Friday, May 5, 1972

SILENT RUNNING. Written by Deric Washburn, Michael Cimino and Steven Bochco. Music by Peter Schickele. Lyrics for Joan Baez's songs by Diane Lambert. Directed by Douglas Trumbull. Running time: 89 minutes. General entertainment.

They took all the trees, put 'em in a tree museum;

And they charged all the people a dollar and a half just to see 'em.

Don't it always seem to go,

That you don't know what you've got till it's gone?

They paved paradise, and put up a parking lot.

And they charged all the people a dollar and a half just to see 'em.

Don't it always seem to go,

That you don't know what you've got till it's gone?

They paved paradise, and put up a parking lot.

— Big Yellow Taxi (1970)

DIRECTOR DOUGLAS TRUMBULL has gone Joni Mitchell one worse. In his film Silent Running, he postulates a world that no longer has room even for the tree museums.

Instead, representative samples of Earth's greenery have been shot into space with orders to maintain a holding pattern until the day when reforestation of the planet becomes practical.

The venture, apparently, is a commercial one — a goodwill gesture on the part of the corporations that have made terrestrial life for the plants impossible. Skeleton crews, assisted by ambulatory robot drones, maintain the space-borne arks and tend the forests, each one contained in its own climate-controlled geodesic dome, ironically reminiscent of Vancouver's Bloedel Conservatory on Little Mountain.

Ecological disaster has replaced thermonuclear war as North America's No. 1 nightmare, and Trumbull, one of Stanley Kubrick's key crewman in the creation of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), has created his own strikingly visual parable of man's last stand.

The result is not so much science fiction as science fantasy. His film's screenplay is more Lewis Carroll than Arthur Clarke.

Earth, where man was once part of nature, has become a well-ordered machine.

Nature has become part of the machinery, relegated to orbital space where it, too, must depend on artificial systems and mechanical order.

Then, after eight years in the holding pattern, the order is given to abort the project, destroy the forests and return the expensive mechanical museums to commercial use.

Three of the four crewmen on the space station Valley Forge are elated.

One isn't.

During the long assignment, Freeman Lowell (Bruce Dern, the twitchy villain who gunned down John Wayne in 1972's The Cowboys) has become an eco-freak. Literally.

Wandering about in hooded robes, he rattles his shaggy locks in a righteous frenzy every time his crewmates sit down to a meal of synthetic food. The order to abort the mission really drives him crackers.

His shock — and the audience's — is compounded by the sight of his crewmates. Bright faced, their mouths full of bland NASA-chatter, they arm their atomic bombs and gleefully set out to destroy the final forests, mankind's ultimate hollow triumph over nature.

Lowell's madness is murderous. He destroys the hollow men to preserve the last forest, and flees with it deeper into space.

