Wednesday, July 21, 1976

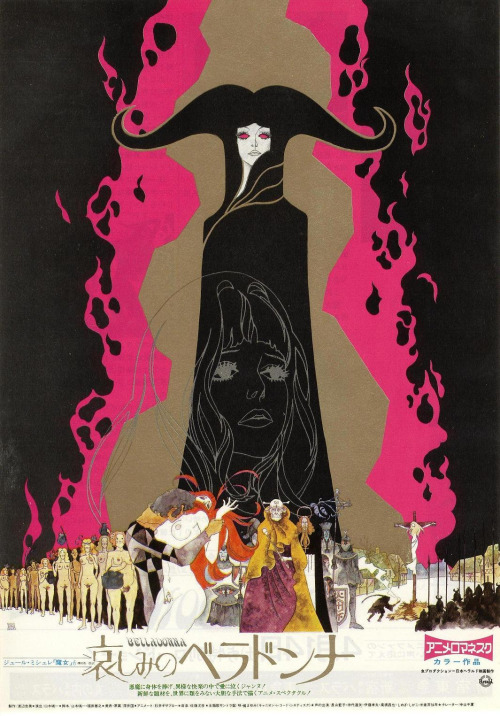

BELLADONNA (original Japanese title: Kanashimi no Belladonna). Feature-length animated fantasy written and directed by Eiichi Yamamoto. Music by Masahiko Sato. Running time: 93 minutes. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: "frequently suggestive." In Japanese with English subtitles.

HAND-MADE, FRAME BY painstaking frame, animated cartoons are the most artistically demanding of film forms. For that reason animators have a tendency to pitch their products to the ages, counting on posterity rather than the immediate payoff to ultimately provide them with a profit.

Walt Disney, the man who "invented"' the feature-length cartoon, set the pattern in 1937, delving into the timeless world of fairy tales to make a movie that would stand the test of time. In its most recent re-release for Christmas, 1975, his Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs had lost none of its original magic or charm.

It's not so surprising, then, that modern Japanese animator Eiichi Yamamoto should look to a faraway time and place for his inspiration. What is surprising is the story he ultimately chose to tell.

For filmgoers accustomed to think of cartoons as "kid stuff," his Belladonna [also known as Belladonna of Sadness] will be shocking. Animation sophisticates, on the other hand, should be totally fascinated.

Belladonna is the name of a plant. Also known as deadly nightshade, it grows wild in Europe and is the one from which the drugs hyoscine and atropine are derived. Belladonna, the film, is based on Jules Michelet's 1862 book, La Sorciere (The Sorceress), better known today as Satanism and Witchcraft.

Michelet, a 19th century French social historian, was a prolific writer and an uncompromising iconoclast. He flew in the face of the then-conventional wisdom, interpreting medieval devil worship not as blasphemy, but as the reaction of natural men with natural human appetites to the politically oppressive and sexually repressive control of the Christian church.

Director Yamamoto's 1973 feature brings a modern Eastern perspective to Michelet, personifying the Frenchman's ideas in the story of Jean (voice of Katsutaka Ito) and Jeanne (Aiko Nagayama), an attractive peasant couple who seek the permission of their local lord (Masaya Takahashi) to marry.

Jeanne, unfortunately, is a bit too attractive.

The lord demands his droit du seigneur. Jeanne, whose beauty offends the lord's mistress (Shigako Shimegi), is passed about among the knights and retainers, an injustice that introduces her to unbridled lust and opens her to the influence of the Devil (Tatsuya Nakadai).

She thus begins a lifetime of torment that will see her achieve success as a money lender, be hounded as an outcast, and finally wed herself to Satan and gain followers through the healing power of her herbs and her organization of life-affirming orgies.

Such a nutshell synopsis only begins to describe the multiplicity of moods, styles and influences that Yamamoto uses to bring his story alive. His film, an incredible visual experience, is a graphic arts compendium that incorporates traditions from medieval Japanese scrollwork to trendy TV advertising art.

With a kind of mad eclecticism, Yamamoto leaps from style to style to affirm the immediate mood of a scene. When, for example, Jeanne finally gives in, body and soul, to the power of Satan, she is rewarded with a vision of his future triumphs, represented by an explosion of 20th-century images in the style of Peter Max by way of director George Dunning's Yellow Submarine (1968).

