Monday, April, 24, 1972.

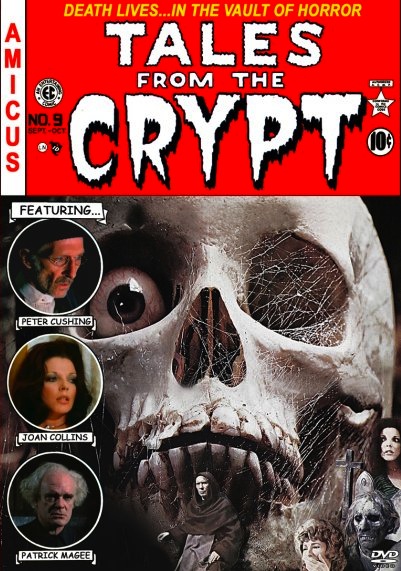

TALES FROM THE CRYPT. Written by Milton Subotsky. Based on stories from the comic magazines Tales from the Crypt and The Vault of Horror by Johnny Craig, Al Feldstein and William M. Gaines. Music by Douglas Gamly. Directed by Freddie Francis. Running time: 92 minutes.

IT ALL SEEMS QUAINT and slightly silly today, but a generation ago [1952] comic books were a serious social issue. The late 1940s saw the beginning of a great Crusade to Clean up the Comics, and in Canada the greatest centre of opposition to the dime dreadfuls was right here in British Columbia.

At issue were American-made crime and horror comics, and it began with some concerned parents looking into their children's favourite reading. What they found were worlds soaked in blood and embalming fluid, fantasies in which the crimes were bizarre, justice retributive and punishments sickeningly appropriate.

In 1948, a child was found hanged among his comics, and the books took the blame. Kamloops M.P. Davie Fulton, at the time a Conservative member of the Federal opposition, introduced a bill banning the importation and sale of all such comic magazines. From December, 1949, all Canadians were protected from such publications as EC's Tales from the Crypt.

That a current [1972] film should have the same title as a long-defunct line of comics is no coincidence. Tales from the Crypt credits EC publisher William M. Gaines and the comic's editor Albert B. Feldstein as the original creators of its material.

Gaines, after a round of 1954 testimony before a U.S. Senate committee investigating the effects of his products on children, discontinued most of his comic-book lines. The sole survivor was a satirical monthly called Mad, a publishing success that Feldstein later joined as editor.

In 1954, to avoid the sort of federal censorship passed into law in Canada, the U.S. comic-book industry adopted the self-regulatory Comics Code, and the offending crime and horror titles disappeared overnight.

In 1966, a resurgence of interest in classic comic art traditions led to the reprinting of five Tales from the Crypt stories in a paperback that was the inspiration for the new motion picture.

An anthology film, Tales features a robed Sir Ralph Richardson as the Keeper of the Crypt. Seated on a skull-backed throne, he greets the five persons who have found their way into his catacomb, causing each of them to have a vision.

The use of a framing story is a time-honoured tradition among European filmmakers, and was used to memorable effect in the 1945 British thriller Dead of Night. More recently, director Freddie Francis successfully cast Burgess Meredith as a satanic fun-fair fortune teller in a Robert Bloch-scripted anthology called Torture Garden (1967).

Tales reunites much of the Torture Garden team. Francis, an Academy Award-winning cinematographer (for 1960's Sons and Lovers) before becoming a director, has a string of well-crafted English horror films to his credit. With Tales, he adds star power to the mix.

Besides Richardson, his film features the sultry Joan Collins as a murderous wife; Richard Greene, aging nicely into a Rex Harrison lookalike, as a bankrupt businessman; Peter Cushing, one of the horror genre's superstars, as a harmless old dustman; and former Shakespearean Patrick Magee, as the leader of a rebellion in a home for the blind.

For his storyboard, he had the original EC Comics issues. Despite their often distasteful subject matter, they drew upon some of the best graphic arts talent then available.

There was, in fact, more creative energy released in a single issue of Tales than in the whole Harlequin romance series.

Given such inspiration, the film version should be far better than it is. On this project, unfortunately, Francis lacked the skills of Torture Garden writer Bloch. The Tales framing story (concocted by Milton Subotsky, the picture's producer) is no story at all.

The American originals — in their time banned in England as well as Canada — have been reset in Britain. In order to do so, though, Subotsky has tampered with the tales in all the wrong ways. The effect is to defuse much of the motivation and render the actual horrors less effective.

It also has to be said that several of the shock themes, as fresh as they were in 1952, have since become standards. Television's Night Gallery [1969-1973] often manages more impact with virtually the same stories.

The film's most remarkable failing is its visual conception. In Torture Garden, Francis varied his style from vignette to vignette, bringing appropriate lighting and camera techniques to bear on the individual stories, giving each one its own look and feeling.

This certainly was the way the comics were conceived. Separate artists, each with his own style, rendered the originals. The film, on the the other hand, offers an unimaginatively uniform look.

The parts held much promise: the long-banned Tales from the Crypt in a name-star production from the makers of the minor genre masterpiece, Torture Garden. Horror fans had every right to expect a triumph.

Instead, the result is mediocrity.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1972. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Although the word "superhero" was coined in 1908 (in a book that used it to translate Nietzsche's term ubermensche), it didn't come into popular use until the mid-1950s. The period we now know as comics' "golden age" (1938-1955) was populated by costumed crime-fighters, such as the Bat-Man, Superman and Captain Marvel. It was only during the controversy over crime and horror comics that the embattled publishers adopted the term "superhero" to describe their creations. In the fight to prevent state censorship and protect their established character-based franchises, the publishers realized that crime (in a title) no longer paid. As a result a new genre, superhero comics, was born.

At the heart of the 1950s Crusade to Clean up the Comics was the belief that comics were, and always would be, for kids. What the concerned parents and opportunistic politicians of the day failed to realize was that the comic book was an artistic medium struggling to grow up. EC Comics, experimenting with more adult themes, were at the forefront of that evolution, a fact that is now recognized by graphic arts historians. The 1972 Tales from the Crypt feature film was part of the rediscovery. In 1979, specialty publisher Russ Cochran started an ambitious reprinting of The Complete EC Library with a five-volume, hardbound and slip-cased edition of The Complete Tales from the Crypt. Ten years later, a seven-season, 93-episode Tales from the Crypt TV series aired on HBO (1989-1996). It was the work of a team of high-powered Hollywood artists that included Superman director Richard Donner, Alien producer David Giler, Aliens executive producer Walter Hill, Die Hard producer Joel Silver and Back to the Future writer-director Robert Zemeckis.

Today, we understand that the real issue was one of fundamental rights. Davie Fulton's 1949 Bill 10 was an attack on freedom of expression that played upon a generation's concern for the safety of its children. And here we are again, listening to opportunistic politicians arguing the need for increased "security" in the debate over Canada's Bill C-51, the so-called Anti-terrorism Act, 2015. Currently (February 26) in committee, this odious document is within days of being passed into law. Among the arguments made by C-51 supporters is that it will give authorities the tools to prevent radicalized youth from leaving the country to join "terrorist" organizations. So, you see, it's all about the safety of our children. Again.