Tuesday, May 8, 1978.

F.I.S.T. Written by Joe Eszterhas and Sylvester Stallone. Music by Bill Conti. Produced and directed by Norman Jewison. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: some vIolence.

IN 1961, BUDD SCHULBERG met with Robert F. Kennedy, then Attorney General of the United States. The subject of their conversation was the 1960 book, The Enemy Within, Kennedy's personal account of his service with the Senate Select Committee that investigated corruption in Jimmy Hoffa's Teamsters Union during the late 1950s.

Kennedy had been impressed with Schulberg's hard-hitting On the Waterfront (1954) screenplay. He was willing to let the Oscar-winning writer adapt his book for the movies. After their meeting, Schulberg went at it with a will, completing the job some 15 months later.

It was never filmed. On the death of producer Jerry Wald, the project was shelved. By all accounts, though, Schulberg's story was similar to the the tale told in F.I.S.T.

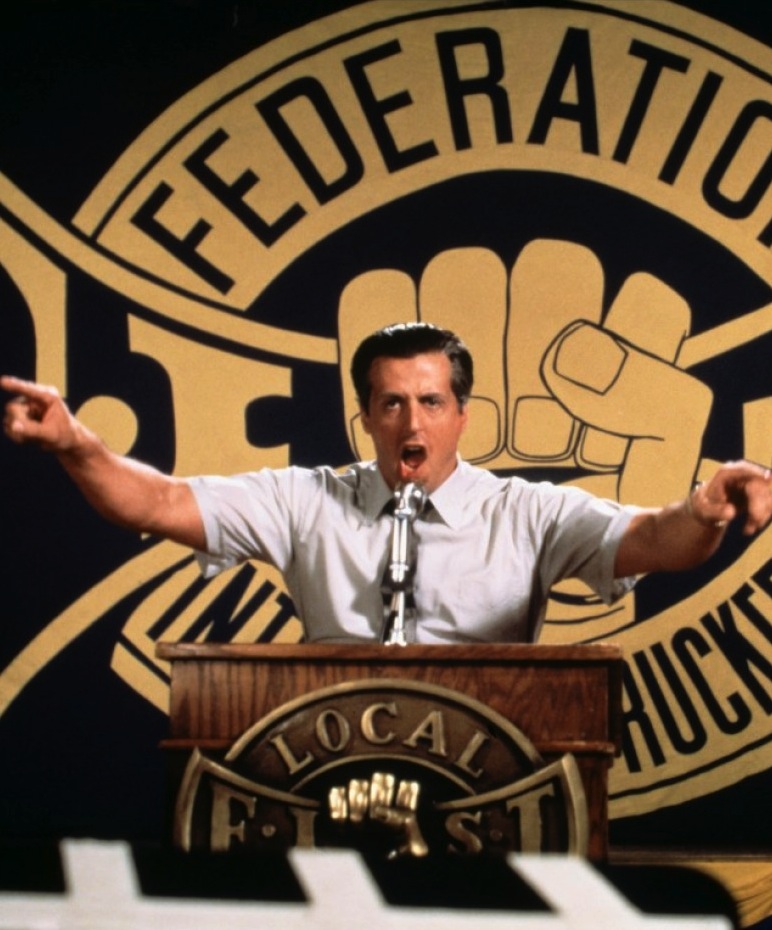

F.I.S.T. is producer/director Norman Jewison's dynamic attempt to cross 1949's All the King's Men with The Godfather (1972). It chronicles the rise of a union demagogue who closely resembles the ill-fated James R. Hoffa.

Young Johnny Kovak (Sylvester Stallone) is a Cleveland warehouseman, circa 1938. Fired from his job on the loading dock, he signs on with the Federation of Interstate Truckers (F.I.S.T.) as an organizer.

A naturally charismatic figure, Kovak builds the local's membership to the point where it is able to demand a contract from the biggest shipper in the city. A long and bitter strike follows, one that becomes violent when the company calls in "the law and order league," an armed goon squad that leads a murderous attack on the peaceful picketers.

Kovak responds by calling in Vincent Doyle (Kevin Conway), a boyhood buddy who has become a local crimelord. Much to the horror of Kovak's friend and lieutenant, honest Abe Belkin (David Huffman), Doyle firebombs the company's operations to a standstill.

Kovak wins his contract, and the union is on its way.

Jewison, a director with a talent for making hugely entertaining films, went into the F.I.S.T. project with two creative strikes against him. One was the Stallone-Joe Eszterhas script, an uninspired screenplay that ranges from the barely adequate to the downright punchy.

"I don't know how you feel about unions," F.I.S.T. local president Mike Monahan (Richard Herd) tells the newly unemployed Kovak, "but I saw you at Andrews," — wait for this — "You got a way with men."

(Praise God for small mercies. Later, when Rod Steiger turns up as racket-busting Senator Madison, Stallone does not tell him "I could'a been a contender!")

The second strike is Stallone's performance. John Kovak is a tough and demanding role, one that requires an actor to convey a sense of shrewd, instinctive intelligence. Stallone, despite his heavy-duty personal p.r., was not the man for the job.

As written, Kovak combines the easy wit of a Paul Newman with the icy introspection of an Al Pacino. As played, he comes across as an arrogant variation on Stallone's Rocky.

On the plus side, Jewison is a master of visual mood. Robbed of the opportunity to make a true epic — Roots for organized labour — he still turns out a vigorous, involving entertainment. His handling of the F.IS.T. local's first strike is so effective that audiences are actually cheering at the outcome.

Ultimately, though, F.I.S.T. is a tragedy. For Kovak, it's the old story of power and corruption. For Jewison, the sad story of a director who has built his movie around a hot star with only lukewarm talent.

* * *

CONTI-BLAST: Last week [May, 1972], in a review of An Unmarried Woman, I suggested that composer Bill Conti's score worked against director Paul Mazursky's picture.Credit Norman (Jesus Christ Superstar) Jewison with having a better musical ear than Mazursky, and Conti for responding to his director's good taste. Conti's F.IS.T. score is absolutely superb.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1978. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: In his 2004 autobiography This Terrible Business Has Been Good to Me, Toronto-born Norman Jewison tells us that "F.I.S.T. is a story about the betrayal of the American labor movement." It was a story he had to fight to make because, in the words of studio executive Arthur Krim, "'no one is interested in the labor movement'." Jewison's experience reflects Hollywood's historic ambivalence about the subject. From the beginning, artists have attempted to celebrate the humanity embodied in collective action against perceived injustice. Films about working class organization were a staple of early silent cinema. With the rise of Hollywood, filmmaking became an industrial activity, and the moguls had little sympathy with the bargaining process. The self-important Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences was founded (in 1927) not to hand out awards, but to prevent the formation of trade unions within the studios. Labour-friendly directors, such as Frank Capra, Martin Ritt, John Sayles and Jewison, were outnumbered by socially indifferent or downright hostile creators like Elia Kazan. Today, the ones who lack interest in the subject inhabit the corporate head offices of the media conglomerates, and they answer to the One Percenters. In the case of F.I.S.T., Jewison goes on to tell us, the movie got made because he was able to cast the studio's choice of star, the post-Rocky Sylvester Stallone. It also fit the preferred Hollywood narrative that equates union leaders with corruption and mob links.

See also: Other Norman Jewison features that I've reviewed are: Gaily Gaily (1969), Jesus Christ Superstar (1973), and Rollerball (1965) You might also enjoy reading about director Martin Ritt's 1979 union organization drama Norma Rae.