Wednesday, November 8,1978.

RALPH BAKSHI PROFILE

By Michael Walsh

By Michael Walsh

STUDIO PUBLICISTS CALL HIM a revolutionary. The critics say that he's a gambler.

"I'm a cartoonist," shrugs Ralph Bakshi, director of an $8-million animated adaptation of The Lord of the Rings. "I don't see myself as a revolutionary, and making a movie is much more of a producer's gamble."

Once a boxer, Bakshi leans into hls words, as if each thought must be seized physically. "Actually, I'm a film director who happened to start out as a cartoonist. I'm probably a better film director."

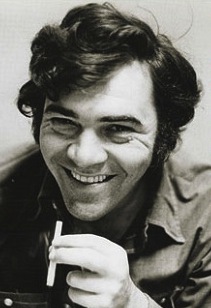

A big man with a slight lisp, he looks less like an artist than a bartender, an image reinforced by his easy grin and Brooklyn accent. Conversation is casual, confidential and just a little intimidating. Dressed in blue jeans and a work shirt, Bakshi maintains an air of aggressive modesty.

The publicists are right, of course. He is a revolutionary. Almost single-handedly, he has transformed animation into an adult art form. Remember Fritz the Cat?

Billed as the first "X-rated cartoon," Fritz was also Bakshi's first feature. Based on a character created by underground comic artist Robert Crumb, it offered movie audiences a new kind of theatre experience.

Fritz was petty, profane, crafty and craven, a character completely concerned with sex. Like Mickey Mouse, he walked upright, wore clothes and lived in a world of anthropomorphic animals. Unlike Mickey, Fritz was twice banned in B.C.

Made in 1971, Fritz the Cat did not make it past the provincial classifier until 1973. Once in, though, he was given a gala reception at the Varsity Theatre's annual Festival of International Films. When the fllm later opened on Theatre Row, Vancouver's large community of cartoon fanciers turned out in force, guaranteeing Fritz a long and prosperous run.

The 1950s and 1960s were hard times for animation buffs. From its beginnings, television demanded that cartoons be made both fast and on the cheap. A pair of former M.G.M. cartoonists, Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera, stooped to the challenge, providing formula product for the tube. They perfected the technique of "limited animation," the mechanical process that has turned the Saturday morning schedule in the U.S. into a mindless wasteland.

Hanna-Barbera became a major production company. Eventually, they had sub-contractors all around the world — a group of companies that once included Vancouver's Canawest Films. Its methods and style became standard for the industry: junk programming to sell junk food.

Is it any wonder that Fritz succeeded? Bakshi was a rebel against artless animation. His picture, two years in the making, represented a return to the days of inspiration, imagination and artistic integrity.

"I'm a cartoonist. I love Walt Disney." But, says Bakshi, "I don't want to be Walt Disney. What I want to do is take an art form that has become bastardized and make it legitimate for adults.

"The whole point of my life has been my dedication to animation. Before that" he adds, grinning, "it was my dedication to hanging out."

Ralph Bakshi hung out in Brooklyn's Brownsville district, a working class, Jewish neighbourhood once described as "a nursery of tough guys." Bakshl grew up trying to be a tough guy.

"It was the usual bullshit," he says. "Guys, gangs, basketball, broads. I was playing the part with my blackjack and things, and whatever the guys were doing, I was doing." Told by his high school principal that he was a nothing, a hoodlum who would never amount to anything, Bakshi transferred to a vocational school.

"You could spend three years drawing all day. You could sit there, do zero, get your diploma and split. You were allowed to take as many art courses as you wanted, and for every art course you took, you had to drop an academic course. So, I dropped all my academic courses and took art all day."

Bakshi graduated from the School of Industrial Art in June, 1956. In November, he went to work for Terrytoons, an animation studio that had recently been acquired by CBS television. That same year, he first read The Lord of the Rings.

A malaise had settled over the cartoon business, making it easy for an ambitious young man to rise quickly. By 1966, Bakshl was supervising director at Terrytoons. Eight months later, he quit. "Basically, I had a ten-year apprenticeship," he says.

Moving over to the Paramount Pictures cartoon studio, he became director of production. He was 26. The job lasted less than a year. Shortly after Bakshi joined the company, corporate raider Charles Bluhdorn was installed as president of Paramount, and the cartoon studios were closed.

Bakshi didn't stay unemployed for long. He was soon running a cartoon shop for an equally ambitious TV producer named Steve Krantz, an association that would ultimately give birth to Fritz the Cat.

Not everyone liked Bakshi's Fritz. Among those who were not amused was the cat's creator, Robert Crumb. "I didn't like the sex attitude in it very much," Crumb said after seeing the film. "It's, like, real repressed horniness, He's kind of letting it out compulsively."

Crumb was probably right. If so, though, it was the first time that a cartoonist had ever produced a truly personal feature. And that, even more than the language or situations, was a first for American animation.

