Thursday, September 30, 1982.

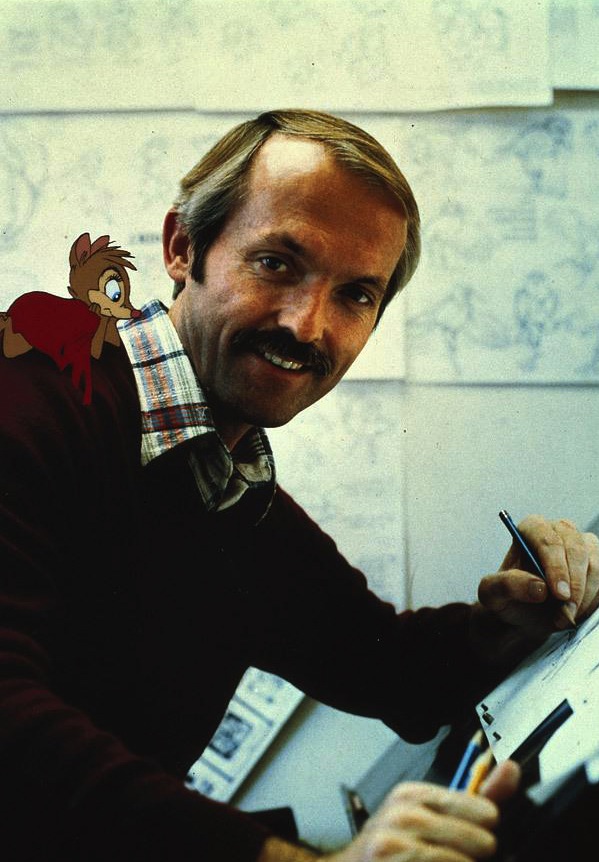

NOTHING QUITE LIKE IT HAD ever happened before. On the morning of September 13, 1979, animators Don Bluth, Gary Goldman and John Pomeroy quit their jobs at Walt Disney Productions.

The next day, ten more people resigned. Although Disney spokesmen tried to minimize the significance of their departure, it was clear that there were serious morale problems in the Mouse Factory.

"It was a dream that burst," says Bluth, the Texas-born artist who led the exodus on his 42nd birthday. During eight years at the Disney studio "I'd never seen a group of people so unhappy, and so unwilling to admit it."

Bluth, a member of the competition jury at this year's [1982] Vancouver International Film Festival for Children and Young People, had dreamed the Disney dream. "I loved the product that was once made there," he said in an interview.

"I thought if I could only work there, I could make all the beautiful things come back again."

When Bluth first went to work for Disney, his commitment to his art was total. It was 1955. Walt Disney was still alive and Bluth was an assistant animator contributing to the studio's most ambitious cartoon feature, Sleeping Beauty [1959].

Two years later, Bluth left. A practicing Mormon, he had to fulfill his missionary obligation to his church. Thereafter, he completed college and spent some time managing a theatre in Culver City, California.

In 1971, after nearly four years in the Filmation cartoon shop, he rejoined Disney. Walt was gone and animation at his studio "had turned into a very mechanical system."

Bluth, on the other hand, was no less dedicated to his craft. His talent won him regular promotions, increased responsibility and larger screen credits.

On 1977's Pete's Dragon, a live-action musical in which stars Mickey Rooney and Helen Reddy interact with a cartoon dragon, he was director of animation.

In 1979, the Disney studio introduced its "new generation" animation team to the world via a Christmas short called The Small One, produced and directed by Don Bluth. The new generation's first feature was to have been 1981's The Fox and the Hound, again with Bluth in the director's chair.

As it turned out, the new generation responsible for The Small One left to become the core of Don Bluth Productions. The company, born in Bluth's garage, quickly distinguished itself by contributing two minutes of delightful animation to the otherwise undistinguished Universal musical, Xanadu.

When Bluth talks about animation, his eyes glow with childlike wonder. "You can't do it eight hours a day and then go home," he said. "You have to be fantastically in love with it."

For seven years prior to the great defection, Bluth and his colleagues had met in the garage on evenings and weekends to hone their craft beyond the requirements of the job. "When animation becomes involved in corporations, it ceases to be an art form," he told me.

There was a time for Disney, the man, as well as for Bill Hanna and for Joe Barbera, when "the freshness and light of discovery was there," when they went home at night "and your eyes won't close because there are just too many ideas.

"lt's then that the work transcends the paint and the panels," Bluth said "That's how you make a Snow White, a Bambi or a Bugs Bunny. When you start worrying about the stockholders, well, amen to your art."

As charming and persuasive as Bluth is, the question that remained was: could he deliver? Rich Irvine and Jim Stewart thought he could.

A pair of former Disney executives, Stewart and Irvine had left the Magic Kingdom two years before Bluth to form Aurora Productions. They put together the $6.3 million that Bluth spent making The Secret of NIMH [1982] and the further $4.2 million needed to pay for the prints and advertising.

Bluth delivered. For his adaptation of Robert O'Brien's 1971 Newberry Medal-winning book, Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH, he pulled out all the stops to offer audiences the most impressive display of animated imagination since Disney's own golden age.

Animators, like all craftsmen, produce a product. In doing so, they must balance quality against cost and speed of production.

Since the early 1950s, quality has consistently taken a back seat to the expedients of cost and speed. Filmgoers saw less and less of what Bluth calls "classic" animation.

In the early 1970s, Ralph, (Fritz the Cat) Bakshi emerged as animation's best hope. A strong personality, he openly aspired to be "the new Walt Disney."

In the long haul, Bakshi has proven to be an inconsistent force. A director given to grand themes — American Pop (1981); The Lord of the Rings (1978) — his movies often contain beautiful moments surrounded by disappointing hack work.

Animation fans are now looking to Bluth to set a standard of excellence for the 1980s. Bluth, in turn, has two new features in preparation.

Tuesday [October 5, 1982] he will discuss his art and the craft of classical animation during a special film festival seminar. Scheduled for 8 p.m. in the Robson Square Cinema, it includes a screening of The Secret of NIMH.

The above is a restored version of a Province interview by Michael Walsh originally published in 1982. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Don Bluth's debut feature, an attractive product made with the best of intentions (and a precedent-setting profit-sharing agreement with his employees), received almost universal critical approval. Sadly, The Secret of NIMH achieved only moderate financial success, and Don Bluth Productions eventually filed for bankruptcy. In 1983, Bluth entered video-game history as the designer of Dragon's Lair, the first arcade game in which a player was in control of a quest with movie-quality graphics. His primary focus, though, was feature animation. In 1985, Bluth's group partnered with Seattle-born businessman Morris Sullivan to found the Sullivan Bluth Studios, a Dublin-based animation shop. With Stephen Spielberg aboard as producer, he directed his second feature, the hugely successful An American Tail (1986), and his third, the money-making The Land Before Time (1988). With the exception of the 1997 musical Anastasia, few of Bluth's later cartoon features achieved the box-office success of his work for Speilberg. These included 1989's All Dogs Go to Heaven, the inventive Rock-a-Doodle (1992), Thumbelina (1994), A Troll in Central Park (1994), The Pebble and the Penguin (1995) and Titan A.E. (2000). Currently living in Scottsdale, Arizona, Don Bluth went on line in 2009 with Don Bluth Animation, an educational website that offers tutorials in the art. He's also the force behind Don Bluth Front Row Theatre, a 60-seat venue where the current stage production, Charley's Aunt, runs until September 26. Don Bluth celebrates his 78th birthday today (September 13).