Friday, November 17, 1967

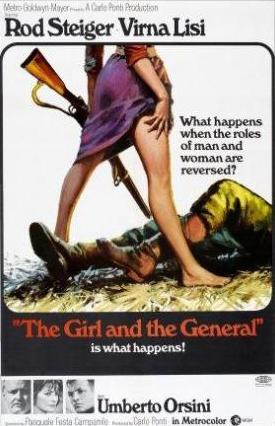

THE GIRL AND THE GENERAL (La ragazza e il generale). Co-written by Luigi Malebra. Music by Ennio Morricone. Co-written and directed by Pasquale Festa Campanile. Running time: 103 minutes.

WHEN CHICAGO PROFESSOR MORTIMER Adler set out to cross-index the world’s "Great Books,” he included among his 102 key concepts the idea of war. Recently, though, many filmmakers have come to the conclusion that war isn’t such a “Great Idea" after all.

The latest blast from the war-is-bad-wagon to reach Toronto is The Girl and the General, an uninspired collection of the most trite and tiresome anti-bellum blather.

Girl, a Carlo Ponti export, concerns itself with the First World War conflict between Austria and Italy. Umberto Orsini is cast as Tarasconi, an inept, illiterate Italian private soldier who oversleeps his army’s retreat and inadvertently captures an enemy general, played by Rod Steiger.

Tempted by the hope of a medal and a handsome reward, simple-minded Tarasconi determines to escort his prisoner back to Italy from behind the advancing Austrian lines. He is both helped and hindered in his task by Ada (Virna Lisi), a strong-willed peasant girl who joins them along the way.

Few would argue with its basically humane premise. But Girl, in an attempt to make its point of view more potent, stoops to stereotypes.

Tarasconi, freckle-faced and with a mouth as jagged as a bayonet slash, is the immortal enlisted man. For three hungry, tiring years he has festered in the blood-soaked mud of a conflict he can neither understand nor change.

The General, stocky and bespectacled, is a proud, patrician officer for whom the military is a family tradition. He demands treatment in accordance with the Geneva Convention, the “rules” of the “game” that he so complacently plays.

Ada, smooth-skinned and shapely, represents long-suffering humanity, a civilian population caught up in the ebb and flow of battle. She has become hardened to all sides, and contents herself with mere survival.

The film would have been more interesting if any of its stars managed to bring the slightest bit of believability to their parts. Orsini and Lisi, unfortunately, are hopeless muggers throughout.

Steiger, in common with so many American stars who sell their names to foreign producers, couldn't have cared less. His brand of militarism seems no more menacing than that of Lord Baden-Powell’s Boy Scouts.

The trio’s rural trek suffers more annoyance from the movie’s inane, inappropriate musical score than from the spike-helmeted Austrians. Its Silly Symphony tones would have been more appropriate to a cat-and-mouse cartoon.

The film’s single greatest weakness, though, is its banal script. Co-written by director Pasquale Festa Campanile, it fills the characters’ mouths with well-worn cliches.

“Hey,” Tarasconi says, “how come you never see no dead generals?”

“There are more privates,” the General sneers back.

At times the truisms fly so thick and fast that it’s impossible to count them. The General describes the Geneva Convention as “a gentlemen's agreement.”

"If the world were made of gentlemen,” Tarasconi thoughtfully points out, "there'd be no wars.”

It seems so very right that Tarasconi and Ada find love, and each other, one night in a bomb crater by the shimmering light of the artillery salvoes.

Several weeks ago [in 1967], actor-director Cornell Wilde’s Beach Red arrived in town with a similar anti-war agenda. A more eloquent, powerful and convincing feature, it played an unjustly short run at a number of Odeon’s neighbourhood cinemas.

The Girl and the General, a hollow pretence of meaningfulness, is inexplicably showing at the theatre chain’s downtown [Toronto] flagship, the Carlton.

The above is a restored version of a Toronto Telegram review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1967. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Among the many memorable quotes attributed to Groucho Marx is one that goes “I don’t want to belong to any club that would have me as a member.” The contrarian in me has always said amen to that. During my college days, a time when most campuses were hotbeds of liberal-minded protest against America’s Vietnam war, I was at my most conservative. I went so far as to join the army, specifically the Canadian Officer Training Corps, a program that paid my university tuition. The experience had the unintended consequence of bringing me closer to my father, a decent but distant man who had served king and country during the Second World War. During my own enlistment, I trained at Base Borden, Ontario, where I discovered two things about myself: I was an excellent marksman and, at heart, a pacifist.

I know that the above review, trashing the Italian anti-war comedy The Girl and the General, does not read like the work of a pacifist. My problem with the picture was (and remains) that it wasn’t a good anti-war movie. I knew a good one when I saw it. The year 1964 had produced a trio of them: Canadian director Arthur Hiller’s The Americanization of Emily, Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, and Joseph Losey’s King and Country. Among the absolute best were Austrian writer-Director Bernhard Wicki’s 1959 drama Die Brücke (The Bridge) and Philippe de Broca's 1967 classic Le roi de coeur (King of Hearts). The year 1979 brought with it the most powerful plea for peace of them all, Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now.

In remembrance: Today’s additions to the Reeling Back archive include 1966’s The Blue Max, The Girl and the General (1967) and The Great Waldo Pepper (1975).