Friday, September 18, 1992.

HUSBANDS AND WIVES. Music: Bernie Leighton (piano). Written and directed by Woody Allen. Running time: 107 minutes. Rated 14 Years Limited Admission with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: some very coarse and suggestive language, occasional nudity and suggestive scenes.

POINTLESS. PAINFUL. PURLOINED.

Rushed into theatres to take advantage of writer-director Woody Allen’s recent personal publicity [1992], Husbands and Wives is the pits. A mock documentary, the film lacks the saving grace of substance to accompany its stolen style.

Parody, it seems, is the last refuge of the creatively destitute. Having taken his shot at interwar expressionism (1991’s Shadows and Fog), the increasingly tedious Allen returns to the ever-popular 1960s to play at cinéma vérité.

Watch as Woody (Zelig) Allen turns himself into Allan (Warrendale) King. Husbands and Wives, with its hand-held camera’s-eye view of two troubled marriages, is his fictional remake of King’s urban true-life adventure A Married Couple (1969).

Watch with caution, though. If you must see it, sit well back in the auditorium.

Allen, unlike the thoroughly professional King, seems to think that the physical essence of vérité is constant, jerky camera movement.

The physical result of this for me was a nasty headache. Ninety minutes into the picture, I was suppressing nausea.

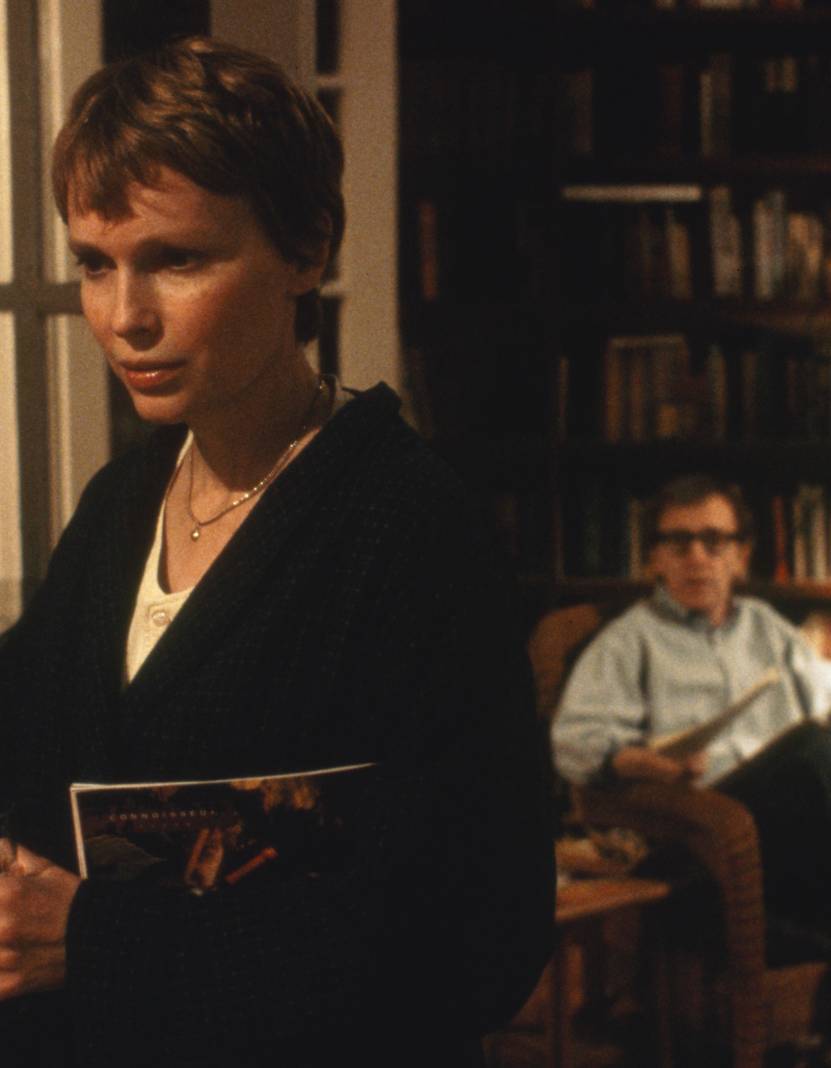

Filmgoers willing to risk such potential discomforts are introduced to Gabe (Allen) and Judy Roth (Mia Farrow). A New York couple, they’ve allowed a documentary filmmaker (Jeffrey Kurland) total access to their lives.

