Thursday, February 6, 1986.

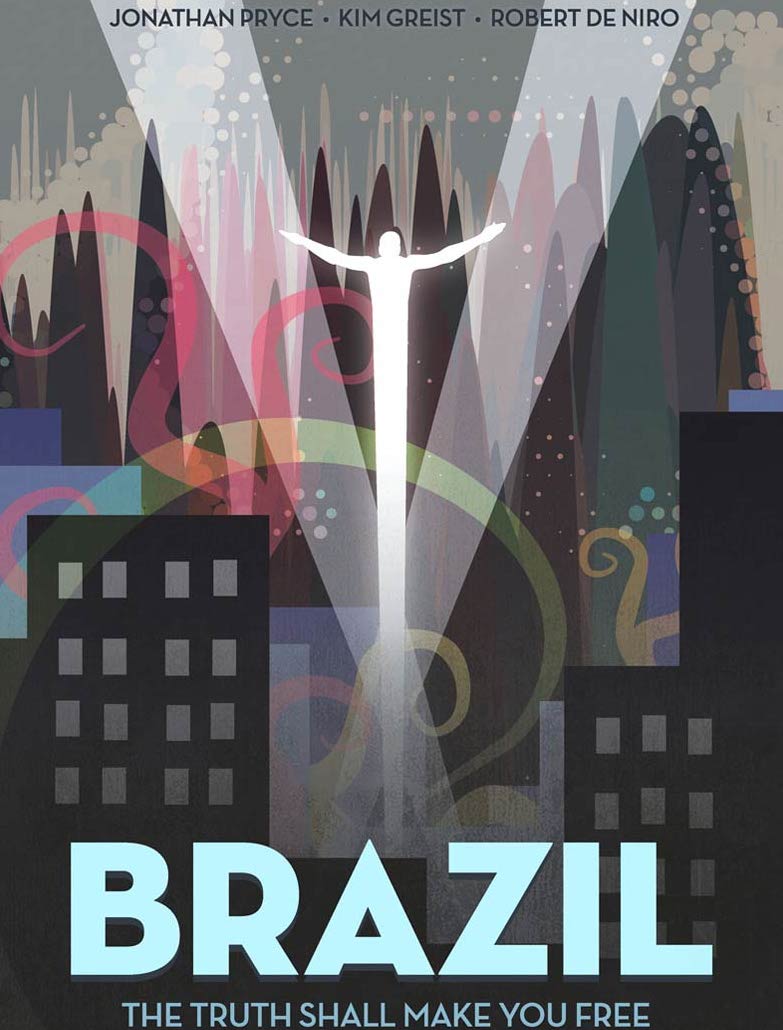

BRAZIL. Co-written by Tom Stoppard and Charles McKeon. Music by Michael Kamen. Co-written and directed by Terry Gilliam. Running time: 132 minutes. Rated Mature with the B.C. Classifier’s warning "occasional gory scenes, very coarse language and swearing."

BRASIL.

The tune kept running though Terry Gilliam’s head. Da-da! Dah-da-dahdah-dah! Dah-daaah!

“There’s something about it that’s so silly and at the same time so pathetic,” the Monty Python alumnus said in a recent interview. “ . . . a desperate bid to escape against all the bravura of samba music.”

Originally written in 1939, composer Ary Barroso’s rhythmic evocation of faraway Rio has been used in half a dozen Hollywood musicals. “It’s triggered off a lot in me,” says Gilliam, director of the first film actually inspired by it.

Brazil. During production it was referred to as “1984 ¼.” Written with Tom Stoppard and Charles McKeon, it is Gilliam’s “post-Orwellian view of a pre-Orwellian society.”

Filmgoers who delighted in the director’s two previous departures from the classics — Jabberwocky (1977), a brilliantly idiosyncratic medieval comedy “suggested” by Lewis Carroll’s poem, and Time Bandits (1981), a deliciously original contemplation of good and evil in the manner of C.S. Lewis — have awaited his musing on Orwell with eager anticipation.

