Me Now demonstrates, the man still has his edge.