A film crew is present to record Judy’s extreme reaction to the news that the Roth’s close friends Jack (Sydney Pollack) and Sally (Judy Davis) are separating. In the process, Allen “rediscovers” what King observed during his 10 weeks in the Toronto home of his Married Couple, Billy and Antoinette Edwards.

The omnipresence of the camera forces feelings to the surface. Put “on stage,” people allow their “real feelings” to develop more fully, King told me in a 1970 interview.

Allen, less honest, is merely simulating truth for the purpose of entertainment. Here, there is the additional titillation of seeing him, in character, admit an attraction to younger women. In his role as college writing instructor Gabe Roth, he assures us that “I’ve never acted on it.”

Recycling ideas as well as film styles, Manhattan’s philosopher-comic offers yet another of his sweet-and-sour meditations on the marital bond.

“Maybe, in the end, it was better not to expect too much out of life,” self-absorbed Gabe tells us, echoing Annie Hall’s Alvy Singer.

“My heart does not know from logic,” he whines, wilfully mistaking lust for love. Woody’s world, populated by “carnivorous women” and balding men with oral-sex fixations, really is a dreary, dated place.

“Life,” says Gabe, quoting his sexually aggressive student Rain (Juliette Lewis), “doesn't imitate art, it imitates bad television.” Much like Husbands and Wives.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1992. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Readers of newspaper entertainment pages in 1992 were well aware of the fact that Woody Allen’s 13-year relationship with actress Mia Farrow ended badly. In January 1992, according to published reports, Farrow discovered nude photos that her 56-year-old companion had taken of her adopted daughter, 20-year-old Soon-Yi Previn. The story, which later included allegations that Allen had molested Previn’s then-seven-year-old stepsister Dylan Farrow, played out in the headlines and the courts for the next year. The couple's split took place during the making of Husbands and Wives, a fact that the film’s distributor, Tri-Star Pictures, used to its advantage. The troubled marriage drama was put into wide release immediately, an unusual strategy for a “serious” Woody Allen production at the time.

Mia Farrow was destined to be a celebrity. One of seven children born to Hollywood director John Farrow and actress Maureen O’Hara, she made her big screen debut at the age of 13, an uncredited extra in her father’s 1959 feature John Paul Jones. She honed her craft on ABC-TV’s prime-time soap opera Peyton Place (1964-1966), playing the bookish daughter of the show’s star, Dorothy Malone. In 1964, during the show’s first season, she began an affair with singer-actor Frank Sinatra, a man 29 years her senior. They married in 1966 and divorced in 1968, after Farrow signed on to play the devil’s consort (and ultimate put-upon wife), in director Roman Polanski’s adaptation of Rosemary’s Baby. It was her breakthrough feature role, and the horror movie’s June release followed her February flirtation with Transcendental Meditation. During her much-publicized visit to an Indian ashram, she shared spiritual time with The Beatles.

Returning to Los Angeles, she began an affair with the Oscar-winning composer André Previn, a man 16 years her senior. She bore him two children before their marriage in 1970, and a third in 1974. Farrow divorced Previn in 1979, the year she began her 13-year-long relationship with Woody Allen, a man 10 years her senior. It was a union that produced one son and 13 feature film collaborations.

Forests have been felled to produce the paper for the many newspapers, magazines and books that have chronicled the Farrow tale. Raised a Roman Catholic, her story includes good works — in 2000, she became a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador advocating for human rights in Africa — and political engagement — in 2016, she endorsed self-described socialist Bernie Sanders for U.S. president. Today (February 9), she turns 72.

For the record: The 13 films written and directed by Woody Allen that feature Mia Farrow are A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy (1982); Zelig (1983); Broadway Danny Rose (1984); The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985); Hannah and Her Sisters (1986); Radio Days (1987); September (1987); Another Woman (1988); New York Stories (1989); Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989); Alice (1990); Shadows and Fog (1991); and Husbands and Wives (1982).