Sunday, April 14, 1974.

THE WOLFPEN PRINCIPLE. Music by Don Druick. Written and directed by Jack Darcus. Running time: 96 minutes. Mature entertainment.

ALONG WITH COLOURED EGGS and chocolate rabbits, the Easter weekend brought with it a new Vancouver-made feature film. Launched without the benefit of searchlights or champagne, it's nonetheless a national premiere.

Shot and being shown in 16 millimetre, The Wolfpen Principle is the work of artist-director Jack Darcus. His third low-budget feature, it is focused on the emotional problems of decidedly anti-heroic characters.

The beautiful photography and haunting score give it a thoroughly professional feeling. What it suffers from, though, are moments of thematic ambivalence.

In his screenplay, Darcus constructs an original metaphor for personal freedom, one summed up in the Wolfpen Principle: "The cost to the wolves caged is the price paid by their keepers."

Around this idea, he offers the story of a pair of wolf worshippers who see in the caged creatures a reflection of their own problems. One of them is aging Henry Manufort (Vladimir Valenta), a lumpishly ordinary manager of a Vancouver movie house (10th Avenue's Varsity Theatre).

A desperately unhappy man, Manufort has longed for escape ever since his internment in a Second World War concentration camp. An immigrant with a still-pronounced accent, he is chronically ill at ease.

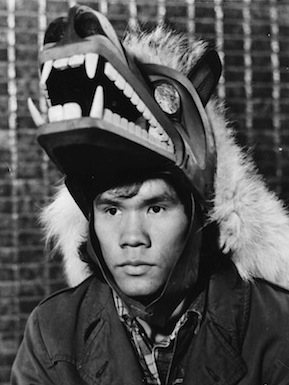

His kindred spirit is young John A. MacDonald Smith (Lawrence Brown), a Pacific coast Indian who believes that the penned wolves are the very creatures who once roamed freely around the village of his birth. Smith is a man with a mission.

Tenaciously clinging to "the old ways," he has come to the city to free the wolves from Vancouver's Stanley Park Zoo. He has come to know of Manufort's obsession with the creatures because both share the habit of visiting the wolfpen in the dead of night.

As a result, the native boy decides to involve the overweight immigrant in his mad scheme. The film is made awkward by the fact that Darcus decided to develop his serious metaphor within a comic framework.

As Manufort's personal depression deepens, the world around him becomes more and more absurd. As his story unfolds, the doleful principals seem less and less a part of the film they're appearing in, a picture in which the supporting roles are all played for laughs.

Darcus provides the morose Manufort with a dumb, doting wife (Doris Chillcott) and a pair of bickering in-laws (Tom Snelgrove and Alicia Ammon), her elderly parents. What he fails to provide is a suitable dramatic explanation of how his Slavic-accented hero became part of a stereotypical Anglo-Saxon family.

What is clear, though, is that Manufort feels out of place.

Naturally his wife is concerned, and her concern leads to her death. The dramatic force of that event is muted by the fact that not only is Manufort already despondent, but her death is the prelude to a sharply satirical funeral, a scene that is both the comic highlight and the most mood-jarring scene in the film.

The film's dramatic weight falls on Vladimir Valenta's broad shoulders. An expatriate Czech actor now living in Canada, he really looks like one of life's victims.

Valenta ably projects a combination of self-pity, desperation and despair, giving Manufort the look of a man seeking someone or something to lead him out of himself.

Lawrence Brown is less convincing as his wilderness guru. His peevishly threatening performance lacks the mystic conviction of the true believer. As a result, I had difficulty believing in his stated fear of becoming "a city Indian."

The film's good looks are in large measure due to the effective night photography of Hans Klardie and Terry Hudson. Its best moments are enhanced by Montreal-born composer Don Druick's effective score.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1974. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: In the story of feature filmmaking in B.C, the dozen years between 1963 and 1975 was a period of excitement and experimentation. Faced with indifferent official support and little encouragement from the distribution establishment, 10 independent talents managed to direct a first feature. Only three completed a second, while just two went on to create a body of work. South African-born Larry Kent was the first to do it. Remembered by Dreaming in the Rain author David Spanner as "the founding father" of the city's independent film movement, Kent produced three features — 1963's The Bitter Ash, Caressed (1964) and When Tomorrow Dies (1965) — before relocating to Montreal. To date, he has 13 features to his credit.

Vancouver-born Jack Darcus released his first feature, Great Coups of History, in 1969. I've always considered him the more interesting of the two. In 1999, when asked to contribute a Darcus profile to The Encyclopedia of British Columbia, I wrote a brief item that described him as an auteur. Together, the eight feature films listed in that profile offer a distinctive look at 30 years of the West Coast experience. Deserters, the 1983 feature that the Cinémathèque will screen next Monday (February 29), recalls a time when Vancouver was a haven for U.S. draft resisters. Jack Darcus turns 75 today (February 22).

See also: Writer-director Sandy Wilson's 1985 debut feature My American Cousin is the B.C. feature being screened tonight (February 22) at the Cinémathèque. Its sequel, American Boyfriends, was released in 1989.