Friday, June 7, 1991

JUNGLE FEVER. Music by Terence Blanchard. Written, produced and directed by Spike Lee. Running time: 132 minutes. Restricted with the B.C. Classifier’s warning "frequent very coarse language, occasional violence, nudity and suggestive scenes."

FORGET THE OFFICIAL RHETORIC. In today's U.S., there's one issue.

Race.

The word, printed in letters seven centimetres high, was featured on the cover of May’s [1991] Atlantic Magazine. "When the official subject is presidential politics, taxes, welfare, crime, rights or values. . .” we’re told, "the real subject is RACE."

In an article examining the importance of race in current American political discourse, Washington Post political writer Thomas Byrne Edsall demonstrates how candidates of both parties avoid doing the right thing.

If, as Edsall insists, race is the great issue, then writer-producer-director Spike Lee is well positioned to replace Oliver Stone as Hollywood's official scold.

The subject is at the heart of his work, as fundamental to him as Vietnam anxiety is for Stone.

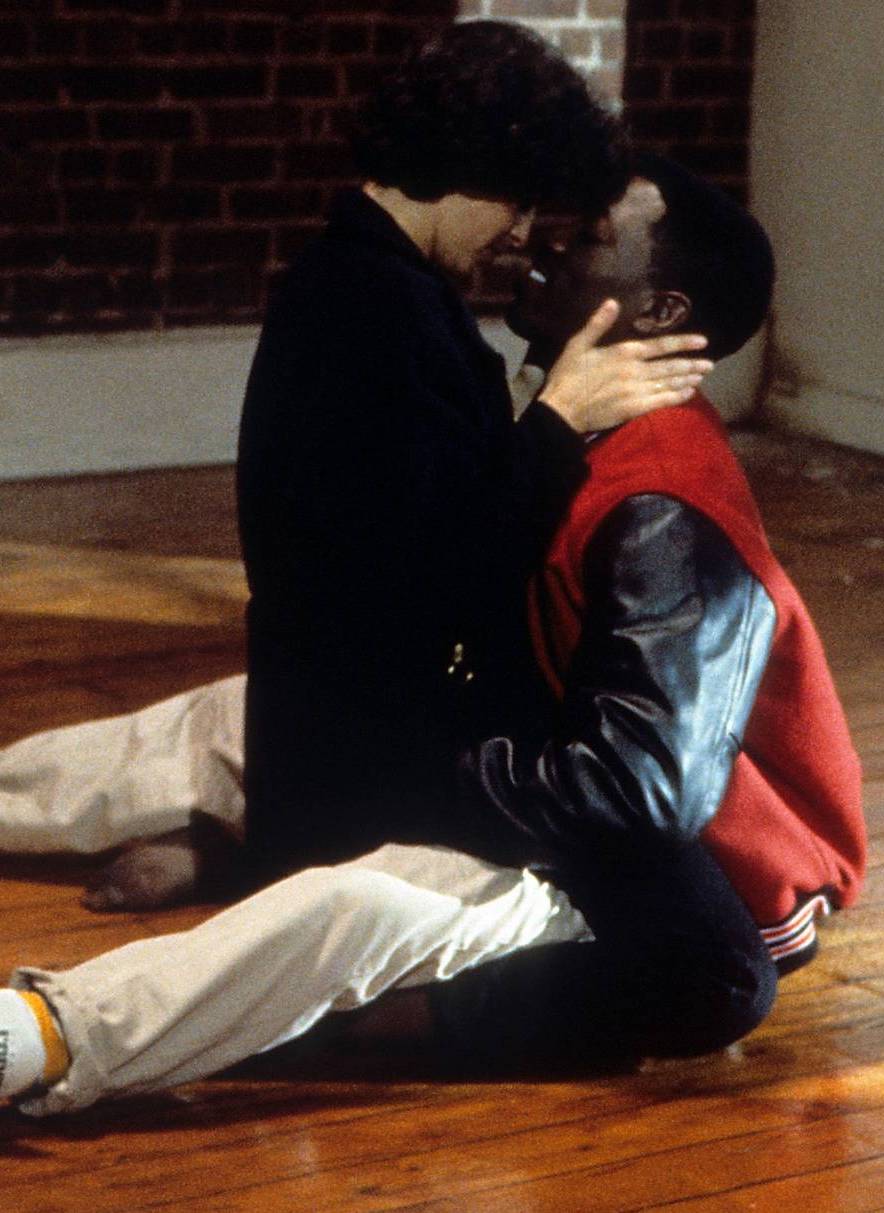

It is the issue in Jungle Fever, Lee's look at a black-white love affair. Its hero, successful New York architect Flipper Purify (Wesley Snipes), is "just a natural black man trying to survive in a cruel and harsh white corporate America."

Despite a happy marriage to an equally successful woman, Purify becomes passionately involved with Italian-American secretarial temp Angela Tucci (Annabella Sciorra). "I've got to admit, I've always been curious about Caucasian women," he tells us.

Like Ollie Stone, Lee speaks for "his generation." Like Stone, he's given to florid overstatement. His in-your-face visual style has more in common with the cartoon-like sex films of Russ Meyer than serious screen drama.

Which is not to say that Lee isn't serious. Unfortunately, in the attempt to be commercial as well as true to his vision, he'll opt for flash rather than substance.

Jungle Fever's major failing is a less-than-convincing romance. Introduced as a Guess-Who's-Coming-to-Dinner paragon, Purify isn't the sort to come on to the help.

Lee would have us believe that the Bensonhurst-born Angie just can’t say no to the challenge in Mr. Wonderful's awkward revelation that "I've never cheated on my wife before."

Though neither seems the type, it's up on his drawing board and down with her panties before you can say "unmotivated plot contrivance."

It is, however, necessary to Lee's purpose. It sets up his examination of just how badly everyone reacts to such liaisons.

