Monday, September 13, 1992

ADAM'S RIB (Rebro Adama). Written by Vladimir Kounine. Based on the book House of Young Women, by Anatole Kourtchatkine. Music by Vadim Khrapatchev. Directed by Viatcheslav Krishtofovitch. Running time: 75 minutes. In Russian with English subtitles. Rated Mature with the B.C Classifier’s warning "occasional coarse language and nudity." In Russian with English subtitles.

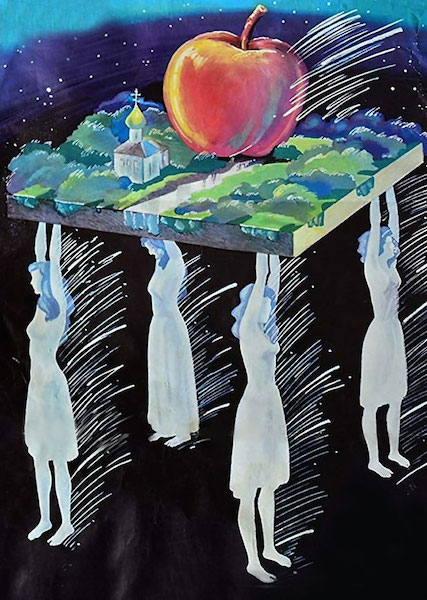

POSTER PORTRAITS OF ADAM and Eve adorn the bathroom door in Nina Elizarovna's three-room Moscow apartment.

As it turns out, though, the sons of Adam have long been absent from this particular corner of the Workers' Paradise. "Let's be realistic," says Nina's adult daughter Lida (Svetlana Riabova), "we can't rely on any men."

Nina (Inna Tchourikova), a Soviet working woman, shares her bathroom with Lida, Lida's teenaged sister Nastya (Macha Golubkina) and their ailing granny (Elena Bogdanova). Together, they cope.

Adam's Rib, their finely nuanced story, is a unexpectedly familiar bit of socialist realism. Here's a domestic comedy-drama that might be the work of a Ken (Riff Raff) Loach or a Mike (Life Is Sweet) Leigh.

Instead, the perpetrator is Kiev-born Ukrainian director Viatcheslav Krishtofovitch. His adaptation of Anatole Kourtchatkine's book House of Young Women affirms both the fascination and the simple dignity of ordinary life.

Six months short of her fiftieth birthday, twice-divorced Nina is being courted by shy, essentially decent factory supervisor Evgeny Anatolievitch (Andrei Tolubeev). She doesn't hold out a lot of hope for the relationship.

"My mother's paralyzed," she says, as much to herself as to him. "I have two grown daughters by very different husbands."

Daughters, she might have added, with man troubles of their own. Lida, an office worker, is involved in a dead-end affair with her married boss.

Nastya, her tough-talking, 15-year-old half-sister, has been intimate with a soulful, unambitious ex-paratrooper. The complications arising from this will be discussed at Granny's birthday celebration, a gathering that will bring together a selection of former and potential husbands.

With understated wit and considerable compassion, director Krishtofovitch offers a human comedy with an emphasis on the human. Historically, his Adam's Rib is one of the last films that we can call "Soviet.”

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1992. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Released to Moscow theatres in January 1991, Adam’s Rib was screened at the Toronto International Film Festival and the New York Film Festival in September. The U.S.S.R. was formally dissolved on December 26, and with it a cinematic era ended. Movies continued to be made, of course. Since 1992, international distributors and film festival programmers have had to contend with the existence of 15 “new” national cinemas.

Or not. From the beginning, Hollywood has been an expert at the practice of disaster capitalism. The Los Angeles-based industry took advantage of the serious blow to European film producers during and after the two world wars to expand its markets. In the late 1920s, it used a disruptive technology — sound — to restrict foreign filmmakers' access to the American market. Nor can we forget that, in what can only be described as cultural imperialism, the moguls have always considered Canada (nominally a sovereign state) as part of their “domestic” market. When Canadian artists became interested in the creation of their own cinema in the 1960s, Hollywood made use of its political and economic influence to insure that the result would be a conveniently-located branch plant industry.

Soviet Cinema was important. Over the years, I’ve managed to see a lot of good examples, including the Eisenstein classics Battleship Potemkin, Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible, as well as the pioneering 1924 sci-fi feature Aelita: Queen of Mars. As a teenager, I was fortunate enough to see such eye-opening dramas as The Cranes Are Flying, The Ballad of a Soldier and the epic And Quiet Flows the Don. Later, during my years as a professional film critic, fewer pictures were on offer. I published just 15 reviews of Russian-language movies because that was what was available in the market my newspaper covered. And, yes, it was limiting. Assessing a picture such as Vyacheslav Krishtofovich’s Adam’s Rib, I had no idea if the director’s apparent feminism was typical of his other work (which I’d not seen) or part of a trend in Russian movies (that I’d not seen). The best I could do was compare him to such kitchen-sink British directors as Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. Call it “best guess journalism.”

Soviet Cinema: Features in today’s Russian-language film package include director Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1966 historical epic Andrei Rublev, Alexander Zarkhi’s 1981 biographical romance Twenty Six Days from the Life of Dostoyevsky, Pyotr Todorovsky’s 1983 drama Wartime Romance, and Viatcheslav Krishtofovitch’s 1990 domestic comedy Adam’s Rib.