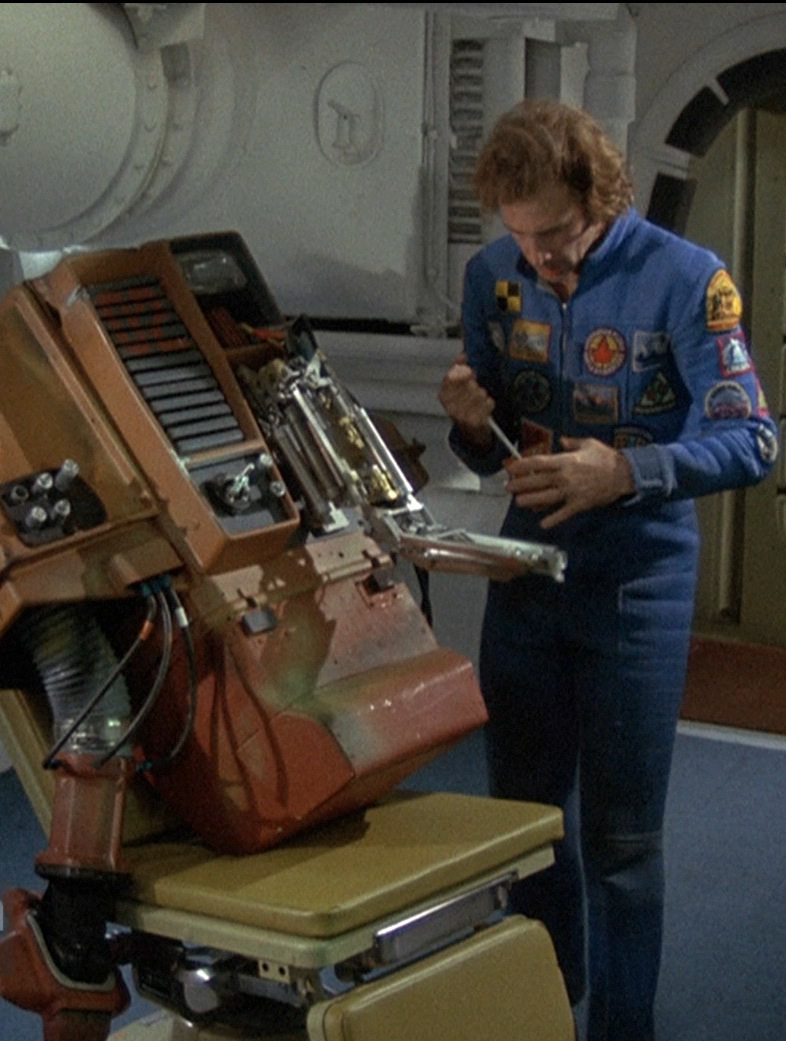

His only companions are his drone servants (hard-shelled costumes for the performers — legless amputees — who operate them from within). In honour of their engaging, duck-like gait, he names them Huey, Dewey and Louie (after Donald Duck's comic-book nephews), and re-programs them to help him in the forest.

The drones are cute, perhaps too cute. Lowell is mad, perhaps too mad.

The film, however, is effective both on the superficial level of special effects, and on the deeper level of telling a story beneath its story.

Even more than its visual predecessor 2001, Silent Running serves to prompt some profound thinking.

Lowell, with his yellowing Smokey the Bear poster, is the last man to shoulder the responsibility given man by the God of Genesis. On the the Sixth Day, God gave man, His creature, dominion over His creation, along with the responsibility to use it wisely.

In the end, the last man turns over final responsibility to his creature — "Take good care of the forest, Dewey" — the mechanical Junior Woodchuck, who will care for it until, somewhere in space, a wiser race finds it.

Too deep?

Perhaps.

But Silent Running is the sort of film that will prompt many reactions, depending upon its audience. It is a special effects show, an eco-poem and a complex, inverted metaphor.

Its flaws never overcome its fascination.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1972. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Climate crisis? We can't say we weren't warned. From Cornel Wilde's No Blade of Grass (1970) to Roland Emmerich's The Day After Tomorrow (2004), filmmakers have been sounding the alarm regarding environmental collapse. Douglas Trumbull's Silent Running remains among the best of such fictional considerations of the consequences. At the time of its release, though, the critical reaction was less focused on its message than its high-tech look and loveable "drones," the precursors to the "droids" we would meet later in Star Wars. Naming them Huey, Dewey and Louie was a screenwriter's nod to the Disney ducks, first seen in a 1937 newspaper comic strip, but best known from their appearances in the comic books written and drawn by Carl Barks. They also served as a reminder of the important role that Walt Disney (the man, not the media corporation that came into being after his death in 1966) played in shaping the eco-consciousness of a generation. When his Disneyland television series first went to air in 1954, it introduced viewers to a "Magic Kingdom" consisting of four "lands." Among them was Adventureland, created to highlight the series of True-Life Adventure documentary shorts and features that his studio had been making since 1948. I like to think that Trumbull (who was born in 1942) grew up with the work of "stealth conservationist" Disney, and that Trumbull's directorial debut feature reflects the convergence of his own encounters with Adventureland and Tomorrowland.