Friday, March 28, 1975.

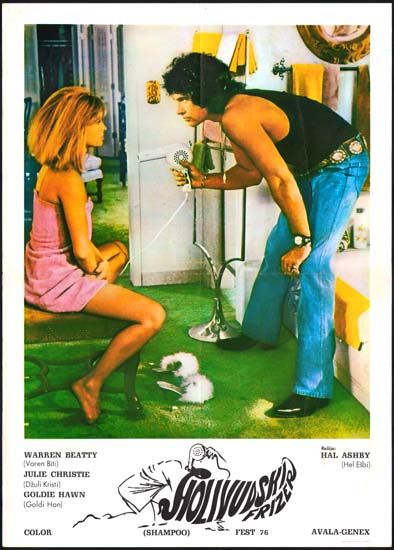

SHAMPOO. Written by Robert Towne and Warren Beatty. Music by Paul Simon. Directed by Hal Ashby. Running time: 109 minutes. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: coarse and suggestive language.

EVERY SEASON NEEDS ITS fashionable picture. Casual moviegoers have to have a film that’s a bit daring — something that will offend Aunt Ada and cause a complaint or two at the provincial classifier’s office — so that they will have something to talk about over the canapés.

To be fashionable, a picture must have elements of social consciousness and some philosophic pretences, something that can be talked about in terms of art. The mass audience wants to be patronizing without realizing that they themselves are being patronized.

Fashionable films don’t have to be good. Pictures such as 1966’s Blowup, The Graduate (1967), Midnight Cowboy (1969), Love Story (1970) and Last Tango in Paris (1972) get by just by being trendy. Although they are all pretty stale pastry today, in their time they won audience approval and made bundles of money, the ultimate reward for fashionability.

This year, being in fashion probably means seeing Shampoo. According to Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times: “The talk and carryings-on (in the film) will enliven a lot of cocktail conversation for the next little while, and Shampoo is one of those movies likely to attract business because it is notorious rather than because it is admirable — because it will be culturally necessary to say you have seen and heard Julie Christie in the Bistro scene.”

Champlin is one of 17 critics whose favourable reviews were reprinted virtually in full in a six-page supplement promoting the picture in a recent issue of the American trade paper Variety. Publications from Family Circle to Screw Magazine were quoted to prove that Shampoo is this year’s big movie.

And what are we wearing this year?

Smugness, mainly, trimmed with self-righteousness and tinted, ever so slightly, with envy green.

Shampoo is the story of a Beverly Hills hairdresser named George Roundy (Warren Beatty). Contrary to the cliché, George is heroically heterosexual. Indeed, at one point in the film, he admits that he went to beauty school so that he could have constant access to women.

Women, apparently, want constant access to George as well. The film opens with his leaving one wealthy customer, Felicia Karpf (Lee Grant), in his bed as he rushes off to visit his girlfriend Jill (Goldie Hawn), a would-be actress.

The action of the picture takes place over two days during which George is attempting to put together the money to open his own shop. It is complicated by his need to sort out his sexual relationships.

So what makes it so fashionable?

The two days under examination — November 5 and 6, 1968 — feature a U.S. presidential election. (Here in Canada, in case anyone has trouble remembering, the federal Liberals swept to power on June 25 on a wave of [Pierre] Trudeaumania.)

The man from whom George hopes to get his financial backing is Felicia’s husband Lester (Jack Warden), a fund-raiser for Republican candidate Richard Nixon. Complicating matters is the fact that Lester’s current mistress is George’s old girlfriend, Jackie Shawn (Julie Christie).

Now, although George has been intimate with both his wife and teenaged daughter Lorna (Carrie Fisher), Lester is the sort of husband who assumes that hairdressers have to be homosexual. He goes so far as to ask George to do him the favour of escorting Jackie to an exclusive election-night celebration.

Absolutely everyone is there, including Felicia and Jill. When a bomb scare breaks up the black-tie affair, most of the characters move on to a second party, a strobe-lit affair for the real swingers where everything is turned on but the television sets.