At another point, Jeanne's world falls victim to the plague. Here, Yamamoto hearkens back to some of the more frightening moments from Fantasia's "Night on Bald Mountain" sequence. (Even Disney, it will be remembered, let his animators depict comely nude wenches dancing in the fires of hell.)

Providing a magnificent aural continuity is a hauntingly appropriate musical score. Written by Japan's best-known film composer, Masahiko Sato — he created memorable themes for such Kurosawa epics as Yojimbo (1961) and Sanjuro (1962) — it eases the way for Yamamoto's sudden shifts of tone and texture.

Indeed, virtually the only harsh thing that can be said about Belladonna is that it lacks the rapid pacing that audiences have come to expect from cartoons. In contrast to contemporary American animator Ralph Bakshi, who injects a manic drive even into his most thoughtful films, Yamamoto unrolls his scrolls with contemplative, unhurried concentration.

Unhurried as it is, though, Belladonna is worth contemplating. Moviegoers who enjoyed last year's Fantastic Planet should find the current film equally rewarding.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1976. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Animation is as close as the motion picture medium comes to pure imagination. If Walt Disney deserves the credit for recognizing that such films could be more than cartoon comedies —1940's Fantasia remains a cinematic landmark — his studio also deserves the blame for settling into a musical-fantasy formula that froze such features into an entertainment aimed at children until the late 1960s. In past postings, I've noted the importance of Fritz the Cat creator Ralph Bakshi to the explosion of adult animation in the U.S. It's worth remembering, though, that Bakshi was part of an international blossoming of feature animation that involved cartoon creators in Canada, the U.K., Europe and Japan. Osamu Tezuka, the artist considered by many film historians to be the Asian Walt Disney, was already famous in Japan for his manga (comic books) when he joined with writer/director Eiichi Yamamoto in 1961 to found Mushi Production. Before going bankrupt in 1973, the pioneering anime studio challenged audiences with its Animerama trilogy: A Thousand and One Nights (1969); Cleopatra (1970; released in the U.S. as Cleopatra: Queen of Sex); and Belladonna (1973). Today, the idea of adult animation is often reduced to an obsession with sex. In fact, the excitement for sophisticated filmgoers came from seeing cartoonists claim the right to use their art to examine social, political, economic, cultural and religious issues, material not touched upon in the family-friendly worldview of the Disney cartoons.

A new age of animation dawned in 1995 with the release of Toy Story, the first animated feature entirely the work of CGI (computer-generated imagery) artists. In 2002, AMPAS, the Hollywood industry's chamber of commerce, acknowledged the the importance of the new technology by creating an Academy Award for "best animated film." To date, 14 of the new Oscars have been given out (all listed below). With one exception — Hayao Miyazaki's 2002 feature Spirited Away — each winner has been the sort of cartoon fantasy that generates a major toy merchandising campaign. Not a big surprise when you consider that 10 of the 14 were released in the U.S. and Canada by the Disney corporation. Nor were the animators out to push any real boundaries. Five of the 14 features received G (for General) entertainment ratings from the MPAA, with the remaining nine earning the mild PG (for Parental Guidance) label. So far, the new age has offered some genuinely entertaining movies, but little to challenge mature minds.

Animated feature Oscar winners listed with production company, distributor and rating noted — Shrek (2001; Pacific Data/DreamWorks; PG); Spirited Away (2002; Studio Ghibli/Disney; PG); Finding Nemo (2003; Pixar/Disney; G); The Incredibles (2004; Pixar/Disney; PG); Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit (2005; Aardman/DreamWorks; G); Happy Feet (2006; Roadshow/Warner Bros; PG); Ratatouille (2007; Pixar/Disney; G); WALL-E (2008; Pixar/Disney; G); Up (2010; Pixar/Disney; PG); Toy Story 3 (2011; Pixar/Disney; G); Rango (2012; Nickleodeon/Paramount; PG); Brave (2013; Pixar/Disney; PG); Frozen (2014; Disney; PG); Big Hero 6 (2015; Disney; PG);