Friday, January 20, 1988.

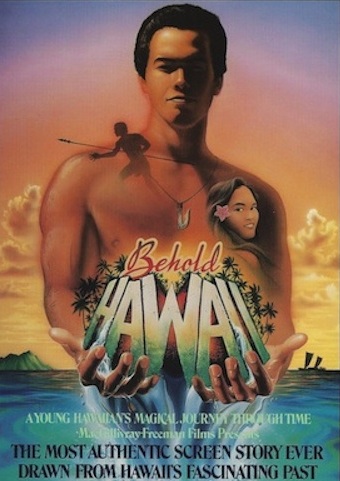

BEHOLD HAWAII. Written by Alec Lorimore. Music by Basil Poledouris. Produced and directed by Greg MacGillivray. Running time: 39 minutes. General entertainment.

THE GIANT IS STIRRING. Behold Hawaii, says producer-director Greg MacGillivray, "takes IMAX/OMNIMAX to a new plateau."

The ultimate medium for nature documentaries and travelogues, the mega-frame film process has been used, finally, to tell a story with dialogue, plot and fictional characters. “I’ve shown that it’s possible to shoot (an IMAX) feature."

MacGillivray is both right and wrong. His 39-minute tale of Keolo (Blaine Kia), a modern Hawaiian youth who experiences a dramatic visit to the world of his Polynesian forefathers, is an IMAX first.

On the other hand, we’ve known that the big screen could tell stories since 1962's The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm, then How the West Was Won (1963), the sixth and last true Cinerama release. Though the $15-million production couldn't save this doomed giant screen process, it was a success in its own right.

Cinerama existed for about 10 years. At the height or its popularity (1957), there were fewer than 30 theatres worldwide equipped to show it.

Introduced in 1970, the technically superior IMAX has lasted just about twice as long. Today [1988], nearly 60 locations are equipped to show its library of more than 50 films.

Behold Hawaii, MacGillivray's lush proto-feature, again demonstrates the big frame's power to deliver images of breathtaking beauty. Unfortunately, it also magnifies the deficiencies in its lacklustre screenplay and less-than-epic acting.

Screenwriter Alec Lorimore sets his story during the the annual Makahiki festival, the celebration of the ancient Hawaiian New Year. Although scheduled to perform the hula during the ceremonies, Keola doesn’t fully appreciate the cultural significance of a dance form that has been reduced to Tiki kitsch in American popular culture.

The young man’s consciousness is raised during a night filled with dreams of “the old ways.” In a series of docudrama vignettes, he experiences island life as his people once lived it, and continue to express in their dance.

He learns the fundamentals of fishing, participates in some colourful ceremonies and fights for the affections of Maile (Kanani Velasco), the beautiful wahine princess. The next day, his hula reflects Keola’s new energy and understanding.

To producer-director MacGillivray’s credit, Behold Hawaii is an honest attempt to go beyond the tourist-brochure clichés and show us a more nuanced view of Polynesian society. An ambitious effort, it still relies on pictures rather than performances to carry the day.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1983. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Blaine Kia, who made his film debut in Behold Hawaii, went on to make the preservation and promotion of Hawaiian customs his life’s work. In addition to acting as a Honolulu-based cultural consultant, he travels the Pacific Rim in his role as Kuma Hula — teaching master — for 17 independent hula institutions. His circuit includes the Kauhane School of Polynesian Dance located in Vancouver’s Maple Ridge suburb. A musician as well as a dancer, Kia performs Hawaiian “roots music” with his colleague Kalei Kahalewai. In late July (2017), they released a CD titled Huaka’i Ku’u Poli.

With some 35 IMAX theatrical shorts to his credit, Greg MacGillivray is among the most prolific of the independent filmmakers producing original material in the big screen process. His first was the 27-minute documentary To Fly!, made in 1976 for the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum. MacGillivray's projects have taken him to the edge of space and to the ocean depths, journey’s that have earned him two documentary short subject Oscar nominations (for 1995’s The Living Sea and 2000’s Dolphins). In mid-July, MacGillivray attended the premiere of his 2017 documentary We, The Marines, a 40-minute celebration of life in the U.S. Marine Corps made for the opening of the Medal of Honor Theatre in Triangle, Virginia’s National Museum of the Marine Corps.

See also: For more on Canada’s big screen innovations, IMAX and OMNIMAX, see my Reeling Back postings on IMAX/OMNIMAX at Expo 86 (1986). Among the IMAX film reviews to be found in this archive are Transitions (1986), Fires of Kuwait (1992) and Titanica (1993).