Wednesday, June 4, 1980

EVER SINCE AMERICAN GRAFFITI, the names Gary Kurtz and George Lucas have been inextricably linked. Lucas was the director, and the creator of the original concept. Not unexpectedly, he received the lion's share of the critical attention.

Kurtz, the film's co-producer, stood out of the spotlight. His role in the project was less glamourous, seemed less involved and was considered less interesting,

American Graffiti (1973) was a milestone movie. Its success made it possible for Lucas to realize his dream project, the sweeping, swashbuckling 1977 space epic called Star Wars.

American Graffiti was the turning point. Its success was due in no small measure to Gary Kurtz. Following delivery of the picture to Universal, Lucas later told an interviewer, Kurtz spent his time "trying to keep them from destroying the film."

Their creative collaboration continued. The Los Angeles-born Kurtz went on to produce both Star Wars (1977) and its current [1980] sequel The Empire Strikes Back.

Throughout, the Force has been with them. The phenomenal popularity of the series has allowed Lucas to indulge his natural shyness and become a virtual recluse.

"George doesn't like to talk to the press," Kurtz, said during a recent visit to Vancouver. Reporters' "inaccuracies" bother him, so Lucas seldom makes himself available for interviews any more.

As a result, the producer has become something of an Aaron to the director's Moses. Kurtz, when he speaks, is the spokesman for Lucas, Lucasfilms and their movies.

In that role, though, Kurtz reveals very little of himself. Like Aaron, he remains a shadowy figure even when standing in the full glare of the spotlight.

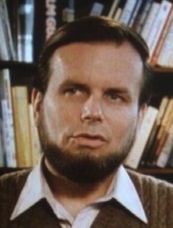

Gary Kurtz, 39, is not a man to display his passions in public. Looking like a church elder in his neatly trimmed captain's beard, he says that the success of the Star Wars pictures notwithstanding, his personal aspirations have not changed.

"I've always been a film fan," he says. "That's why I've worked at so many different jobs. I've always wanted to work in a variety of capacities on a project."

Like Lucas, Kurtz studied cinema arts at the University of Southern California. Like Francis Ford Coppola, who attended film school at nearby UCLA, he knew that the only way to learn movie-making was by making movies.

His "different jobs" include experience as a lab technician, film editor, electrician, soundman, cameraman and production manager. During the making of 1963's The Terror, a Roger Corman project, Kurtz met Coppola.

A few years later, Coppola was producing films out of his own San Francisco studio, American Zoetrope. Kurtz, who was working as associate producer on a picture called Two Lane Blacktop (1971), visited Coppola to discuss the use of some Zoetrope facilities.

At the time, Zoetrope's first feature, the science-fictional drama THX-1138 (1971), was in post-production. Kurtz met writer-director George Lucas and, before long, they were shaping an idea that would become American Graffiti.

Today, both Lucas and Kurtz are multi-millionaires. "We always thought of ourselves as struggling film students fighting the Establishment," Kurtz says. "Suddenly, we are the Establishment,"

Even so, surprisingly little has changed, says Kurtz. "Except, of course, we now have greater access to other people in the Establishment."

"The greatest asset of a successful film is that it buys you the time to work on other things. If you have that — the development time for projects — it changes your attitude.

"It means that you're not worried about earning a basic living, or putting food on the table. That type of security is the most important thing that success gives you."

Though Lucas and Kurtz remain friends and close business associates, their success appears to have underscored some fundamental differences. Lucas has no regrets about giving up the director's chair to manage the larger corporation.

Kurtz, on the other hand, is not interested in becoming "an administrator." He sees himself "going in a different direction," one that has him continuing as a line film-maker.

During production of The Empire Strikes Back (directed not by Lucas, but by Irvin Kershner), Kurtz was on the set almost every day. "Good producers work along with the director," he says. "Their prime function is to isolate (the director) from day-to-day problems, to help make it all work."

Like most big-budget films, The Empire Strikes Back had its share of problems. Principal photography was underway when second-unit director John Barry died.

Since second (or action) unit material was being shot at the same time as first (or dramatic) unit scenes, Kurtz stepped in and directed in Barry's stead. He plans to continue directing.

Although he will remain involved with Lucasfilms "as a consultant," Kurtz is developing a pair of new projects on his own. One is a musical comedy written and directed by satirist Stan Freberg. Kurtz will produce.

The other, a period drama set in the early 20th century, is designed as Kurtz's own feature-film directing debut. Based on a novel, "it is currently being developed as a screenplay by an English writer." He refuses to reveal more.

"Security," he says, "allows you to take chances."

If Kurtz feels excitement, anticipation or enthusiasm, he hides it well. For the moment, he's content being an aloof, corporate spokesman for The Force.

Keeping his distance is the man who helped created the greatest popular success in film history. Hidden away is a man who "set out to make movies," and who promises to make more.

The above is a restored version of a Province interview by Michael Walsh originally published in 1980. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: The "inextricably linked" Lucas and Kurtz had in fact parted company at the time of our interview. The older of the two by four years, Kurtz had his own company (called Kinetographics), and his own ideas about how movies should be made. Having taken up residence in London during the production of The Empire Strikes Back, he stayed on, making Britain his home base. Although neither of the projects he mentioned in our 1980 conversation came to fruition, he did go on to work with Jim Henson, as producer and second-unit director on the Muppet master's 1982 fantasy The Dark Crystal. He then took on the role of executive producer for Walter Murch, director of the imaginative live-action fantasy Return to Oz (1985). Though both were quality features, they failed to create the box-office magic of the Star Wars series, and Kurtz's career suffered as a result. Returning to science fiction, he produced a 1989 post-apocalypse film written and directed by Tron creator Steven Lisberger called Slipstream. Though it starred Mark Hamill, the British-made movie was a financial disaster in the U.K., and has never been released theatrically in North America. Little heard from since, Kurtz produced a released-in-Britain-only comedy thriller, The Steal, in 1995, and an animated Christian television series for children called Friends and Heroes (2007).