Brazil, completed in 1984, sat on its American distributor’s shelf. The picture was “interminable” and “unreleasable,” MCA president Sid Sheinberg told the Los Angeles Times.

Gilliam fought back. In its annual year-end balloting, the L.A. Film Critics Association voted its best picture, director and screenplay awards to the feature Universal Pictures had deemed too highbrow and inaccessible for the American audience.

Brazil, now in release, is great. An impassioned, tragi-comic look at life, liberty and the omnipresence of ductwork, it is a masterpiece of literate whimsy, the work of an instinctive satiric genius.

Set “somewhere in the 20th century,” it is the story of Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce), a cheerfully unambitious bureaucrat who occasionally dreams about Icarus-like flights above his nation’s blighted landscape. In such moments of narcoleptic reverie, he is on a quest to free a mysterious maiden in a diaphanous white gown.

One day, he sees his dream girl in the city. She is Jill Layton (Kim Greist), a truck driver and (he believes) a member of an underground terrorist movement. Knowing that she exists in the flesh changes his life, as the once-content Lowry becomes eager to gain the promotions necessary to give him the authority to track her down so that he can win her heart.

No simple action-adventure story, Brazil creates its own shrewdly anarchic version of an Orwellian future, the sort of fully-formed, keenly-observed comic vision that one expects of a charter Pythonite.

“I want to talk to you about ducts,” intones a government spokesman.

Why a duct?

Why not? Like his contemporary Joe (Gremlins) Dante, Gilliam recognizes that cinema is the collective unconscious of modern man, a universe of symbols and images that shapes our response to the waking world.

Unlike Dante, whose pictures seem to exist for the sake of their clever movie quotes, Gilliam creates a chillingly real comic environment that evolves naturally from its pop-culture referents. Brazil’s black humour is actually multi-hued, a dazzling performance from which Gilliam emerges as the James Joyce of filmdom.

Far better than any of the official Oscar nominees, his picture is as immediate as the latest headline outrage, a tapestry of images and ideas that haunt the mind like the lyrics of its title tune.

There’s one thing I’m sure of . . . Return I will to old Brasil.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1986. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: The 1985 Academy Award best picture nominees were director Steven Spielberg’s The Color Purple, Héctor Babenco’s The Kiss of the Spider Woman (which, as it happens, is set in Brazil), Sidney Pollack’s Out of Africa, John Huston’s Prizzi’s Honor and Peter Weir’s Witness. On March 24, 1986, the best picture Oscar went to Out of Africa.

Before it was a country, Brazil was an idea. In pre-Christian Irish mythology, Brasil (or Hi-Brasil), was an island that existed somewhere in the western sea. Like Scotland’s Brigadoon, it was a phantom place, shrouded in mist for but one day every seven years. (Nineteen eighty-nine appears to have been one of those years. Hy-Brasil is seen in Erik the Viking, a comic fantasy directed by Terry Gilliam’s Monty Python colleague Terry Jones.) Inaccessible to all but the greatest heroes, the island represented a kind of paradise, a place described in a seventh-century myth as a land of eternal happiness without sickness or strife where music is always to be heard.

The country called Brazil was claimed for the Portuguese crown in April, 1500, by the explorer Pedro Álvares Cabral. Today (October 28), voters in the largest nation in South America face a choice between the populist Jair Bolsonaro (described on the cover of the September 20, 2018 Economist as “Latin America’s latest menace”) and Fernando Haddad, the designated successor to the popular Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who is serving a prison sentence for corruption. The results of the run-off election will be felt around the world for years to come.

The movie called Brazil is, of course, a combination of myth and political reality. Bringing together the Shakespearian genius of playwright Tom Stoppard with the cinematic wit of Terry Gilliam, it remains a pertinent social satire.

See also: Other Terry Gilliam works included in the Reeling Back archive are 1981’s Time Bandits and Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life (1983). Tom Stoppard’s Shakespearean genius is on display in the writer-director’s screen adaptation of his stage play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1990).