The TV is on the next morning. As George and Lester confront one another, assessing the previous evening’s emotional damage, we see the victorious Nixon on the tube nattering on about bringing people together.

Shampoo is the second collaboration between screenwriter Robert Towne and director Hal Ashby. (Their previous project, a 1973 Jack Nicholson vehicle called The Last Detail, was filmed in Toronto.)

Both men have done interesting work before. Towne currently [1975] is an Academy Award nominee for his Chinatown screenplay. Ashby is a former film editor who cut several of director Norman Jewison’s movies, including 1966’s The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming, The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) and Gaily, Gaily (1969).

An Oscar winner for his work on Jewison’s In the Heat of the Night (1967), Ashby got his first chance to direct on the Jewison-produced comedy The Landlord (1970).

All of this notwithstanding, people are likely to think of Shampoo as a Warren Beatty picture. Not only did actor Beatty produce it, but he takes credit for co-writing Towne’s script.

The cocktail chatter already suggests that George’s story is really the famously priapic Beatty’s own emotional biography. And who can forget that Beatty and Christie have been an item ever since they co-starred in 1971’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller, filmed in West Vancouver?

His film seems designed to show Americans, currently suffering from a post-Watergate malaise, that everybody has come a cropper since 1968, swingers and manipulators both. Misery has lots and lots of company.

Ashby is not a bad director. Indeed, he showed a real flair for bizarre comedy with his Harold and Maude (1971). Come to think of it, Shampoo is billed as comedy, though I can’t recall actually laughing.

There are no laughs because, in the final analysis, Shampoo is a lightweight tragedy. It’s slightness is accentuated by the heavy burden of significance that everyone seems determined to drape over its shoulders.

If it does win a large audience, it won’t be because it's great cinema, but because it feeds upon the with-it mood of the moment.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1975. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Although 1975 ended up being the year of Jaws, the top-grossing film with record-setting ticket sales of some $260 million, the R-rated Shampoo managed a more-than-respectable fifth place finish, earning about $60 million on its $4 million cost. It was a major triumph for its star, Warren Beatty, who had been coasting since his first big hit, director Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967). Shirley MacLaine’s kid brother was able to follow success with success, making his directorial debut with 1978’s Heaven Can Wait. A remake of the 1941 fantasy Here Comes Mr. Jordan, its box-office performance gave Beatty the opportunity to write, produce, direct and star in his most political feature of the 1980s, Reds.

A lifelong “Hollywood liberal,” Beatty had been a fund-raiser for Democratic Senator George McGovern’s 1972 presidential run — lost to Richard Nixon — and there was a political subtext to his role in director Alan J. Pakula's 1975 thriller The Parallax View, in which he played a reporter investigating a presidential assassination. Reds, by contrast, was an historical drama celebrating the life of American Communist John Reed, a journalist who covered the Russian Revolution. Released shortly after the inauguration of the right-wing Ronald Reagan, it was deemed a brave act and Hollywood rewarded Beatty with a best director Oscar for his moxie. Then came Ishtar (1987), the movie title that became a synonym for cinematic disaster.

Beatty bounced back in 1990, producing, directing and starring in the comic-strip action comedy Dick Tracy. The release of his 1998 political satire Bullworth, the story of a disillusioned populist politician, was accompanied by much speculation that the opinionated actor might follow former Hollywood performer Reagan’s example and run for president. Instead, he starred in the 2001 feature Town & Country, an even bigger financial disaster than Ishtar. Unseen on screen since, he has spent the last 15 years working on a film about reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes. (In that time, actor Arnold Schwarzenegger had time for an eight-year political career — 2003-2011— as governor of California before returning to the movies.) Beatty’s return, as producer, writer, director and star (playing Hughes) of Rules Don’t Apply, is scheduled for release on November 23, 2016. Where he plans to spend this election night (November 8) has not made the news.