Tuesday, December 27,1977

MOHAMMAD, THE FOUNDER OF ISLAM, disliked dogs.

Among the other things that displeased him were silk-lined garments, interest charges, painters and poets.

Today [1977], to nearly half a billion people around the world, Mohammad is known as the Prophet. His lack of interest in the arts, as well as his views on idolatry, are reflected in the fact that Islam forbids representation of the Prophet's face, form or voice in any medium.

Producer-director Moustapha Akkad, a Syrian-born Muslim, knew that. Nevertheless, he was determined to tell the story of the Prophet in “a film that (would) educate the non-Muslim masses into the concept of Islam and also aid in the enlightenment of Muslims all over the world."

In March [1977], his movie, the three-hour-long Mohammad, Messenger of God, opened in Washington, D.C. The cause of enlightenment was set back somewhat when 12 gunmen, who identified themselves as “Hanafi Muslims,” took 132 hostages in three separate attacks. Their bizarre list of demands included the closure of Akkad's film on grounds of sacrilege.

Last week the movie was scheduled to open in Toronto. Famous Players Ltd. cancelled the booking when a Muslim community spokesman mumbled darkly about violence that "might occur" if the film was shown. According to the spokesman, the movie violates Muslim religious belief in its depiction of the Prophet.

Rubbish! The Hanafis can perhaps be forgiven. They were nuts.

Toronto's Muslims, on the other hand, have no such excuse. Responsible community leaders have a duty to be in possession of the facts before speaking out.

The film is scheduled to open locally on January 13 [1978]. The matter may be of some concern to Vancouver's own Muslim community, so here are some facts about the production.

Mohammad, Messenger of God, erroneously labelled a “Hollywood film” in some reports, was shot on location in Libya and Morocco. It was made at a cost of some $18 million, money put up by Arab entrepreneurs from their store of petrodollars.

With that much money at stake, Akkad was encouraged to be very, very orthodox. His screenplay, credited to H.A.L. (Harry) Craig, was approved, page by page, by Muslim scholars at Cairo's Al Azzar University.

Mohammad does not appear in the film, nor is his voice heard. As in many films about Christ, his presence is suggested rather than shown. Occasionally we are permitted to glimpse a portion of his walking stick or the back of his camel's head.

Akkad is at pains to point out that at least nine other “life of Mohammad” films have been made in Arabic, all of them using the same workarounds. His film, certainly the most ambitious, was shot in two versions, one in Arabic with Middle Eastern stars, the other in English with European and American performers.

The English version that had its premiere in London's Plaza-1 Theatre last August [1976] stars Anthony Quinn as Hamza, the Prophet's uncle and leader of his warrior legions. Others included in the cast of the English-language film are Irene Papas, Michael Ansara, Johnny Sekka and Michael Forest.

The film seemed decidedly non-controversial to trade-press reporters. Box Office called it "a religious spectacle of high quality." Variety thought it was a "tasteful epic" and noted that "everything on screen bespeaks dedication."

The picture, its title changed to The Message, appears to have played Britain without incident.

"The story," said an Akkad press release sent out while his picture was still before the cameras in Libya, "champions freedom of speech and the rights of the individual." It is indeed ironic that a movie made with such noble motives should arouse such vitriolic opposition.

I hope that Vancouver filmgoers, regardless of their religious beliefs, will show more common sense. The cause of enlightenment is never served by uninformed protests and irresponsible threats of violence.

* * *

Saturday, April 1, 1978.

MOHAMMAD, MESSENGER OF GOD. Written by H.A.L. Craig. Music by Maurice Jarre. Produced and directed by Moustapha Akkad. Running time: 177 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: some violence, may offend some religious groups.

MARX WAS WRONG.

The great guru of international communism, Karl Marx, claimed that religion was the opiate of the masses. He'd have been a lot closer to the truth if he'd attacked religious movies, instead.

Despite the best of intentions, most spectacles like Mohammad, Messenger of God end up being boring bedsheet operas.

The example currently on view was born of one man's dream. Moustapha Akkad, a Syrian-born American with a sincere devotion to his Muslim faith, wanted to bring the epic of Islam to the screen.

Making that job all but impossible is the fact that Islam forbids representations of the Prophet's voice, face or form in any medium. Akkad, to his credit, was eager to take up this formidible challenge.

The result is a film about Mohammad in which the Prophet is neither seen nor heard. Instead, his presence is implied by a subjective camera towards which the actors direct questions, comments and baleful looks.

Not showing Mohammad spares Akkad the wrath of his fellow Muslims. It's no way to make a movie, though — something that Hollywood filmmakers learned many years ago.

Akkad, however, is a man with a mission. He is determined to "educate the non-Moslem masses into the concept of Islam." His sermon begins in the year 610 A.D. in the Middle Eastern city of Mecca, a thriving desert metropolis whose economy is almost solely based on religion.

A spiritual supermarket — 360 gods, no waiting — this Mecca has little use for monotheism or its followers. When Mohammad, a middle-aged camel driver, claims to be "the messenger of God," he is discreetly told to shut up.

He doesn’t. In July 622, the Prophet is forced to flee across the desert to a more hospitable community called Medina. There, the faithful build Islam's first mosque.

