Sunday, November 9, 1986.

TAI-PAN. Written by John Briley and Stanley Mann, based on the 1966 novel by James Clavell. Music by Maurice Jarre. Directed by Daryl Duke. Running time: 125 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: Occasional violence and nudity.

SOME THINGS NEVER CHANGE. From DeMille to DeLaurentiis, all the great good/bad movies contain a judicious mixture of bosom, bondage and bombast.

In adapting James Clavell’s doorstop novel Tai-Pan to the screen for producer Raffaella De Laurentiis, Vancouver-based director Daryl Duke has applied the time-honoured formula to produce this year’s golden gobbler, an example of epic awfulness that can take its place alongside such classic clunkers as Mandingo and The 10 Commandments.

Based more or less on the story of Hong Kong, Duke's period piece opens with the March 1839 expulsion of foreign traders from the Chinese city of Canton. The imperial edict is issued to the European community’s leader, a Scot named Dirk Struan (Bryan Brown) by the Emperor’s incorruptible Commissioner Lin (Zhang Jie).

Struan is known as Tai-Pan, which in context means “the main man.” An opium merchant, he and his companions are being expelled from the mainland for their drug dealing. “Lin orrr no Lin,” the great white pusher vows, with his highland burr dialled up to ten, “Noble House will live forrr 200 yearrrs!”

And so it’s on to “destiny’s gift to Tai-Pan," the island of Hong Kong, where Struan involves himself in commercial and personal feuding with Tyler Brock (John Stanton), the neighbourhood’s No. 2 merchant, for the rest of the movie.

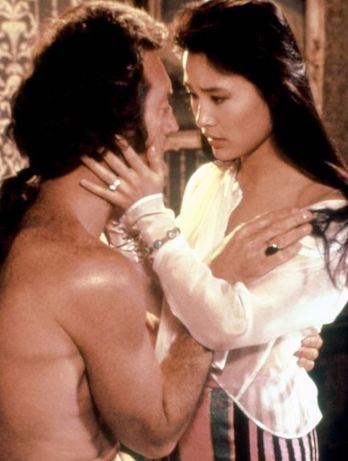

When not swashbuckling, Struan enjoys the company of May-May (Joan Chen), the kittenish granddaughter of his Chinese associate Jin Qua (Cheng Chuang), whose duties include teaching her barbarian lover "civilized" ways.

In condensing Clavell's florid narrative into two hours of screentime, writers John (Gandhi) Briley and Stanley Mann have reduced the story to a selection of melodramatic highlights. As a result, a lot of characters appear suddenly, declaim briefly, then disappear again.

My favourite was Mary Sinclair (Katy Behean), first seen at the ceremony that marks the founding of the colony. If memory serves, she is introduced as a missionary’s daughter.

When we next see her, she is nude and in bed with a wealthy Chinese merchant. “By the Sweet Jesus, I’m lost," Struan expostulates. “This is not the Marrry Sinclairrr that I knew!”

Mary, it seem, is revealing her secret life to Tai-Pan to prove that she can help him commercially. “You stopped my father from beating me,” she says by way of explanation. “But not my brother from 'comforting' me.”

This is not dialogue, it’s cartoon captioning. Recognizing, perhaps, the futility of taking this sort of thing seriously, Duke phones in his direction and lets the silliness escalate.

Laugh if you like. When Struan’s adult son Culum (Tim Guinee) arrives with the news that “the plague has struck Glasgow again," it’s hard not to.

Laughter, after all, is the only response to a cast that grins, grimaces and glowers its way through a plot thick with secret meetings, brothel visits, public celebrations and fancy dress balls.

Laugh, and even Australian actor Brown’s lifeless performance is bearable. Without laughter (to paraphrase Star Trek engineer Montgomery Scott), the audience cannah take much morrrre Tai-Pan.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1986. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Not Daryl Duke’s finest two hours, Tai-Pan could at least lay claim to being the first western feature filmed in post-revolutionary China. His cast and crew were on location from mid-October 1985 to early March 1986. Five months later, on July 28, Bernardo Bertolucci called “action” on his own made-in-China epic, The Last Emperor. Tai-Pan, a singularly forgettable film with but a single real achievement, never crossed my mind when I posted my 1987 review of Bertolucci’s picture, and I noted its claim to the historic first. What the Italian auteur’s diplomacy had actually managed was permission to film in Beijing’s Forbidden City, an impressive first all on its own.

That said, I’m pretty sure that the distinction of being the first western filmmaker allowed into post-revolutionary China belongs to National Film Board of Canada director Tony Ianzelo. An exchange program negotiated between Ottawa and Beijing resulted in his 1980 documentary features North China Commune and North China Factory. Duke’s access may well have been due to Ianzelo’s pioneering work in the Peoples Republic.

See also: Following the release of his 1973 feature Payday, DarlyDuke sat down with me for an interview on the future of Canadian film.