Thursday, February 23, 1978.

THE BETSY. Written by Walter Bernstein and William Bast. Music by John Barry. Directed by Daniel Petrie. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: occasional sex.

LEWIS GILBERT HAD NO CLASS. In The Adventurers, his 1970 film based on the Harold Robbins novel, he had his opportunistic hero (Bekim Fehmiu) relieve the heiress-heroine (Candice Bergen) of her virginity in a greenhouse.

Outside, on her family’s estate, a celebration was going on. At the moment of consummation director Gilbert cut to a fireworks display.

Daniel Petrie has class. In The Betsy, his current film based on yet another Robbins novel, he has his opportunistic hero (Tommy Lee Jones) relieve the heiress-heroine (Kathleen Beller) of her virginity in a guesthouse.

Outside, on her family’s estate, a celebration is going on. Director Petrie shows his class by leaving out the gratuitous fireworks.

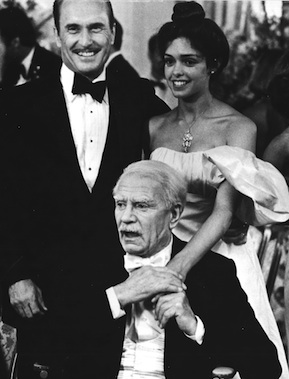

The girl in the guesthouse is Elizabeth “Betsy” Hardeman, played by Beller with a softness and vulnerability usually missing from the sock-it-to-me Robbins woman. She is the great-granddaughter of Loren Hardeman (Laurence Olivier), founding father of Bethlehem Motors and a man with a better idea.

Hardeman is nearly 90 and, although he is no longer in control of his own company, he is determined to build himself a motorized monument. Like Henry Ford and Adolf Hitler, Hardeman wants to give the world a “people’s car,” a revolutionary, inexpensive vehicle that will give owners 60 miles per gallon.

He plans to call it The Betsy.

To get the job done, he recruits an auto-racing champion named Angelo Perino (Jones), a driver who also happens to be a top-notch engineer. Together they plot to thwart Bethlehem’s dollar-conscious president, Loren Hardeman III (Robert Duvall).

In its advertisements, Allied Artists is pushing the idea of “. . . the Harold Robbins people. What you dream . . . they do!”

In the movies, they usually do it with listless boredom. The Robbins people seldom make sympathetic characters.

It’s here that Petrie and The Betsy score. Though Betsy Hardeman is sure that the auto magnates are “all monsters,” Petrie’s casting and direction manage to turn them into interesting, cheerfully cuddly monsters.

At the centre of it all is Olivier. As Hardeman “Number One,” he ages through about 45 years, and proves to be a most lovable monster. Instead of the swashbuckling captain of industry envisioned by Robbins, Olivier plays the role as if he were parodying Hans Conried. His Hardeman is a squeaky-voiced old curmudgeon who seems slightly detached from reality.

It’s hard to take him, or his roundheeled great-granddaughter, seriously. For its first hour, Petrie’s film seems ingenuously inept, as if the director were actually satirizing his Robbins people.

Midway through, there is a boardroom battle to decide the fate of The Betsy. Suddenly, the mood of the movie shifts, and we realize that Petrie himself has pulled off a minor coup.

His gently comedic first half has managed to introduce a small army of characters and several subplots without confusion or heavy melodramatics.

Robbins, as everybody knows, plots as if it’s going out of style. His perennial best-seller status comes from the fact that he knows how to tell one hell of a story. In the second half, when Petrie begins to draw all his plot strands together, it becomes obvious that this movie contains no throwaway material at all.

As in a carefully constructed car, every nut, bolt and screw is a deliberate part of the design. Throughout, Petrie’s touch remains light, tight and bright.

The Betsy is a pulp-fiction fantasy that combines excitement with a sense of fun.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1978. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: In a 1977 interview, Kathleen Beller said that getting the title role in The Betsy “was actually the easiest part I ever got.” A director familiar with television drama, Daniel Petrie decided over a lunch meeting that the TV actress would make her feature film debut in the starring role. Petrie cast Beller again in his powerful urban drama Fort Apache, the Bronx (1981), where she had a supporting role as young cop Ken Wahl’s fiancee. That same year, Beller starred in Canadian director Claude Jutra’s adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s novel Surfacing, the story of a young woman’s search for her missing father. Thereafter, she had the bad luck to be cast in such unappealing screen fare as The Sword and the Sorcerer (1982). Remembered best for her television work, including her two seasons as a regular on the prime time soap opera Dynasty (1982-1984), Kathleen Beller married musician Thomas Dolby in 1988. She made her last film appearance four years later, a cameo role in the 1992 independent feature Life After Sex.

Sex, of course, was author Harold Robbins’s stock-in-trade. Once the most popular writer in the world, he ground out works “of no particular literary distinction” (according to Richard Schickel), publishing 23 novels prior to his death in 1997 (with another 12 published posthumously). Although he began writing in 1946, he kept his day job (a budget and planning director with Universal Pictures) until 1957. Between 1958 and 1983, a dozen of his best-sellers were made into feature films or TV movies, including Never Love a Stranger (1958); King Creole (based on A Stone for Danny Fisher; 1958); The Carpetbaggers (1964); Where Love Has Gone (1964); Stiletto (1969); The Adventurers (1970); The Pirate (TV, 1974); 79 Park Avenue (TV, 1977); The Betsy (1978); The Dream Merchants (TV, 1980); and The Lonely Lady (1983).

In an email interview with the American Legends website, Betsy screenwriter William Bast is quoted as saying “Harold Robbins told me that he considered The Betsy the ‘best movie adaptation of any of his works’.” It remains a curious fact that three of the nine Robbins big screen adaptations were the work of directors from Canadian small towns. Both The Carpetbaggers and Where Love Has Gone are among the credits of Edward Dmytryk, whose roots were in Grand Forks, British Columbia. The Betsy director Daniel Petrie was born in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia.

See also: Daniel Petrie discussed making the The Betsy in an interview during a 1978 visit to Vancouver to promote the film’s release.