Thursday, April 25, 1985.

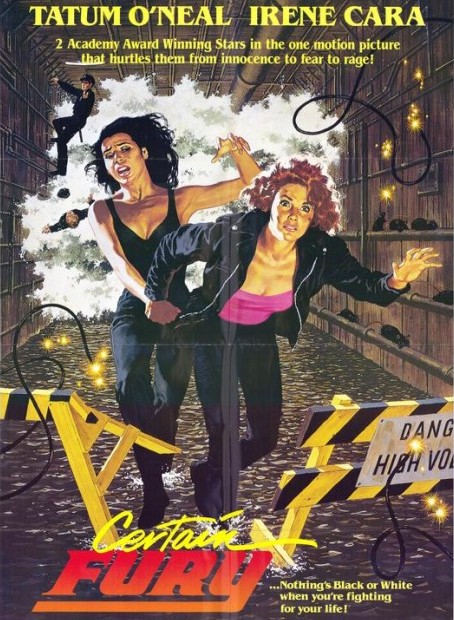

CERTAIN FURY. Written by Michael Jacobs. Music by Bill Payne, Russ Kunkel and George Massanburg. Directed by Stephen Gyllenhaal. Running time: 88 minutes. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: Some gory violence.

"OKAY, GIRLS," SAYS A police matron at the beginning of Certain Fury, "let's move it on out." As the sullen female prisoners entered the courthouse, I thought of Linda Blair and the value of an Academy Award.

A supporting actress nominee at 14, Blair has grown older without growing better. Today [1985], the child who was so impressive in The Exorcist works in B-budget women's prison pictures (Chained Heat), urban violence epics (Savage Streets) and bad taste comedies (Night Patrol).

In the current film, hard-looking young women are filing past an officer who calls the roll. “Scarlet McGinnis . . .”Blair was one of her year's also-rans. She lost the 1973 Oscar to Ryan O'Neal's 10-year-old daughter Tatum, the youngest-ever Academy Award winner for her performance in Paper Moon.

O'Neal was the winner, and her career was expected to soar. Her work in The Bad News Bears suggested that she would be one of cinema's bright lights in the 1980s.

But look. Here she is slouching past the camera in a worn leather jacket and a streetwalker's miniskirt in a movie that is beginning to look like a B-budget women's prison picture.

More names are called out, and more girls pass by. “Tracy Freeman . . .”

Though accurately billed as an Oscar winner, Irene Cara was honoured for her music rather than her acting. (She shared a song-writing award with Giorgio Moroder for the tune Flashdance. . . What a Feeling.)

When violence erupts in the Certain Fury courtroom, Tracy (Cara), a mixed-up middle-class black, finds herself on the run with "illiterate white-trash whore" Scarlet (O'Neal). Even before the first racial epithets are exchanged, though, film buffs will recognize in first-time feature director Stephen Gyllenhaal's pursuit drama an uncredited remake of 1958’s The Defiant Ones.

Maybe screenwriter Michael Jacobs saw the dramatic potential in changing his antagonists from men to women, and the setting from Southern rural to inner-city urban. Rather than seize that opportunity, though, he settles for formula plotting, producing not a vital social-consciousness thriller, but another cheapjack, mean streets melodrama.

O'Neal and Cara both act as if the dreary Miss Blair were their common role model. They splash through sewers, brandish weapons, beat off lowlifes and scream out their lines with desperate energy rather than believable feelings.

Filmed locally — Vancouver and New Westminster stand in for "Westminster, Conn." — Certain Fury is an exercise in contrived squalor. Neither of its stars is likely to be invited to the 1985 Oscar ceremonies.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1985. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: For Certain Fury’s bad girl actress, life would only get worse. At 21, Tatum O’Neal took little pleasure from her film-star fame. In her 2004 autobiography, A Paper Life, she described her father's drug problems, and alleged that his drug dealer had molested her when she was 12. It's been reported that she’s struggled with a drug habit of her own since the age of 14. During her adult years, the tabloid tales told about her — teenaged dates with singer Michael Jackson, a troubled eight-year marriage to tennis star John McEnroe, and a 2015 “affair” with Rosie O'Donnell — became better known than her sporadic film and TV appearances. Earlier this month, Page 1 of the Globe, a supermarket weekly, featured the headline “Tatum O’Neal Locked in Psycho Ward.” It reported that the “allegedly suicidal” actress had been placed on psychiatric hold in a Los Angeles hospital. In all, not a happy memory for O’Neal as she marks her 57th birthday today (November 5).

For Certain Fury’s good girl, her sixth feature-film starring role was more of a bump in the road. A performer whose roots were in New York’s musical theatre, Irene Cara was no Hollywood princess. Her movie breakout came at 17, when director Sam O’Steen cast her in the title role of his feature Sparkle (1976), a musical biography based on the Diana Ross story. Cara went on to star in Alan Parker’s 1980 musical Fame, and collected a best original song Oscar for her collaboration with Giorgio Moroder on Adrian Lyne’s 1983 feature Flashdance. Her talent as a singer-songwriter made it possible for her to continue a performing career that included stage, screen and television appearances while pursuing an eight-year-long lawsuit against her record label for withholding royalties. She won that battle in 1993, but had to endure a period of virtual blacklisting in the recording industry. In 1999, she followed through on a plan “to put together a band of brilliant women.” and formed Hot Caramel. “I consider myself semi-retired, Cara said in a 2018 interview from the beachfront Florida home where “I live off my royalties.”

For Certain Fury’s location crews, life would only get better. Filmed in June 1984, the low-budget American feature was one among many U.S. productions taking advantage of an historic decline in the exchange rate of the Canadian dollar and contributing to the growth of a “Brollywood” in the B.C. rainforest. Today, motion picture and television production is a major part of the provincial economy, with a record $4.1 billion said to have been spent here in 2019. Metro Vancouver continues to be the third-largest hub for the industry in North America (behind Los Angeles and New York City), even during the COVID-19 pandemic.