Monday, November 12, 1973.

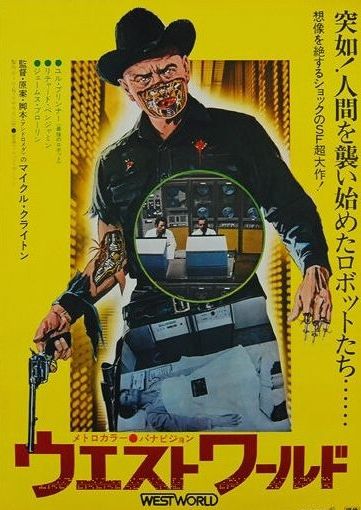

WESTWORLD. Music by Fred Karlin. Written and directed by Michael Crichton. Running time: 88 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: Parents —could frighten children.

FEW MOVIE FANS ARE as fiercely loyal or so infrequently rewarded as the followers of screen science fiction. They follow “their” films through every stage: as proposals, in production, into the theatres and for years afterward on TV and at their many conventions.

Currently, [1973] the talk is of Westworld, an interesting set of ideas rendered bland and less than believable by a novice director. Sadly in this particular case, the author and director are one and the same person.

Inspired by the sophisticated “animatronic” performers in the Disney amusement parks, Michael Crichton has created Delos, the automated resort of the future. For a nominal $1,000 a day, the well-heeled holidayer can take up residence in one of the three recreated ages represented by Romanworld, Medievalworld or Westworld.

Because each of the Delos “worlds” is peopled by preprogrammed automatons, the resort’s human guests can fufill their every desire, be it sensual, sadistic or merely silly. Because of fail-safe electronic technology, no harm can ever come to a living person.

That, at least, was Crichton’s original premise. Shackled by external necessities and troubled by some unresolved internal inconsistencies, his project fails to live up to its promise.

Apparently, the film’s production company, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, wanted a film that could go out to the theatres with the equivalent of B.C.’s family-friendly Mature rating. Unfortunately, the necessity of making Delos acceptable to virtually all age groups effectively pulled the plug on it as an adult attraction.

Originally conceived as the technological equivalent of Kublai Khan’s Xanadu, a pleasure dome with no restraints of any kind, Delos comes off looking like a series of elaborate costume parties arranged by an affluent but unimaginative private high school.

Crichton’s story is centred on Peter Martin (Richard Benjamin) and John Blane (James Brolin), a pair of 30ish Chicago businessmen who are guests at Westworld. They’ve chosen the American frontier environment because they want to recreate the spirit of the Old West.

They spend their days happily gunning down the black-clad Gunslinger (Yul Brynner), while their evenings are filled with barroom brawls and saloon-girl seductions.

What they don’t know is that while they’re playing cowboy, Delos is beginning to experience serious technical difficulties.

For some mysterious reason — the film never really explains why — the robots are slipping out of control. Programmed to menace rather than maim the customers, they are threatening to go on a real rampage.

Westworld is a Frankenstein tale tailored to the 20th century. Unfortunately, the filmmakers didn’t take the time to think it through.

At one point, for example, we hear Blane assure a worried Martin that he can’t possibly shoot another human with his Westworld gun. It’s fitted with a heat-sensing device, he explains. It won’t fire at living bodies.

Conclusion: Robots are cold.

Or are they?

That idea is inconsistent with a later scene in which Martin and Blane spend an evening warmly embracing a pair of saloon-girl robots. Surely the Delos sex machines have to maintain a proper body temperature?

But then they couldn’t be shot, thus closing off one avenue of fantasy — albeit a sadistic one — in a supposedly unfettered fantasy land. (Later, we’ll see a robot manage to kill humans with one of those supposedly fail-safe weapons.)

Perhaps the best-realized item in the film is the Gunslinger’s robot’s-eye view of things. A machine, it sees as a machine might, not in fully resolved pictures, but in square facets of light and dark. The film used here actually was processed through a computer.

Despite some challenging ideas, first-time feature director Crichton fails to make them work. Rather than building suspense and terror like a Hitchcock, he emphasizes the bland and coldly technological, as if he were taking 2001 rather than Psycho as his model.

That was a mistake. Westworld’s real roots are in horror rather than science fiction. Crichton’s film tries to be over-profound, dwelling endlessly on its hardware and inviting the audience to read in the supposedly deeper meanings.

The result is a visually pedantic, unexciting film. Our trip to Westworld is an unrelenting bore.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1973. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Although I was unkind to director Michael Crichton’s debut feature, I was sympathetic to his intentions. At the time, science fiction was emerging as the era’s literature of ideas, and Westworld touched on some interesting trends in the intersection of high-tech and entertainment. I was disappointed that M-G-M had “pulled the plug on it as an adult attraction.” Looking back, I’m reminded that in the mid-1970s the world “adult” was undergoing a transformation within the pop culture. I used it to mean “serious,” an item that might offer audiences an artistic challenge. There was, of course, a parallel entertainment industry that was using the word “adult” as a euphemism for “sexually explicit” content. Crichton’s inquiry into how we might make use of the license — licentiousness? — granted by emerging technologies certainly could be be spun in that direction. No surprise, then, that five years later, porn film director Anthony Spinelli had a major hit with his "adult" feature SexWorld (1978).

Today (October 23, 2016), as the fourth episode of the 10-part HBO cable television series Westworld goes to air, it is interesting to recall the legacy of Crichton’s original film. Actor Yul Brynner returned to reprise his Gunslinger role in a financially successful 1976 sequel called Futureworld, a theatrical feature that did not involve Crichton in any capacity. In 1980, the author took the “creator” credit on Beyond Westworld, a CBS-TV series that ran just five episodes (of which two were never aired). Crichton had better luck in 1984, with his filmed-in Vancouver feature Runaway, another look at the rogue robot theme. In 1990, Crichton offered a variation on the glitchy entertainment experience in his novel Jurassic Park, then wrote the screenplay for director Steven Spielberg’s 1993 movie adaptation. That version of the tale has generated three sequels to date. The technophobia suggested by Crichton in Westworld is now a basic science-fiction trope. Among the most adult — as in serious — considerations was offered up in Joss Whedon’s two-season television series Dollhouse (2009-10), a meditation on modernity worth revisiting on DVD.