Monday, March 22, 1982.

THE BOMB WAS REAL. Nearly 100,000 litres of water would explode into an expensively dressed film set when it went off, destroying it for the benefit of the Panavision cameras.

Strictly speaking, placing the charge was a job for the demolitions expert. But the bomb was an important element of the shot and, says Charles Jarrott, "I knew what I wanted it to look like."

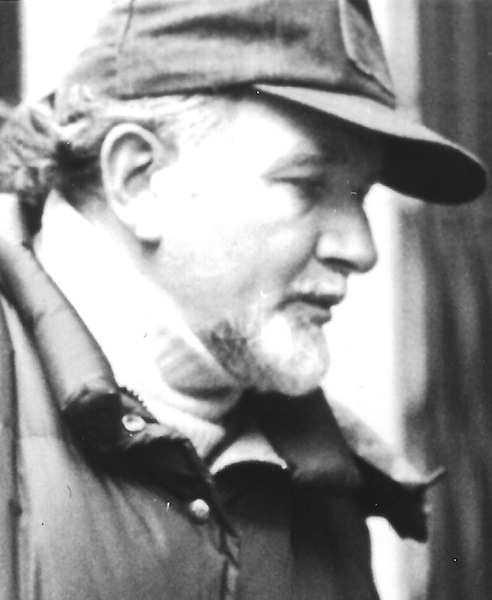

It was Jarrott, the film's director, who attached the explosive package to the glass-walled tank. That way, if anything went wrong, "I'd have no one to blame but myself."

As it turned out, both the bomb and the shot worked. They provided the British-born filmmaker with a spectacular bit of action footage for The Amateur, Jarrott's 10th theatrical feature and his first for a Canadian producer.

No stranger to the Great White North, Jarrott arrived here first in 1953 as a young actor on tour with an English theatre company. He remained for the next six years, eventually becoming a CBC-TV drama director and a Canadian citizen.

In the mid-1960s, Jarrott became involved with Dan Curtis, an American producer who was planning to use the then-new videotape technology for a series of prestige made-for-TV dramas. Included was 1968's The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, with Jack Palance cast in the title roles.

Location shooting was planned for New York. But, when unrelated union troubles threatened to shut down the ABC-TV production facilities, "I suggested Canada," Jarrott told me in an interview. As a result, the CBC became Curtis's co-producer, and Toronto proved that it could manage a credible imitation of Victorian London.

Analysts looking for themes in Jarrott's work might consider personal responsibility, a strong element in almost all of his films. In his version of the Robert Louis Stevenson tale, for example, Jekyll is less the victim of an experiment gone wrong than an addict who refuses to control his craving.

"Evil," Jarrott says, "is a very powerful drug."

Following the Jekyll/Hyde project, the director was given responsibility for some big-budget theatrical epics. Anne of the the Thousand Days (1969) teamed Richard Burton with Canadian actress Geneviève Bujold, while 1971's Mary, Queen of Scots brought together acting powerhouses Glenda Jackson and Vanessa Redgrave.

Less successful than his historical dramas was an all-star musical remake of 1937's Lost Horizon (1973). The marriage of James Hilton's period fantasy of Shangri-La with Burt Bacharach's songs was not a happy one.

For a change of pace, he took on the intimate, almost interior drama of The Dove (1974). The true story of Robin Lee Graham, a young man who sailed around the world in a small boat, the film was "an exercise in logistics," Jarrott recalled. The Dove was produced by actor Gregory Peck, who "desperately wanted to make a picture about an American winner."

Logistics also were a major consideration in the director's 1977 assignment, The Other Side of Midnight, based on on a best-selling novel by Sidney Sheldon.

Responsibility has had a lot to do with his continuing association with Walt Disney Productions. Since the 1966 death of its founding father, the Disney organization has been "trying to reach a much wider audience," Jarrott says. In recent years the studio has made an effort to find directors with fresh approaches to family filmmaking.

In 1976, he directed a film called Pit Ponies (also known as Escape from the Dark) in England for Disney. Set in a 1909 Yorkshire coal mining town, it was "an almost Marxist drama," Jarrott says. Though its U.S. release title — The Littlest Horse Thieves — was "so cute I could spit," the picture remains "one of my favourite films."

Jarrott recognized that "it would be irresponsible to do something not right for the Disney name." The studio has asked him to take other assignments, including 1980's The Last Flight of Noah's Ark, a film that reunited the director with leading lady Geneviève Bujold.

Last year [1981], Jarrott's specialty was spies. Condorman, a Disney release, spoofed James Bond-like secret agent movies, while his current The Amateur is a solid action-thriller.

Being a Canadian with international directorial credits makes Jarrott attractive to a lot of Capital Cost Allowance-conscious domestic producers. He remains gentlemanly about the projects he's turned down, saying only that "a lot of people in this country have set out to make movies for the wrong reasons."

By contrast, Jarrott is full of praise for Torontonians Garth Drabinsky and Joel Michaels, producers of The Amateur. "They want to be able to take pride in the work they're doing," he says.

With such films as 1978's The Silent Partner, The Changeling (1980) and Tribute (1980) to their credit, "they want to make a good product." As a result, says Jarrott, he was able to return to Canada to make a movie "with a bit of class."

The above is a restored version of a Province interview by Michael Walsh originally published in 1982. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: I first became aware of Charles Jarrott's Canadian connections reading the press notes provided by film distributor Pan Canadian at the time of The Amateur's release. That part of the story wasn't mentioned in the sketch biographies that accompanied his Hollywood studio pictures. I was fascinated to learn that he'd worked as a young actor in the early days of CBC television, and that he'd learned to direct in the Corp's Toronto studios. He was recruited into a directorial apprenticeship program by the legendary Sydney Newman, at that time head of CBC drama. Jarrott returned to England in 1959, the same year that Newman became head of drama for Britain's ABC-TV. Their association continued, with Jarrott distinguishing himself as a director of small screen dramas until making his feature debut with 1969's Anne of the Thousand Days.

At the time of our 1982 conversation, Jarrott's big-screen filmmaking career was coming to an end. After the box office failure of The Amateur, he made one more theatrical feature, directing Nicolas Cage in 1986's The Boy in Blue. A sports biography, it told the story of Ned Hanlan, the Canadian athlete who became a world-champion sculler in 1880. Afterwards, he segued into a career as TV-movie biographer, turning out six such features in quick succession: Ike (1986; about Dwight Eisenhower), Lyndon Johnson (1987), I Would Be Called John: Pope John XXIII (1987), Poor Little Rich Girl: The Barbara Hutton Story (1987) and The Woman He Loved (1988; about Wallis Simpson and Edward VIII). Later, he added Lucy and Desi: Before the Laughter (1991) and A Promise Kept: The Oksana Baiul Story (1994) to the list.

Among his late credits are two made-for-TV holiday movies — Yes Virginia, There Is A Santa Claus (1991) with Charles Bronson, and The Christmas List (1997), starring Mimi Rogers — both shot in Vancouver. Also filmed here was his adaptation of the Sidney Sheldon novel, A Stranger in the Mirror (1993). Charles Jarrott died in 2011 at the age of 83.

See also: My reviews of director Jarrott's Anne of the Thousand Days (1969), and The Amateur (1981).