Friday, April 27, 1990.

Q & A. Based on the 1977 novel by Edwin Torres. Music by Rubén Blades. Written and directed by Sidney Lumet. Running time: 132 minutes. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: frequent very coarse language, some violence.

TWENTY YEARS AGO [1970], POLICE corruption was a shock. That it was more than an individual aberration, that it had become institutionalized — that idea was both terrible and new.

It shocked us in 1973's Serpico, director Sidney Lumet's street-level morality play about an honest cop who blows the whistle on his bent brothers in blue.

Today it's a given, the stuff of exploitation rather than exposé movies. Even Lumet accepts it. His gritty, challenging new film Q & A opens with a man being shot outside the door of a backstreet after-hours club.

Instead of fleeing, the killer steps forward and forces a gun into the corpse's hand. Corralling some "witnesses" from the club, he flashes his police badge and insists they take note of the dead man's weapon.

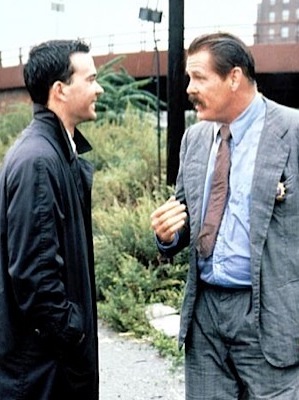

Later the same night, assistant district attorney Al Reilly (Timothy Hutton) is impressed. Called in to conduct the official "Q. & A." session, he listens with admiration as homicide Lt. Michael Brennan (Nick Nolte) recalls the incident for the record.

A cop's cop, Brennan gives a statement that "covers everything," leaving the young lawyer with no further questions. Going in, Reilly's boss, D.A. Kevin Quinn (Patrick O'Neal), told him the incident was "justifiable homicide," a case that's "cut and dried."

We know that it's not.

Collecting facts for presentation to a grand jury, the squeaky clean Reilly soon begins to suspect as much.

I'm impressed. Director Lumet, once cited for his "strained seriousness" by cinema historian Andrew Sarris, gets better with age.

A liberal with directorial roots in television's golden age, Lumet is always more comfortable on New York's streets than a Hollywood back lot. The films that earned him his Oscar nominations — Twelve Angry Men (1957), Dog Day Afternoon (1975), Network (1976), The Verdict (1982) — show the direction his conscience has given his career.

Though he's been both in and out of style, he's never lost it. An intense, immediate study of conflicting loyalties, his Q & A is as dark and compelling as Coppola's The Godfather.

Adapted by Lumet from Edwin Torres’s 1977 novel, it takes up the issues of family and tribe that were at the heart of his most recent films (1988’s Running on Empty and 1989’s Family Business). Reilly’s investigation explores the gulf between what’s legal and what’s right.

If Serpico shocked us with its look at a corrupt system, Q & A exposes something every bit as nasty: corrosive racism.

From squad room humour to “justifiable homicide,” everything is tinged with a poisonous hostility based on the perceived differences between Jew and gentile, black and white, Hispanic and Anglo-Saxon.

''It's all coming apart, Al,'' Brennan tells Reilly, one Irishman to another. ''I want it to be the way it used to be.’’

It can't be, of course. As he digs into the complex web of relationships that link lawmen with outlaws, Reilly discovers that even he is not the man he would be.

Nolte's overweight, empty-eyed portrait of a cop gone bad is as memorable as Orson Welles’s seedy Hank Quinlan in the classic Touch of Evil (1958). A tragic figure, he is the lost soul of this urban epic.

Fine, rather than fun, Q & A asks all the right questions.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1990. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Lt. Brennan’s wishes notwithstanding, it never can be the way it was. Real-life bad cop Derek Chauvin is behind bars because of a complex web of insights and innovations that occurred in the years following the 1990 release of Q & A, innovations that link two women in a tale of tech. It all began with a birth announcement.

On June 11, 1997, proud papa Philippe Kahn wanted to tell all his friends about the arrival of his daughter Sophie into the world. Not just any dad, the Paris-born Kahn was an engineer/entrepreneur, and he'd been working on adding a camera to his mobile phone. Wikipedia tells us that, while his wife was in labour in a Santa Cruz, Calif. hospital, “Kahn jury-rigged a connection between a mobile phone and a digital camera and sent off photos in real time to the picture messaging infrastructure he had running in his home.”

Jump ahead to 2004, a time when every smartphone can take pictures. On February 4, Internet entrepreneur Mark Zuckerberg launched Facebook into cyberspace, and with it the modern era of social media. (YouTube followed a year later, on February 14, 2005.)

Born March 23, 2003, Darnella Frazier never knew a time without the cameraphone. The Minneapolis teen had one on May 25, 2020, the day she recorded the death of George Floyd under Chauvin’s knee. Posted to the Internet, it was evidence of a murder. What would have been passed off a “justifiable homicide” in the time of Q & A went to trial. Between them, Ms Kahn and Ms Frazier changed the world (a fact recognized by the Pulitzer Prize board, who awarded a special citation to Frazier in 2021).

See also: Today’s five-feature Law Enforcement Appreciation package includes director Abel Ferrera’s 1992 tale of guilt Bad Lieutenant; David Zucker’s 1991 farce The Naked Gun 2½: The Smell of Fear; Peter Segal’s 1994 comedy Naked Gun 33⅓: The Final Insult; Sidney Lumet’s 1990 crime drama Q & A; and Jonathan Kaplan’s 1992 suspense thriller Unlawful Entry.