Friday, March 13, 1970.

M*A*S*H. Written by Ring Lardner Jr., based on the 1968 novel by Richard Hooker. Music by Johnny Mandel. Directed by Robert Altman. Running time: 116 minutes. Restricted entertainment.

IT REALLY IS A GRIM world. Some people, like the United States Army and Air Force Motion Picture Services, for example, just can't take a joke.

Their review board took a look at Robert Altman's blood-soaked black comedy M*A*S*H and promptly declared the film "off limits" for all American service installations. The Pentagon does not regard war as a laughing matter.

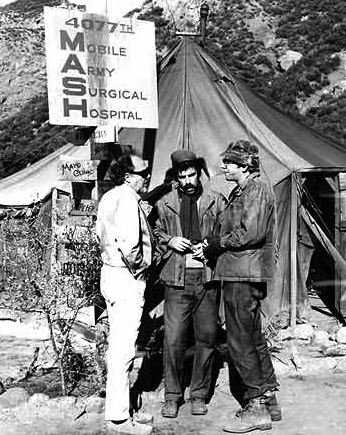

Nor, in fact, do the men of the 4077th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital. Sitting a tight three miles behind the Korean battle lines, their grim mission is saving the spent human shells ejected from the front.

Their canvas-topped operating room is stocked with the best equipment and staffed with the finest doctors that America can provide. The Army's "police action" does its part by heaving up the supply of freshly shattered bodies that keeps the M.A.S.H. unit busy.

It was an American general who once said "war is hell." For an ordinary citizen, however, only one word properly describes that game that nations play — insanity.

Drafted into the midst of the international madness is civilian surgeon Hawkeye Pierce (played by Canadian actor Donald Sutherland). From the moment he lands in Seoul, he has the case diagnosed. It's him against the Army, man to madness.

He finds a solid ally in the hirsute chest surgeon, Trapper John McIntyre (Elliot Gould), and together they turn the loosely disciplined M.A.S.H. station into a madcap medical fraternity house.

Opposition to their unsoldierly conduct comes from the unit's professional militarists, head nurse Margaret Houlihan (Sally Kellerman) and Major Frank Burns (Robert Duvall), a bible-belting, intolerant Southern fundamentalist.

The showdown comes when Burns mistreats an enlisted man. Taking the major aside, Trapper, a captain, smashes his superior officer to the floor with a roundhouse right.

At that moment the base commander appears on the scene. "Put yourself under arrest, captain," he orders half-heartedly.

"Will you get serious," Trapper replies, shrugging off the empty court-martial threat, and heading back to work. Doctors, he rightly reasons, are exempt from the silly toy soldier's rules.

Richard Hooker's book MASH: A Novel about Three Army Doctors, was the Korean war's Catch-22. In it the only rule was survival. Director Altman shows us why, with a faithful picture of the M.A.S.H.-men's own bloody battlefield, the operating theatre.

No Kildare-clean, machine-filled auditorium for the military medics. Altman's doctors work day-long shifts over a succession of nameless torn and bleeding torsos. And, like real doctors, they banter casually with their colleagues while they're doing it.

Off duty, Hawkeye and Trapper throw themselves into their calculated insanity with the same cool professionalism, whether the goal is to establish the naked truth about nurse Houlihan's blondness, to restore a debilitated dentist's sexual potency or to win an inter-service football match.

Director Altman, whose last foray into the abnormal was the Vancouver-made That Cold Day in the Park (1969), makes up for that chilly mistake with M*A*S*H, the funniest sick-joke film since Dr. Strangelove.

From his stars, Sutherland and Gould, he draws the subtle, understated performances so necessary to make the film's outrageous content work.

From screenwriter Ring Lardner Jr., he drew a scalpel-sharp script, as lean and economical as it is anarchic and funny. Lardner's low-key dialogue is as uncompromisingly true-to-life as Altman's operating room.

Lardner's part in the project is tinged with particular irony. As a member of the blacklisted "Hollywood Ten," he spent the Korean war years in the U.S. federal prison at Danbury, Connecticut, jailed for his alleged contempt of that most contemptible tribunal, the U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee.

While serving his sentence, he heard many of his non-political fellow prisoners singing the jingle "I've had gonorrhoea, pyorrhoea, diarrhea, but I don't want no part of that Korea."

Almost a generation later he helped create a medical team to treat "that Korea." The result is an irreverent farce that often coagulates into riotous satire as it bleeds off warfare's madness.

Let loose on a conscript army, M*A*S*H could cause real riots. Maybe that's why the Pentagon fears it.

The above is a restored version of a Vancouver Express review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1970. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: In September 1972, 20th Century Fox spun off a television series called M*A*S*H based on novelist Richard Hooker's characters. I found its debut broadcast disappointingly tepid, and wrote a review in which I predicted that it wouldn't last. I never watched another episode and, after 11 seasons (1972-1983) and 14 Emmy awards, it finally gave up and went away. Of the feature film's cast, Gary Burghoff was the only actor to take his character ("Radar" O'Reilly) to television, reprising the role during the show's first eight seasons. The TV show used film composer Johnny Mandel's lilting "Song from M*A*S*H (Suicide Is Painless)" as its main theme, omitting the vocals with their satirical endorsement of self-slaughter.

See also: The Korean "police action" was the subject of the $46-million epic Inchon (1982), produced by the Korean-based Unification Church to celebrate God's own warrior, U.S. General Douglas MacArthur (played by Britain's Laurence Olivier). Director Robert Altman went on to examine the life of artist Vincent Van Gogh in his 1990 film Vincent & Theo, and offer a satirical look at the modern movie business in The Player (1992).