Monday, June 27, 1977

STAR WARS. Music by John Williams. Written and directed by George Lucas. Running time: 121 minutes. General entertainment.

IT WAS, LOOKING BACK on it, a midsummer night's delight.

Still, I couldn't help feeling a bit edgy going in.

Time had already proclaimed it the year's best movie. Newsweek loved it, and refused to think about the kind of people who wouldn't share those feelings.

The operative word was ''fun." It's been used so often in the last month that it has taken on the tone of a pronouncement rather than a promise. You vill haff fun . . . !

Relax. Star Wars is . . . well . . . fun. The film on the screen is nowhere near as daunting as all those intensely analytical articles, the ones that insist on explaining directorial influences with such archaeologic gravity.

Writer/director George Lucas is not like that at all. He's more like . . . well . . . one of us. Did you know that he's part owner of a little bookshop in New York that specializes in fantasy art and comic books?

Star Wars, with its breakneck pace and unbelievable special effects, brings the visual world of comics to the screen. If, by contrast, Lucas's script seems simple-minded, just remember that in the comics, the content of the word balloons is less important than the quality of the graphics.

In critical terms, the movies have always occupied a middle ground, somewhere between such garishly obvious comic art and the stark mindscapes of the printed page. Indeed, filmmakers are constantly rediscovering how it is impossible to turn a great book into a great movie.

(Pulp fiction, on the other hand, often inspires unexpectedly fine films. Trash novels such as Jaws and The Godfather have become movie classics.)

Lucas, with his unblushing comic-book bias, has created a classic of another order entirely. In Star Wars, he takes filmgoers into that visceral, visual world where the characters, causes, settings and emotions are all larger than life, the direct extension not of experience, but of imagination.

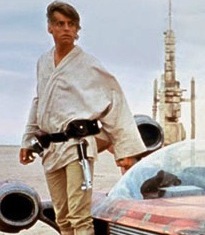

Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) is every boy who ever imagined himself the son of a hero, and the heir to adventure. Princess Leia (Carrie Fisher) is every girl who ever wanted to share the excitement and the danger, and yet still be a beautiful, high-born lady.

Set in a future that is "a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away, " Star Wars is an irresistible dream.

Lucas, of course, is noted for bringing our deepest fantasy-memories to life.

His first film, THX 1138 (1971), expressed the adolescent's craving for individuality in an increasingly conformist world. The incredible American Graffiti (1973) was both lighthearted and unsparing as it relived the bittersweet end of adolescence.

Star Wars is simpler, more direct fare. It is life as every 13-year-old would have it be. It is not so much nostalgic for a particular series of films or books as it is a total re-immersion in the purest of childhood dream worlds.

In this, Star Wars is a welcome, wonderful vision. Even at 13, the chiId may sense that the adult world will be as difficult and as stifling as the evil galactic empire, but he still looks on life as a glorious adventure. Star Wars captures that moment, and lets us live in it once again.

Sunday, Aug. 26, 1979

IF AUDIENCE ENJOYMENT CAN be measured in dollars, Star Wars is the biggest crowd pleaser of all time. Since its premiere on Tuesday, May 22, 1977, the super space fantasy has earned more than $164,765,000 in rentals in the U.S. and Canada alone.The picture is back with us for a brief re-release. The crowds are back, too, much to the delight of Canada's Odeon Theatres.

This, then, is the ideal time to pass on some Star Wars stories, a selection of items that I don't think you'll have heard before. To begin, let me tell you about the parts that were left out of the finished film, and the Canadian actor who was lost with them . . .

* * *

POOR GARRICK HAGON. In 1976, the Toronto-born actor was cast in the role of Biggs Darklighter, a native of Tatooine and Luke Skywalker's best friend.Though primarily a stage actor, Hagon had managed a few screen credits, among them bit parts in Antony and Cleopatra (1972) and Mohammad, Messenger of God (1976). Under the direction of George Lucas, he played all of his Star Wars scenes opposite Mark Hamill.

The film, as originally shot, has Luke (Hamill) looking up into the sky and seeing the battle between Darth Vader's imperial cruiser and Princess Leia's rebel spaceship. Leaping into his landspeeder, Luke rushes to the settlement of Anchorhead, where he meets his old friend Biggs.

Unlike Luke, Biggs has managed to get off Tatooine to attend the space academy. He is now serving as first mate on the frigate Rand Ecliptic.

Like Luke, Biggs is sympathetic to the rebel alliance. He confides to Luke that he's planning to jump ship and join the rebels the first chance he gets.

They will meet again near the end of the film, at the rebel base on Yavin's fouth moon. Luke is to fly in the attack on the Death Star. As he is about to climb into his fighter, he is spotted by Biggs, and they discover that they are wingmen.

We never saw any of this. All of these scenes ended up on the cutting-room floor. In the finished film, we hear Luke say things like "Biggs is right! I'll never get out of here" (while cleaning his Uncle Owen's newly purchased robots, C-3PO and R2-D2), and "that's what you said last year, when Biggs left'' (to his Uncle Owen over dinner).

We don't actually see Biggs until after the attack fighters have been launched. Moustachioed, he is identified as Red Three. He's the last rebel shot down by Darth Vader.

