Saturday, March 10, 1973.

PAYDAY. Written by Don Carpenter. Music by Ed Bogas, Tommy McKinney, Shel Silverstein, Ian Tyson, Sylvia Tyson. Directed by Daryl Duke. Running time: 103 minutes. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: coarse language and sex.

ESSENTIAL TO THE IDEA of America — more essential, indeed, than either Washington, Lincoln, Jesse James or Al Capone — is the idea of the road. Throughout U.S. history, the road has been almost an end in itself, a metaphor for freedom, progress, beauty and betterment.

In a land as geographically immense as America, the road does not merely connect places, it is a place in and of itself. The road has its own history, culture and mythology.

And it has its people, a population composed of the self-reliant, the self-doubting and the just plain selfish.

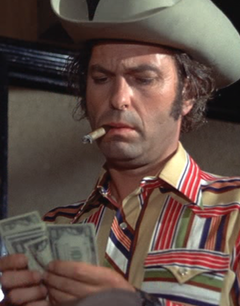

Maury Dunn (Rip Torn) is one of them, as ugly a customer as ever rode an interstate, and as tragic. Dunn is the central character in Payday, former CBC producer Daryl Duke's first theatrical feature.

Dunn is a second-rate country and western singer. His story is a blunt and brutal tale of road life, a film powerful enough to throw the myth into a skid and leave a bloodstain on the blacktop.

Although he's been in the business just as long as Johnny Cash or Buck Owens, he’s never been good enough to grab a "big break." The film opens with him still on the road, the star of one-night stands in highway road houses in the Deep South, making a buck where he can, raising hell when he can.

After his final set, while his gnomish manager Clarence McGinty (Michael C. Gwynne) is collecting the take, Dunn finds time to leave wide-eyed Sandy (Linda Spatz), an autograph-seeking fan, with a more personal remembrance of the show.

While Dunn is tucked away in a basement with one country girl, Bob Tally (Jeff Morris), his slower-moving sidesman, is busy talking another into an after-hours motel party. It is through the eyes of this second girl, Rosamond McClintock (Elayne Heilveil), a fresh-faced dime-store clerk who comes complete with ringlets, dimples and a look of fascinated terror, that the Dunn roadshow is seen for what it is: a demonic ritual in which in which every member of the entourage is possessed in one way or another by the presiding devil, Maury Dunn.

Director Duke, previously one of the CBC’s most creative and controversial producers, knows the value of a visual image. He surrounds his star with a sea of expressive faces, the kind of actors who speak their roles without uttering a line of dialogue. When they do voice their lines, from Don Carpenter’s lean and natural-sounding screenplay, the authenticity is outstanding.

Like the script, the music in Payday is original, with credit going to humourist Shel Silverstein, who contributed four songs. The “complete world” of Maury Dunn, they are performed by Torn with his backup group The Dandies (bluegrass musicians Richard Hoffman, Bobby Smith and Dallas Smith, otherwise known as The Boys from Shiloh).

The cast, which includes Ahna Capri as Dunn’s buxom mistress Mayleen Travis, and Cliff Emmich as his loyal driver Chicago, give the film the look and feel of raw realism.

At Payday’s centre, Torn (who often shares with Marlon Brando the weighty accolade “America’s finest actor”) gives Dunn the combination of outward simplicity and interior complexity upon which everything is focused. His performance is the wellspring of the film’s power.

Duke’s picture records two days and nights of Dunn’s tour, a series of incidents that add up to a life, and a way of life. A contemporary morality play, Payday assesses its value and leaves the audience to decide whether it’s worth the price.

Road life may not be. This movie’s vision of it, though, certainly is.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1973. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Did I mention that Daryl Duke was once my boss? As noted in the introduction to this posting, he was the founder, president, CEO and chairman of the board of Vancouver’s CKVU-TV. In 1976, his partner Norman Klenman hired me to play a movie critic on The Vancouver Show. When the station launched on Sunday, September 5th, there I was on the set with hosts Mike Winlaw and Pia Shandel, offering my reviews of Drum, Stay Hungry and A Small Town in Texas. In his 2006 tribute to Duke, Charles Campbell recalled that he created CKVU “to honour” his home town. That effort involved spreading a lot of money around to bring local celebrities, community leaders and newspaper byliners into its studio. It was great while it lasted . . . which was about four months.

The largesse came to an end in the new year, and I was among the freelancers shown the door. I might have followed the CKVU business story more closely, but in the spring of 1977 I was diagnosed with cancer. For the next year, my attention was focused on survival, a process that involved two operations and some brutal chemotherapy. The drama involving Duke’s embattled Western Approaches Limited was just not relevant to me any more.

As a result, I have no idea what really happened behind the scenes at CKVU. Although the Internet makes it possible to construct a timeline of sorts, it appears that no one has set down the story either as a memoir or corporate history. Until someone takes up that task, we’ll not know how or why Duke’s dream for local television broadcasting died.

See also: Following the release of his 1973 feature Payday, DarlyDuke sat down with me for an interview on the future of Canadian film. Also included in the Reeling Back archive is my review of his 1986 made-in-China epic Tai-Pan.