Tuesday, April 17, 1973

JOURNEY. (French language title: Detour.) Music by Luke Gibson. Written, produced and directed by Paul Almond. Running time: 88 minutes. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. classifier's warning: human and animal sex; birth and slaughter of farm animals.

DROWNING PERSONS, IT IS commonly believed, see their entire lives flash before their eyes. At the last possible second, in that moment before permanent darkness falls, the mind explodes in a final blaze of light, illuminating a lifetime of stored memories, thoughts, feelings and ideas.

But how long is a moment?

How much can a moment contain?

To the filmmaker, a moment is a flexible thing. It lasts as long as he wants. In the hands of a master magician, the movies really do become a magic lantern, capturing the elusive shadows of the mind, and fixing them upon the screen.

With Journey, his third theatrical feature, Montreal cine-artlst Paul Almond enters the circle of the master magicians. His film, a mythic journey of inner discovery, enters the mind of a nameless young woman (Genevieve Bujold), and records her complex moment of final review.

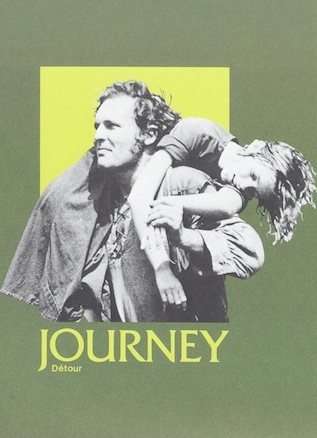

Her reverie — and the film — begins with her rescue from a river by a leather-vested woodsman (John Vernon). Draping her across his shoulders, he carries her through the forest to Undersky, a self-contained community of fewer than a dozen souls hidden away in the Quebec wilderness.

More than half drowned, she convalesces fitfully. In brief moments of consciousness, she becomes aware of her surroundings.

When she finally wakens, she finds that the random images flickering through her mind have organized themselves into a vision of the pioneer past.

A gentle, clear-eyed people have become the population of her world, a people dressed in rustic homespun. Living together in a connected series of log cabins, they busy themselves with clearing the land, tending the livestock and crops, creating their own tools and carving out a life in harmony with the rhythms of nature.

Mute — perhaps still in a state of shock — she learns that her rescuer is called Boulder. When she offers no name for herself, he names her Saguenay, after the river from which he drew her.

From him, she learns that every member of the commune has a given name not his or her own, but representative of their life within the community.

Saguenay is a woman caught within a dream. Like any dreamer, she is slowly discovering its dimensions, and its direction, and wondering at its purpose.

Slowly, too, the audience is making the same discoveries and wondering about the same things.

In Journey, Almond demonstrates a superb cinema craftsmanship, and his almost total control over his concept and its mood. His film not only has the look, but the shape, feel and sound of a dream.

A lesser director would have been happy with a display of photographic pyrotechnics, a combination of Vaselined lenses, tricky distortions and trippy gimmicks, all underscored by searing strings or Moog noodling.

Not Almond. His Journey is guilty of no such distractions.

Keeping the special visual effects to an absolute minimum (there is a momentary slowing of the camera speed at the dramatic centre of the film), he builds mood through the overall structure and content of his story. It is a tale that unfolds through Saguenay's eyes, eyes that see sharply but without clear understanding.

She emerges from her coma bit by bit, catching clear impressions of faces and activity before slipping back into blackness. Almond's cinematographer, Parisian cameraman Jean Boffety, reproduces the same effect for the audience, offering us only as much information as Saguenay has.

Set decorator Ann Pritchard builds a complete world at Undersky, a place that has the handcrafted look of a real backwoods commune. To people it, Almond has selected a cast that might well be a collection of genuine communards.

Or they could be 18th century frontiersmen. As Saguenay awakens, she has no idea where she is, nor does she really know when she is. Is her story set in the past or the present?

The audience is caught in the dream with her, fascinated but unable to demand answers to the obvious questions. Like all dreamers, she is dimly aware that she is dreaming, and that her questions eventually will be answered.

She (and the audience) have the sensation of being carried along familiar mythic paths, and are filled with a sense of dread, fearing the dream will turn into a nightmare.

All of these are, of course, effects that the fllmmaker wants to create. And create them he does, probing as deeply into the North American psyche as Ingmar Bergman does the Scandinavian.

Like Bergman, Almond ultimately sounds universal chords. Unlike Bergman, he builds his drama from the experience of this continent and our own people.

Comparisons can be drawn to other films. Robert Enrico's award-winning 1962 short, An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge, probed the final moment experience of a U.S. Civil War spy as he drops from the scaffold. He experiences, quite naturally, a reverie of escape.

Saguenay, too, looks for escape, but hers is to a mythic past hidden away like the Shangri-la of Lost Horizon (the 1937 Lost Horizon, that is, not the musical travesty [1973] currrently on view).

Her journey is not unlike Dorothy's in the Wizard of Oz. Though she conjures up Undersky (as Dorothy created Oz), like Dorothy she wants only to escape from her dream and return to her own world.

Unlike the wizard's tale, Journey is not for kids. In context, It contains a rather disturbing, though inexplicit, bout of lovemaking, a natural, completely explicit mating of a bull and cow, a somewhat bloody calving, and a very bloody bit of hog butchery.

Jarring to the unsuspecting, each of these scenes is a natural part of the film, and handled with rural honesty and straightforwardness.

An arresting and involving film, Journey engages both mind and emotions. It is a moment well worth the 88 minutes it takes to live through it.

* * *

HARSH REALITIES: Without going into yet another discussion of the sad state of Canadian fIlm distribution, let me report that Journey did not perform well at the weekend box office. On Friday, after a one-week run, Odeon theatres will replace it at the Dunbar Theatre with the well-worn 1972 American feature Sounder.Odeon has no plans to bring it back to Vancouver. Ever.

Journey is the best film that I have seen in a long time. It is a genuine film fan's film, the sort of movie that makes an evening out a lasting experience. It will be here for three more days.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1973. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Filmed in Saguenay, Quebec, in 1972, Journey had a troubled distribution history. Though I saw (and reviewed) the picture during its brief commercial release in Vancouver in mid-April 1973, the Internet Movie Database (IMDb) lists its U.S. release date as August 25, 1976, with an October 6, 1978, release in Canada. As a result, Journey remains one of the least-seen of Saskatchewan-born John Vernon's more than 50 feature film roles. Like many of Canada's versatile character actors, Vernon served his apprenticeship at the Stratford Shakespeare Festival (1956-1962), and on CBC television, where he played the title role in the influential mid-1960s series Wojeck. No villain, Dr. Steve Wojeck was a crusading Toronto coroner, the star of the show that inspired the eight-season U.S. series Quincy, M.E. (1976-1983). Vernon's first Hollywood feature was a showy supporting role in director John Boorman's 1967 action hit, Point Blank, playing the bad guy that audiences loved to hate. Or, as Animal House director John Landis understood, that audiences loved to laugh at. Vernon's turn as the Delta-hating Faber College Dean Vernon Wormer won him the starring role in the single-season ABC-TV series Delta House (1979). His was an acting career that spanned more than 50 years, and was bracketed by voice performances. Shortly before his death in 2005, he recorded the dialog for the Nohrin Judge character in the animated feature Delgo (released in 2008). His feature film debut had been as the voice of Big Brother in director Michael Anderson's 1956 adaptation of 1984. In between, he was heard in such big screen cartoons as1981's Heavy Metal and more than a dozen animated TV series. Fun fact for Marvel comics fans: John Vernon was the first actor to play Tony Stark, providing the character's voice in the 1966 Iron Man TV series.