Sunday, December 8, 1991

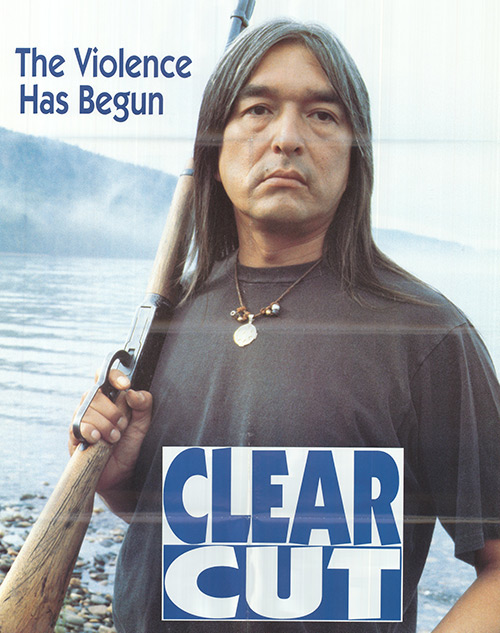

CLEARCUT. Written by Rob Forsyth. Based on M.T. Kelly's 1987 novel, A Dream Like Mine. Music by Shane Harvey. Directed by Richard (Ryszard) Bugajski. Running time: 100 minutes. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. Classfier’s warning: some very gory violence, very coarse language.

THE EARTH BLEEDS.

Peter Maguire (Ron Lea) sees it — rivulets of red against grey granite, flowing slowly over sacred glyphs. He sees it in the darkness of the sweat lodge, a vision of his own inner rage.

And now, on the shore of a Northern Ontario lake, men bleed. Two provincial police officers are dead and a logging company executive is being skinned alive.

"You dreamed anger," sad-eyed Ojibway tribal elder Wilf Redwing (Floyd Red Crow Westerman) reminds Maguire. "Your anger is real."

The anger is real. Last week [November, 1991], European environmentalists turned their attention to Canadian logging practices, described in the British press as a "chainsaw massacre."

This week, Polish director Richard Bugajski's feature Clearcut expresses the rage in mythic terms. An adaptation of M.T. Kelly's 1987 novel, A Dream Like Mine, Bugajski's wilderness drama looks into the heart of one wimpy Canadian do-gooder and finds unexpected violence.

A Toronto lawyer specializing in liberal causes, Maguire represents the people of the Heron Portage Reserve in their fight against the local pulp mill. He's in despair because they are losing.

Following his vision in the sweat lodge, Maguire is approached by a man named Arthur (Graham Greene) who asks, "What do we do now?"

"Blow the mill up."

"Okay," says Arthur.

"Tie the mill manager up and skin him," Maguire adds.

"Do you really think that's a good idea?" says Arthur, with childlike innocence.

Drawing upon traditional Indian beliefs, Bugajski creates a shock thriller that falls somewhere between Joseph Campbell and David Cronenberg. Arthur is Maguire's rage made flesh, a force both frightening and fascinating.

Once loose, he insists upon kidnapping tough, uncompromising mill manager Bud Rickets (Michael Hogan). Horrified, Maguire alternates between urging Arthur on and attempting to rein him in.

As played by Greene (Oscar-nominated for his performance as Kicking Bird, "the quiet one" in Kevin Costner's 1990 feature Dances with Wolves), Arthur is a charming, charismatic psychopath. In a showcase role, Greene dominates the screen, moving with ease between witty companionability and terrifying intensity.

As in his 1982 Polish women's prison picture Interrogation, Bugajski is rather too quick to indulge in explicit violence. Too much blood only serves to mute his otherwise-honest plea for justice for Mother Earth.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1991. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Writing in 1948, George Orwell saw the Britain of Nineteen Eighty-Four as a totalitarian nightmare state. The novel’s central character, Winston Smith, comes to believe that “if there is hope . . . it lies in the proles,” the working people ignored by the regime, the poor, the disposessed and the marginalized. Living in 2017, we see Canada (and the egalitarian social democracy that it claims to be) at a crossroads. Technology combined with corporate greed has made Orwell’s dystopian fantasy chillingly real. In our case, though, hope lies in the First Nations. Today, our self-described founding nations — the Europeans celebrating a sesquicentennial — are passionate colonialists. First attached to the English empire, the politically powerful are now desperate to please a mercurial American superstate. They’re happy to preside over a failing nation where deepening inequities enrich a few while creating misery for the many. As gormless political parties scramble for advantage, the time for solving the great issue of human survival, aka the environmental crisis, is rapidly running out.

Opposing the status quo are activist First Nations. Contrary to the premise of legal failure that sets the plot of Clearcut in motion, Canada’s courts increasingly are in sympathy with the cases brought before them. In a unanimous 2014 ruling, the Supreme Court found ““The doctrine of terra nullius [that no one owned the land prior to European assertion of sovereignty] never applied in Canada.” A landmark decision, Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia recognized that the arguments for indigenous sovereignty, indigenous rights and respect for treaties asserted by such grassroots organizations as Idle No More (founded in 2012), have a basis in law. Today (June 21), Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced his government’s intention to rename the annual celebration "National Indigenous Peoples Day," and said it “is working together with Indigenous Peoples to build a nation-to-nation, Inuit-Crown, government-to-government relationship – one based on respect, partnership, and recognition of rights." In response, Assembly of First Nations National Chief Perry Bellegarde said “In spite of the genocide from the residential schools and the colonization and oppression of the Indian Act and the exploitation of the land and territories, everything we have faced in the last 500 years, we're still here as Indigenous peoples.” Or, as I said above, our hope lies in the First Nations.

See also: Reeling Back’s 2016 National Aboriginal Day posting featured director Bruce McDonald’s look at a new generation of First Nations youth, 1994’s Dance Me Outside.