Frlday, March 9, 1979

NORMA RAE. Written by Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank Jr. Suggested by the book Crystal Lee: A Woman of Inheritance (1975), by Henry "Hank" Leifermann. Music by David Shire. Directed by Martin Ritt. Running time: 110 minutes.

NORMA RAE'S BOYFRIEND is a real charmer. "You hick!" he tells her after an evening at the local motel. "You got dirt under your fingernails, and you pick your teeth with a matchbook."

Norma Rae Webster is not what you would call glamourous. A second-generation factory hand in a small-town cotton mill, she has two children and no husband. She puts out because, well, hell, what else is there to do after work, anyhow.

This morning Norma Rae got angry. Her mother, with a lifetime of service to the mill, is going deaf and the company doctor doesn't really give a damn. In a funk over it all, Norma Rae tells her motel lover that she's breaking off the affair. He gives her a bloody nose for her trouble.

Appearances to the contrary, Norma Rae is not stupid. Though she's been used, bruised and abused for about 30 years, she still has her anger and a sharp mind. And now she is ready for a little consciousness-raising.

Sally Field, 33, is trying to shake her charmer image. Think of Gidget (1965), The Flying Nun (1967) and The Girl with Something Extra (1973), and the word that immediately comes to mind is "cute."

Six years ago, Field decided that "cute" wasn't good enough. Instead of contracting for yet another stereotypical TV series, she accepted the role of a slatternly southerner in a film called Stay Hungry, a role that came complete with some crude talk and a semi-nude scene. Her performance was about the only good thing in the picture.

Her relationship with Burt Reynolds — so far they've appeared together in three films and countless fan magazine articles — diverted attention from her development as an actress for the last little while. Now, though, with Norma Rae, Field shows that she is a capable and effective dramatic performer.

Again, Field is better than the movie she's playing in. Norma Rae, the film, is neither as tough nor as committed as its star. It suffers from divided dramatic loyalties.

On one hand, it is the story of how the textile workers organized their union. But, because director Martin Ritt has a deep-seated fear of being too polemical, it is also the story of a woman who seizes an opportunity to fulfill her own personal potential.

In doing so, she finds herself deeply involved with two men. In one instance, the relationship is platonic. Reuben (Ron Leibman), the street-wise New York labour organizer, introduces her to poetry and purposefulness. "I think you're too smart for what's happening to you," he says.

In the other, it is romantic. Sonny (Beau Bridges), a fellow factory worker, provides her with a home and emotional support. Recognizing something special in her, he asks her to marry him.

All things considered, it might have been better if Norma Rae had thrown herself into something a little less compelling, something like Tupperware sales, baton twirling or, perhaps, fundamentalist religion. That way, we could have concentrated fully on her story and not had to worry about the background details.

Union organization, however, is a diverting subject, especially today [1979] in this neighbourhood. Ritt, for his part, works hard to show us just how oppressive conditions in a modern cotton mill can be.

The air inside the windowless fortress of a factory is thick with disease-inducing plant fibres and teeth-rattling machine noise. Add to that a level of racial tension, some sexual exploitation and minimum-wage pay packets, and a whole new movie begins to take shape.

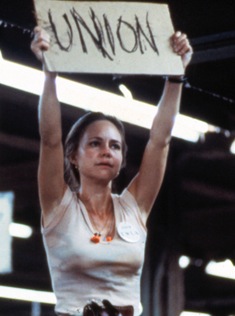

Ritt, whose films include a powerful tale of coal-field labour conflict (The Molly Maguires; 1969), has tied the success of his characters to the success of the workers' certification drive. It is a rite of passage that Norma Rae must go through to find herself.

In doing so, though, the director must portray the union/management conflict in overly simplistic terms. It becomes little more than a clash between good and evil, an idea more appealing than it is accurate.

Union partisans will come away comforted. Field fans, and I guess I'm one of them, are in for a real treat, though.

Up front and top-billed, Sally Field proves that she can be both cute and compelling, an actress capable of carrying a difficult picture all on her own.

The above is a restored version of a Vancouver Express review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1979. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: In taking Martin Ritt to task for subordinating his social message — the value of union organizing — to dramatic character development in Norma Rae, I was reflecting the time and place of this particular review's publication. In March 1979, the union to which I belonged was into the fifth month of a grinding eight-month strike against Vancouver's Pacific Press newspapers. During the dispute, the workers' Joint Council published The Vancouver Express, an interim paper put out by the idled printing, engraving, press, mailing room, advertising and newsroom staff. We all contributed by doing what we did, in my case covering the movies. Part of that coverage involved an interview with the picture's star, Sally Field, who had some interesting things to say about campaigning for the Academy Award that she would, in fact, win a year later (1980).