Friday, June 13, 1986.

FIRE AND ICE. Written by Roy Thomas and Gerry Conway. Based on characters created by Frank Frazetta and Ralph Bakshi. Music by William Kraft. Co-produced and directed by Ralph Bakshi. Running time: 81 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: frequent violence.

THEIR COMPANY IS CALLED Ralph Bakshi-Frank Frazetta Productions. Goodness knows, they were made for each other.

Frazetta, a former comic book artist, is currently [1986] America's best-known fantasy illustrator. His incredibly muscular warriors and their impossibly voluptuous women have sold millions of posters and paperback novels.

Bakshi, the former Terrytoons cartoon director, is currently the film industry's most notorious maker of animated features. No Disney clone, he made his name with the X-rated Fritz the Cat (1972), and had the courage to take on the task of animating J.R.R. Tolkien's fantasy epic, The Lord of the Rings (1978).

Together, Bakshi and Frazetta are responsible for Fire and Ice, an attempt to bring Frazetta's particular kind of heroic fantasy to life on the big screen. Originally released in 1983, the cartoon feature has taken nearly three years to find its way into a Vancouver theatre.

Its story — devised by the producers, but turned into a screenplay by comic book professionals Ray (Conan) Thomas and Garry (Firestorm) Conway — is set in a primeval world of loinclothed swordsmen and breathtakingly busty women.

It introduces us to the white-haired sorcerer Nekron (voice of Stephen Mendel), a nasty young man who psychically controls the forward momentum of a huge glacier. Nekron is using his glacier — the "ice'' of the title — and an army of shambling subhumans to move against Fire Keep, the stronghold of good King Jarol.

We see them roll over a village, then meet Larn (William Ostrander), a Nordic-looking hero who narrowly escapes death at the beastmen's hands.

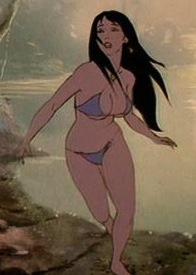

Meanwhile, at Fire Keep, agents of Nekron's scheming mother, Queen Juliana (Susan Tyrrell), kidnap pouty, raven-haired Princess Teegra (Maggie Roswell). Like Larn, with whom she'll make common cause later in the story, Teegra is able to escape her captors, but at the cost of most of her costume.

As befits a Frazetta maiden, Teegra plays out her role clad only in a G-string and a virtually non-existent halter top. Art buffs will note that Bakshi's animators lavish their most loving attention on scenes involving Teegra's heaving bosom (although the death throes of mortally wounded subhumans rate a close second).

As in The Lord of the Rings, Bakshi's art department makes extensive use of rotoscoping (the process of tracing the animation cels to match previously filmed live-action footage), and there are moments when the indifferent acting shows through. Although it accelerates the production process, the reliance on rotoscoping can limit an animator's imagination.

Overall, though, Bakshi benefits from having a consistent style — that's Frazetta's contribution — to govern the look of his picture. Though Fire and Ice lacks the soaring imagination of his masterpiece, 1973's Heavy Traffic, it is actually his best realized picture to date.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1986. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Brooklyn-born Frank Frazetta was 10 years older than fellow Brooklynite Ralph Bakshi, which meant that he came of age in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War. A talented artist, he acknowledged a stylistic debt to Canadian-born Hal Foster, creator of the classic Tarzan and Prince Valiant comic strips. Frazetta's own career began in New York's comic book studios and progressed into newspaper comic strips. In the mid-1960s, he broke though into more remunerative commercial art markets, creating dynamic posters for Hollywood movies — more than a dozen titles, from the Peter Sellers comedy What's New Pussycat (1965) to the Clint Eastwood thriller The Gauntlet (1977) — and covers for paperback novels. According to the New York Times, Frazetta's distinctive style defined "fantasy heroes like Conan, Tarzan and John Carter of Mars" as well as "creating a new look for fantasy adventure novels that established [him] as an artist who could sell books." His images caught the zeitgeist of that revolutionary moment when the baby boomers embraced the popular culture, and director John Milius has said that his goal, in adapting Conan the Barbarian into a 1982 Arnold Schwarzenegger movie, was to tell a story shaped by Frazetta and composer Richard Wagner.

A pioneer of the creator's rights movement, Frazetta was one of the first artists to negotiate the ownership of his artwork. His foresight was rewarded in 2009, when his cover painting for the 1966 Lancer books edition of Conan the Conqueror sold at auction, earning the artist $1 million. At the height of his popularity, Frazetta joined with his long-time friend Ralph Bakshi to produce the animated feature Fire and Ice. In their 2008 book Unfiltered, Bakshi biographers Jon Gibson and Chris McDonnell report that "Ralph and Frazetta never strayed far from one another. The duo reveled in every bit of the process, from casting sessions with voluptuous vixens to the live-action antics on a soundstage in Hollywood . . . [they] were laughing their asses off the entire time." Among the players in the movie filmed as a guide for the animators was Frazetta's adult daughter Holly (playing the Subhuman Princess). In 2010, the year Frazetta died, Holly entered into a deal with director Robert Rodriguez, who then announced his plan to produce a live-action remake of the animated feature. The picture is currently "in development" with no filming date set.

See also: For more on the life and work of adult animation pioneer Ralph Bakshi, check out my 1978 interview with him. The Reeling Back archive also contains reviews of most of his films, including Fritz the Cat (1972); Heavy Traffic (1974); Wizards (1977); The Lord of the Rings (1978); American Pop (1981) and Cool World (1992).