Sunday, July 25, 1974

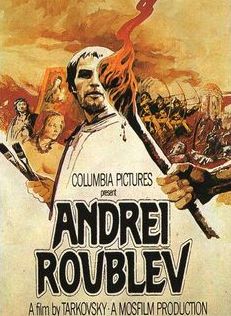

ANDREI RUBLEV. Co-written by Andrei Mikhalkov-Konchalovsky. Music by Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov. Co-written and directed by Andrei Tarkovsky. Running time: 166 minutes. In Russian with English subtitles. Rated Mature.

IN HIS JUST-PUBLISHED [1973] book The Gulag Archipelago, Soviet author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn suggests that fear is part of life in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Sudden arrest, interrogation and lengthy incarceration is possible at any moment. The spectre of the Gulag — the Soviet penal system —hangs over every citizen.

Solzhenitsyn’s opinion is borne out with remarkable clarity in the Eastern bloc films on view in this year’s [1974] Varsity Festival, a spectre most visible in director Andrei Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev.

Begun over a decade ago [1962] in the Soviet Union, Tarkovsky’s feature offers allegorical comment on modern Russian history and the growth of the spectre. Set in the 15th century, it is an a episodic look at the life of the ikon painter Rublev (Anatoly Solonitsyn).

The film, according to its prologue, is “a contemporary interpretation of spiritual and artistic development amid adversity."

Since its director is on the record as having said “I do not understand films that are purely historical with no relevance to the present,” a pointedly political reading of his film is not so very fanciful.

Tarkovsky, who collaborated with another director (Andrei Mikhalkov-Konchalovsky) on the screenplay, follows Rublev from 1400 to 1423. A cloistered monk, he wants to pursue his art and find his way to salvation without involving himself with the outside world. Rublev’s Russia is ruled over by the Grand Prince Yury (Yuriy Nazarov), whose lands are laid waste by his cruel brother. In allegorical terms, the prince can be seen as the modern Soviet government, and his brother as the ever-present spectre of the Gulag.

Rublev, the intellectual, prefers to look away. When he sees an irreverent jester (Rolan Bykov) arrested, he decides that it served him right. The artist’s interest is in higher things.

He accepts the invitation of renowned painter Theophanes the Greek (Nikolai Sergeyev) to help decorate a cathedral, and finds the man to be an embittered pessimist. They debate theological issues, and Rublev offers the ingenuous opinion that “Russians must be reminded that they are one people.”

Whether he acknowledges it or not, Rublev is part of an intolerant system. One evening, he comes upon a village in the midst of a naked midsummer revel. Before he can think what to do, he is captured and tied to a post.

Enjoying their pagan fertility rite, the villagers mean him no harm, but fear that, unfettered, he “might call the monks to enforce (his) faith.” Before long, Marfa (Nelly Snegina), a sympathetic young woman, releases him. The next day, he passes by again and sees the Prince’s men attack the village, murdering his liberator’s husband and pursuing the nude girl into the river.

Director Tarkovsky, the son of Russian poet Arseni Tarkovsky, made his initial international impact with 1962’s Ivan’s Childhood, the lyrical story of a boy growing up during the Second World War. For Andrei Rublev, he reverts to a more traditional (and rather more ponderous) Soviet film style in order to achieve the classical epic effect.

In production between 1964 and 1967, the film was suppressed until 1971. It found its way to the Soviet audience at approximately the time that Tarkovsky started work on his third feature, the $70-million science-fiction epic Solaris, Russian cinema’s answer to 2001: A Space Odyssey.

It may be that the Mosfilm studio authorities thought the future would provide Tarkovsky with less inflammatory inspiration than the past. Officially, Rublev’s release was held back because of its scenes of violence and brutality.

At one point, the prince’s brother betrays an entire city to a band of savage Tartars. After sacking the cathedral, the Tartar chief (Balot Beyshenaliyev) looks on while his Russian allies torture one of Rublev’s assistants. “Even without us,” he muses, “you can cut each other’s throats.”

At another, the prince’s men pursue the artist Theophanes and his assistants. The Greek has made the mistake of designing a house to suit his own artistic vision, rather than to the prince’s more garish specifications. For his trouble, he and his followers have their eyes gouged out, and are left for dead in a forest.