At this point, the on-screen heroes are Mohammad's rough-and-ready uncle, Hamza (Anthony Quinn), and Bilal (Johnny Sekka), a former slave who is all for a religion that tells him he is his master's equal.

Cast as villains are the Meccan merchants, represented by the bloodthirsty Hind (Irene Pappas) and her cowardly husband, Bu-Sofyan (Michael Ansara).

Akkad's film quickly falls victim to the curse of all religious spectacles. Though the birth of any new faith is full of passion, drama and intrigue, actors recreating such events usually do so with the look of the lobotomized.

The Meccans, finally perceiving the Muslims as a serious threat, send a force against them and are defeated. Later, in a rematch, the Muslims take a licking. Then both sides call a 10-year truce.

Those two brief battles, sad to say, are the only good things in the movie. Carefully choreographed so that there is no difficulty keeping track of who's who or how the fight is going, they provide the filmmakers with their only opportunity to really cut loose.

The rest of the picture plods along for an endless three hours, pausing from time to time to remind us that "there is no God but God and Mohammad is His messenger." For the faithful, that's probably good enough.

For non-Muslim filmgoers, though, Mohammad, Messenger of God will be just another soporific sandal-flapper.

The above are restored versions of a Province feature and review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1977 and 1978. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Moustapha Akkad’s sincerity was never in question. Born in Aleppo, Syria in 1930, he immigrated to the U.S. at the age of 19 to study filmmaking. He saw the entertainment business as a way to build bridges between people and in 1975, after 25 years of working behind the scenes in film and television, he had the contacts and the credentials to go on location in Morocco and Libya to shoot his directorial debut feature, Mohammad, Messenger of God. (Akkad, who had been inspired by director David Lean’s 1962 epic Lawrence of Arabia, hired that film's Academy Award-winning composer Maurice Jarre to write the score for his picture. Jarre was rewarded with another Oscar for the effort.)

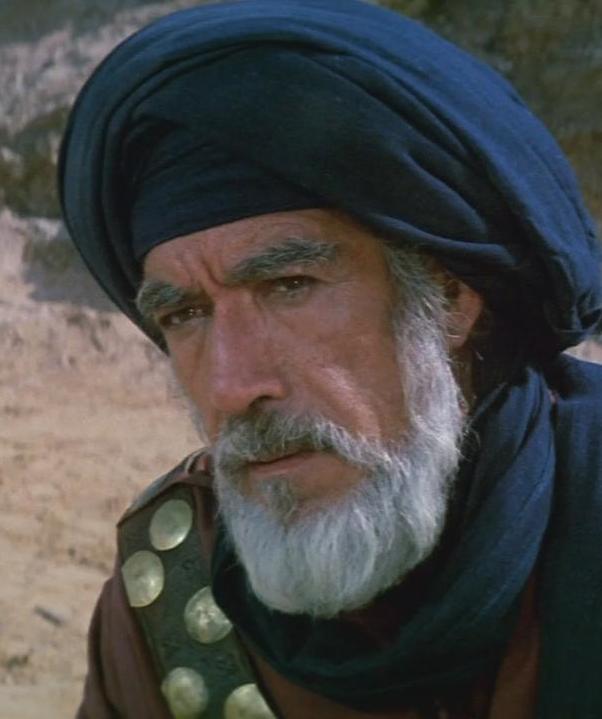

During its production, Mohammad, Messenger of God was the subject of controversy in the Islamic world and, as noted in the above feature story, the subject of violent protests upon its release. Though well received in Iran, it was not a commercial success worldwide. Returning to Hollywood, Akkad achieved fame as the producer of the Halloween film franchise. Following the huge success of director John Carpenter’s 1978 Halloween, Akkad made his second attempt at historical reconciliation, 1980’s Lion of the Desert. Shot on location in Libya, it told the story of freedom fighter Omar Mukhtar’s battle against the Italian fascist army that invaded that North African nation in the 1930s. Akkad again hired Anthony Quinn, casting him in the title role. This time there was controversy in Italy, where the picture was banned for dishonouring the army.

Akkad was no quitter. In 2005, he was working with Sean Connery, developing a feature about Saladin, the legendary 12th-century sultan who led the fight against the Christian crusaders. Having had a hit in 1975 playing Raisuli, the Moroccan brigand in John Milius’s The Wind and the Lion, Connery was sympathetic to Akkad’s screenplay. Their collaboration ended with Akkad’s death in September 2005, one of nine people killed in a suicide bomb attack on the Grand Hyatt hotel in Amman, Jordan. Although news reports written at the time identified him as the producer of the Halloween horror films, later tributes point out the tragic irony in a terrorist act ending the life of a man who made feature films designed to promote sectarian understanding.

In 2015, Iranian director Majid Majidi’s Muhammad: The Messenger of God was screened in Tehran and, later, at the Montreal World Film Festival. Designed as the first in a new biographical trilogy, Majidi’s three-hour feature honours the prohibition on depicting the Prophet by telling the story of his first 13 years in scenes shot only from his point of view. And yes, controversy ensued, with calls for the film to be banned in a number of Sunni Arab countries.

See also: A decade later, footage from Moustapha Akkad’s 1976 theatrical feature was used in the audio-visual examination of Islam that was seen in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s pavilion during Vancouver’s Expo 86.