Nor does he shrink from some hard truths. "Most of the brothers who've made it have white women on their arms," says a woman in the support group of wronged wife Drew Purify (Lonette McKee).

Colour, Lee makes clear, is a big issue among blacks of both sexes. It's no accident that Angie's Mediterranean complexion makes her virtually the same colour as the light-skinned Drew.

Among African-Americans, Lee insists, racial consciousness is always close to the surface. It's today's issue.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1991. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Here’s a fun fact. Until June 12,1967, interracial marriage was still illegal in 17 of the 50 U.S. states. The word “miscegenation” (racial interbreeding) had been in common use since at least 1863, and laws banning it were part of the fabric of the nation from the beginning. Nor did the racialism that it represents go away with the 1967 Supreme Court decision (Loving v. Virginia) that struck down the remaining statutes barring the conjugal matrimonification of blacks with whites.

Another fun fact: Director Stanley Kramer’s Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner, a romantic comedy in which an interracial couple (Sidney Poitier and Katharine Houghton) announce their engagement to her parents (Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn), was released on December 11, 1967. The picture was nominated for 10 Oscars (including Best Picture) and was a financial success. A positive shift in public attitudes had finally begun.

There was still enough controversy in the concept 24 years along for Spike Lee to make his 1991 feature exploring black misgivings about the idea. Now, though, “no one uses the phrase "jungle fever" anymore,” culture critic Ira Madison III wrote in a 2016 MTV News posting, “so it’s no surprise that after 25 years, the Spike Lee joint Jungle Fever has not aged well.” Sadly, the lede on the above review — “In today's U.S., there's one issue. Race.” — remains true. As for mixed-race marriage, not so much. It’s taken more than 50 years, but movies and television have so normalized diverse couplings that it’s virtually disappeared as an issue. And that’s definitely a step in the right direction.

Looking at Lee: Today’s additions to the Reeling Back archive include four features written, produced and directed by Spike Lee. Included are a musical comedy School Daze (1988); the neighbourhood protest tale Do the Right Thing (1989); an after-hours romance Mo’ Better Blues (1990); and an interracial sex drama Jungle Fever (1991).