Rublev attempts to rationalize it all away. “Evil is part of human nature,” he declares in a tortuous theological argument. “When you attack evil, you attack human nature.”

Tarkovsky can offer no solution to the sorrows of Mother Russia and the Soviet bloc. Unlike so many young American filmmakers, he has no enthusiasm for revolution as a panacea and even if he did, such mischief-making would hardly be allowed.

Instead, what he preaches is survival. Rublev sees that all around him is corruption, and yet despite every adversity, life renews itself, and youth often dares the impossible.

In the film’s final dark episode, Rublev sees one young man, the bellmaker Boriska (Nikolai Burlyayev), risk all and triumph. Through him, he is able to make his own leap of faith and find meaning in his existence.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1974. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Just to be clear, I am a Marxist. Specifically, a Groucho Marxist, the sort of contrarian who agrees with the American comedian’s famous assertion: “I don’t want to belong to any club that would have me as a member!” And that makes it difficult to resist the urge to irreverence in the face of an established critical consensus that views Andrei Arsenyevich Tarkovsky as one of the greatest and most influential directors in the history of world cinema. According to a readable British Film Institute introduction to his work, Ingmar Bergman considered him “the greatest of them all.” What could I possibly add to that?

The above review was written in 1974, nearly 30 years into the confrontation between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. known as “the cold war.” What I saw on the screen — the version of Andrei Rublev that played Vancouver was at least 30 minutes shorter than the original Russian release — suggested that its director was the living embodiment of the popular notion that Slavs were a morose, melancholy, soulful people, by nature prone to pessimism and a dark world view. Yes, that’s a terrible racial stereotype. On the other hand, have you ever really listened to the music of Modest Mussorgsky, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky or Sergei Prokofiev? Not a lot of laughter in evidence.

The son of a poet, Tarkovsky entered his teen years during the Great Patriotic War, an experience that he drew upon for his first feature film, 1962’s Ivan’s Childhood. Its success — a Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, the Golden Gate Award from the San Francisco International Film Festival — made Andrei Rublev possible. An expensive historical epic, it was something of a problem for Soviet authorities and, not surprisingly, found champions in the West. Did I mention that there was a cold war going on? The product of an embattled, unbending artist, Andrei Rublev was a metaphor-rich vision for the freedom-loving critical cognoscenti.

That it got made at all was a wonder that wasn’t closely examined at the time. Of course we all knew that the Soviet cinema production system was controlled by the state, and that movies existed to serve a public good that was defined by shadowy unions and academies. From within such constraints, though, surprises emerged, as well as works that were legitimately artistic. A visitor from another planet might have found it an interesting contrast to the Hollywood system, were directors had complete freedom to follow their own inspiration, so long as they completed their films on time, within budget and in a form designed to turn a profit for the producers. Within that system, my job was to assess the entertainment value of the industry’s offerings, not suggest that the honesty of the content might be compromised by its basic profit motive.

Tarkovsky completed two science-fiction films within Russia’s “alternative” system, both of them considered genre classics by serious cinema scholars. Solaris (1972), based on the Stanislaw Lem novel, is set aboard a space station orbiting a sentient planet. Stalker (1979), based upon the novel The Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, is a prescient tale of ecological collapse. In 1979, he took his leave of the Soviet system, though not his Russian style. Nostalghia (1983), told the story of a Russian writer in Italy longing for his homeland, and his last film, 1986’s Sacrifice, is set at a family gathering that takes place just as the Third World War is breaking out. Shortly after its completion, Tarkovsky died of lung cancer at the age of 54. A cinema poet, he remained true to his vision, one with not a lot of laughter in evidence.

Soviet Cinema: Features in today’s Russian-language film package include director Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1966 historical epic Andrei Rublev, Alexander Zarkhi’s 1981 biographical romance Twenty Six Days from the Life of Dostoyevsky, Pyotr Todorovsky’s 1983 drama Wartime Romance, and Viatcheslav Krishtofovitch’s 1990 domestic comedy Adam’s Rib.