Wednesday, July 14, 1983

TWENTY SIX DAYS FROM THE LIFE OF DOSTOYEVSKY (Dvadtsat shest dney iz zhizni Dostoevskogo). Written by Vladimir Vladimirov and Pavel Finn. Music by Irakli Gabeli. Directed by Alexander Zarkhi. Running time: 87 minutes. Rated Mature entertainment. In Russian with English subtitles.

IT'S NOT JUST CALIFORNIA film school graduates who are nostalgic for the dream factories of yore. Mosfilm, the biggest movie studio in the Soviet Union, is making the kind of pictures that used to be made at M-G-M.

Take Alexander Zarkhi’s Twenty Six Days in the Life of Dostoyevsky, for example. Though thoroughly Russian, it is scripted, paced and cast like a Hollywood biopic from the 1940s.

The time is October, 1866. “Poor Fyodor,” says a mourner at a funeral. “First his wife, and now his brother.”

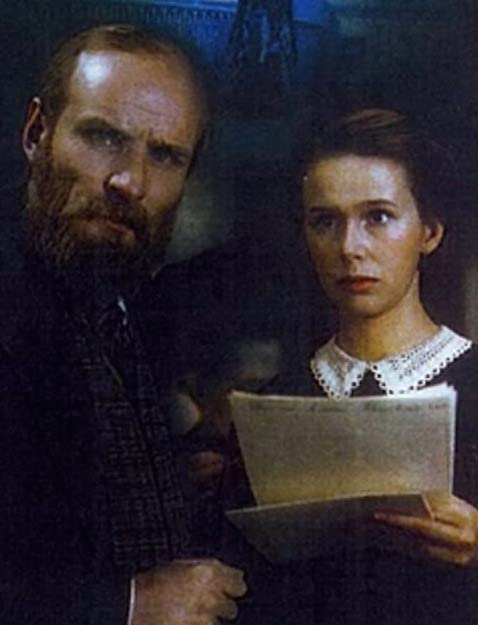

Historically, those particular deaths occurred in 1864. The idea, of course, is to set up the situation concisely — Dostoyevsky (Anatoly Solonitsyn) is despondent, debt-ridden and up against an impossible publisher’s deadline — and then get on with the story.

A friend suggests that Fyodor might just make his deadline with the help of a stenographer. The girl who arrives at his door is Anna Grigorievna Snitkin (Evgenia Sim Simonova), a spunky 19-year-old who is in awe of the great man.

Hollywood, in its heyday, would have given us Spencer Tracy and June Allyson. Zarkhi, who has been a feature filmmaker since 1930, takes essentially the same approach, offering us an entertainment that is less literary history than a larger-than-life romance.

Anna sees the crotchety novelist as "lonely . . . old. I think he’s 45.”

For him, she’s a badly needed tonic.

With her help and encouragement, he channels his unhappiness into a new novel, The Gambler. Completed in just 26 days, it tells the story of the gambling addiction that has put him in poverty’s way.

The film is lit, for the most part, like one of Isaac Brodsky’s Soviet Realist paintings, giving Twenty Six Days a properly Russian look. Zarkhi’s handling of his material, on the other hand, is downright American.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1983. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: It was easy to think of Mosfilm, the Moscow-based Soviet moviemaker, as Russia’s M-G-M. In fact, its founding predated that of the American studio, the corporate result of the 1924 merger of Metro Pictures, Goldwyn Pictures and Louis B. Mayer Pictures. Mosfilm was established in 1920, the result of the 1919 nationalization of the studios founded by Russian film pioneers Aleksandr Khanzhonkov and Joseph Ermoliev. As it turned out, the Soviet state and Hollywood’s moguls were in complete agreement when it came to harnessing cinematic creativity. Both believed that corporate concentration was the way to go. I can imagine Mayer nodding approvingly when Vladimir Lenin declared that “while the people are illiterate, the most important forms of art for us are cinema and circus.”

Though the M-G-M tale is a familiar one to film buffs, Mosfilm’s full story remains to be told in English. We know bits of it, because its early history includes the works of cinema great Sergei Eisenstein, director of such landmark features as 1925’s The Battleship Potemkin, Alexander Nevsky (1936) and the two-part Ivan the Terrible (1944/1946). Yet to be fully chronicled are the fraught years of 1941 to 1944, when the German Wermacht laid siege to Moscow, and Mosfilm was evacuated to Alma-Ata in Kazakhstan.

The studio came to international prominence again in the 1960s with the emergence of such talents as King Lear director Grigori Kozintsev (Hamlet; 1964), Sergei Bondarchuk (War and Peace; 1966-67) and Andrei Tarkovsky (Andrei Rublev; 1966). LINK <> In 1972, the latter director’s adaptation of Stanislaw Lem’s novel Solaris proved that Soviet science fiction could be as stunningly stupefying as that of Stanley Kubrick’s collaboration with Arthur C. Clarke, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

After a decade of disastrous business decisions, M-G-M filed for bankruptcy in 2010. The entity that re-emerged seven weeks later was a spent force historically. By contrast, Mosfilm survived the dissolution of the Soviet Union and returned to private ownership. It was still in business as of last Monday (June 1, 2020), when the London-base architect Stanton Williams announced that it has been contracted to design a new, 30,000 square metre building for the century-old company.

Soviet Cinema: Features in today’s Russian-language film package include director Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1966 historical epic Andrei Rublev, Alexander Zarkhi’s 1981 biographical romance Twenty Six Days from the Life of Dostoyevsky, Pyotr Todorovsky’s 1983 drama Wartime Romance, and Viatcheslav Krishtofovitch’s 1990 domestic comedy Adam’s Rib.