Eliminating those early scenes with Biggs probably improved the overall pace of the picture. It also gives Garrick Hagon the distinction of being the Canadian who was edited out of Star Wars.

* * *

FORMER FILM STUDENT George Lucas is known to be a fan of National Film Board director Arthur Lipsett. He is said to be especially fond of Lipsett's mind-bending short subject, 21-87 (1963).Lucas also is fond of using cinematic quotations in his screenplays. In 1973's American Graffiti, for example, John Milner's automobile licence number is THX 138. The name of Lucas's first feature film was, of course, THX 1138 (1971).

In Star Wars, when Princess Leia (Carrie Fisher) is a prisoner aboard the imperial battle station Death Star, her cell number is 21-87.

* * *

WHEN A PICTURE BECOMES as popular as Star Wars, filmgoers often try to second-guess the filmmaker. To play the game, all you have to do is keep your eyes and ears open for "bloopers" in the movie.According to slip-up spotters, the most glaring error in Star Wars occurs during the famous Cantina sequence. As you remember, Luke and Obi-Wan "Ben" Kenobi (Alec Guinness) are looking for a pilot to take them to Alderaan. They're introduced to Han Solo (Harrison Ford), the master of the Millennium Falcon.

Solo is proud of his Falcon. "It's the ship that made the Kessel run in less than 12 parsecs," he tells them.

Science-savvy sci-fi fans groaned when they heard that. Parsecs measure distance, not time. It was like hearing an Air Canada pilot boast that he'd made the Toronto run in 2,500 miles.

The line stimulated controversy out of all proportion to its real importance. Arguments and counterarguments filled the fan press, and some remarkable theories (complete with some tortuous mathematical "proofs") have been proposed to explain away Lucas's apparent lapse.

Earlier this year, Lucas was moved to issue a rather snappish statement. "The use of the word 'parsec' by Han Solo in the Cantina scene is definitely not a mistake on my part," he said. "This unusual use of the word 'parsec' was pointed out to me by (author) Alan Dean Foster and several other science-fiction writers before I started shooting the film.

"It was also pointed out to me by Harrison Ford, Mark Hamill and several other actors, and by many members of the crew on numerous occasions before the scene was actually shot. I have no further comment to make as to why it was there."

The line, Lucas insists is deliberate. What he means is that Solo's blooper is there to make a dramatic, not a scientific, point. You don't need mathematics to prove it, either.

Apply Ockham's razor. The scene is set in a barroom. Although Luke and Ben have come there looking for a pilot, Han just dropped by for a drink. He's there taking his mind off his troubles.

Anyone who's ever sat in on a conversation in a beer parlour will recognize the symptoms. Full of bravado and booze, Solo slips up. He's drunk.

Immediately after he speaks the line, the camera cuts to Ben's reaction. The older man has Solo's number, something made obvious in the knowing glance he directs at Luke.

In making Star Wars, George Lucas made very few mistakes. Han Solo's braggadocio is not one of them.

* * *

A FILM SCRIPT GOES through many drafts before the cameras roll. We're told that Star Wars went through at least five.In the second draft, the hero was a heroine. Before coming up with farmboy Luke Skywalker, writer/director Lucas plotted out the story of a teenaged princess who enlists the aid of a middle-aged adventurer named Han Solo to free her imprisoned brother. It was sort of like True Grit in outer space.

It is interesting to speculate on where he got the idea, on what his heroine might have looked like or on how she might have dressed. She might have resembled the young woman with the purposeful look in the photo accompanying this article [in its original 1979 print publication].

It was taken in 1976, before Star Wars went into production, and was used to illustrate an April Playgirl Magazine feature on "The New Hollywood Women.'' It shows us a woman who is not an actress but "the most sought after editor in film today."

Her name? Marcia (Mrs. George) Lucas.

Together with Paul Hirsch and Richard Chew, she cut Star Wars. Together with them, she won Oscar honours for the best film editing of 1977.

* * *

FASHION FOOTNOTE: In The Empire Strikes Back, the Star Wars sequel scheduled to open here May 25, 1980, Princess Leia will sport a new and different hair style. The above is are restored versions of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1977 and a Sunday Magazine feature published in 1979. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: In no time at all, Star Wars the movie became Star Wars the phenomenon, and much nuttiness ensued. (For example, in recent years, in a number of countries, a statistically significant number of people have declared "Jedi" to be their religion of record on official census forms.) Books have been written and stories have been told, among them the various items I included in my 1979 Sunday Magazine feature restored above. Sadly, the one thing I could not restore was that fascinating Playgirl Magazine photograph of Marcia Griffin Lucas. Despite my best efforts, I was unable to find the picture online and, though I may have a copy of the actual magazine stored somewhere in the garage, locating it will require some serious home archaeology. George and Marcia parted company in 1983. Following a reportedly "bitter" divorce, Lucas seems to have written his ex-wife and her influence out of his official Star Wars recollections. Among those offering a more comprehensive consideration of her story is Michael Kaminsky, author of the 2008 book The Secret History of Star Wars. His online essay In Tribute to Marcia Lucas

See also: My review of The Empire Strikes Back (1980), my review of Return of the Jedi (1983), and my 1980 interview with Star Wars producer Gary Kurtz.