The critics are right about Bakshi, too. He is a gambler. His second feature, 1973's Heavy Traffic,

Bakshi turned the project into a brilliant, blistering, occasionaly brutal bit of autobiography. According to Variety reviewer Robert Frederick, the picture had "something to offend everyone." Perhaps. Perhaps Frederick, a Variety senior staffer and a man nearing retirement age, had expected to see a children's film.

What he and the public got was a look into Bakshi's soul. The film's outrages were exorcisms, as the filmmaker told the story of Mike, a would-be artist, trapped in a world of tenements, barrooms, gangsters and grotesques.

Bakshi is too honest to lie about it. The Lord of the Rings may he his current film, his biggest film and his most important film. But, he admits, Heavy Traffic remains his favourite film.

Not all of his efforts have been well received. Coonskln (1975), a biting parody of Disney's tuneful Song of the South, incurred the wrath of black community leaders and was withdrawn. Hey Good Lookin' , nostalgia for the streets of Brooklyn circa 1955, has never been released.

Bakshi realized that if he was to make the kind of movies he wanted to make — "There's no way I can't continue to be me" — he would need some real clout at the box office. For that, he needed a blockbuster, a Godfather,

But first came Wizards, released in 1977 and a surprise hit. Relatively tame in both tone and technique, the film was raggedly plotted and lacked a consistent visual style. Indeed, it looked more like a series of tests for the major film that Bakshi was finally able to put into production.

It took two and a half years, a rush job by Disney standards but unbearably long in a world dominated by Hanna-Barberians. He completed the picture on Sunday, October 29, 1979, then settled back in a state of mild shock. It was Bakshi's 40th birthday.

He shakes his head, retreating a little, dropping his guard for a moment. The grin disappears. "I became 40," he says, the words coming more slowly.

"I didn't throw a party. I don't know what's happening, or how I really feel about it. There's . . . confusion. I guess I'll take a week off, go home to New York for a rest and have some fun."

What does Ralph Bakshl do for fun? "I dunno. That's one of the things I'm going to have to find out about."

The Lord of the Rings, currently [1978] on view in Vancouver, tells approximately half of Tolkien's story. It ends with the battle of Helm's Deep, an epic conflict that occurs midway through the published trilogy. If it is commercially successful, Bakshi is ready to start production on Part Two. If he wins his gamble, he will have created the biggest animated epic in film history.

If he wins, he'll have the kind of clout he's always wanted. "I don't want to do rabbits chasing mice," he says. "I want to do what live-action directors do, and do it in my own medium.

"The kind of stories I want to make have political and adventure themes. Artists should make feelings. I want to capture what you see in a Vegas casino, for example — the hunger of the people at the slot machines."

He hasn't thought much about The Lord of the Rings, Part Two. He's more concerned with the next purely Bakshi project. He has an idea for a film called American Pop.

"It's all about America from 1800 to contemporary times, about success and how making it took on such an over-riding importance in this country. It's about how some men became heroes while leaving a trail of bodies behind them all the way. The Rockefellers, the rock scene, the drug scene, Vegas — it's all in there."

Can Bakshi be serious? What does a high school drop-out from Brownsville know about success in America?

"I know about a lot of people striving for it, and to what lengths they've gone to achieve it. It's really a two-headed coin. There are great ones who make it who actually do deserve to make it."

Revolutionary. Cartoonist. Gambler. Bakshi shrugs, grins, leans closer.

"It's not a gamble. I mean, what else can I do?"

The above is a restored version of a Vancouver Magazine feature profile by Michael Walsh originally published in 1978. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Bakshi steered the conversation away from any discussion of The Lord of the Rings, Part Two. He probably already knew that United Artists had no intention of going forward with the project, and that his own lasting legacy would be his more personal features. American Pop

Abandoning features for television, Bakshi wrote and directed the made-for-TV movie Cool and the Crazy for Showtime in 1994. His only live-action feature, it starred Jared Leto and Alicia Silverstone as an unhappily married couple growing apart in the 1950s. In 1997, he created the single-season HBO series Spicy City, a noir-ish sci-fi show aimed at the adult animation audience that he'd been the first to identify in the 1970s. Although he retired to painting and teaching around 2000, retirement didn't really take. As I noted in the Afterword to my review of American Pop: "Currently we are awaiting the promised 2014 release of Last Days of Coney Island. The story of an NYPD detective and the prostitute that he both loves and arrests, it's the result of an online Kickstarter campaign and Bakshi's newfound romance with computer animation." As it turns out, the new movie is being released today (October 29, 2015), a gift from Bakshi to his legion of fans on the occasion of his 77th birthday. The 22-minute cartoon is available on Vimeo, the video-sharing website. Yesterday, the gothamist.com website posted a new interview with Bakshi

See also: The Reeling Back archive also contains reviews of most of Ralph Bakshi's films, including Fritz the Cat (1972); Heavy Traffic (1974); Wizards (1977); The Lord of the Rings (1978); American Pop (1981) Fire and Ice (1983) and Cool World (1992).